A Magical Moment In The

World Of Art-The Recent “Discovery” Of 26 Painting Presumed Destroyed In The

Nazi” Night Of The Long Knives Destruction Of ‘Degenerate Art’ ” Of Abstract

Impressionist Raybolt Drexel Shakes The Rafters

By Laura Perkins

The reader may pardon me

for having “gone dark” for the past few months and thus having avoided getting immersed

in my fellow writer (and sometimes art mentor) Sam Lowell’s on-going battle,

shadow boxing really, about the fate of the masterpieces that were stolen in

the heist of the century (20th) at the Isabella Stewart Gardner

Museum in Boston some thirty years ago. Sam’s main beef, no, point, no, admiration,

having been nothing but a charter member corner boy in his desperately poor

youth so always on the lookout for the easy score and always just a little East

of Eden on the legality question, was how easy the heist had been. Certainly to

his eyes and ears with plenty of inside help and he didn’t mean the silly

rent-a-cops who were supposed to protect the crown jewels but probably some

well-positioned curators and volunteer tour guides. You know the cubby hole

knowledge of some exotic artist for which some well-placed curators have written

a seamless 66 page essay on as part of some exhibition and the suburban matrons

who thrill to jabber their six-sentence knowledge of say, well, Rembrandt since

we are rightly commemorating his 350th birthday of later rating. Or

as likely among those “volunteer” art students from the Museum School and Mass

Art who facing the prospect of garret life for the next few decades decided to find

a benefactor like the old artists, like Rembrandt if I am not mistaken did in

the courts and chanceries of Europe back in the day. If the reader will recall

at least one curator, a Holbein the Younger expert and a couple of art students

(not sure from which school) left the staff shortly after the theft never to be

heard from again after a light FBI grilling. But enough of this for Sam and I

have gone on endlessly about the insiders as well as the simply although beautiful

plan as it was laid out.

More importantly than who

qualified as prime suspects for the job on the inside for the actual thefts

though, the thirty-year question really, was how the various agencies investigating

the whereabouts of the stuff have come up mainly with egg on their faces. Sam,

even today has a certain amount of glee when he describes the lightweight work

done by the FBI and Boston Police to

recover the masterpieces even with the so-called big rewards available (although

really chump change compared to the value of the art today at half a billion

maybe more today so you know that missing curator and those so-called art

students are not giving up squat, Sam’s word, not playing ball with the law,

also Sam’s, else find themselves in stir. What a laugh.)

Frankly, Sam, and through

Sam, me have had a few so-called theories about the fate of the works, where

they are, who had them and who has them now. It did not take old Seth Garth

long to figure out where such stuff would be in the Greater Boston area once He

and Sam put their heads together. So it was no surprise, made perfect sense to

me to have known that the works had been stored in the Edward McCormick

Bathhouse, or really the shed where they keep the tools and trucks, over on Carson Beach for years so Whitey

Bulger, complete with pink wig and paper bag beer could eye them at his

pleasure while he was on the run. The key link was one guy, a career criminal

mostly but with a François Villon poetic heart, who claimed to be the President

of Rock and Roll, Myles Connors, who did the detail work (and also did as far

as we know some very good preservation work to keep the “Big 13” from the

elements coming off of Dorchester Bay.

Probably had things worked

out Whitey’s way the artworks would still be over in the bathhouse, still be a

one-man museum exhibition. But all of that art for art’s sake that a painter

named James McNeil Abbot Whistler laid on an unsuspecting world went in the

trash barrel because once Whitey needed dough for his defense in a fistful of

murder and mayhem charges he sold all the good stuff, sold everything I believe

except those hazy sketches nobody would really want today except museum

curators desperate to fill up their artist retrospectives with enough material to

not leave any empty spaces. Sold the lot minus the loss-leaders to a guy, I

think his name is Tom Steyers, something like that, a hedge fund guy who has

some social consciousness, who has the good

stuff locked up somewhere in order to peep at them on occasion but mainly to

leave his kids with some start-up dough if they too wanted to be socially conscious

billionaires. The second-rate stuff for all I know may still be in the bathhouse

garage but don’t quote me on that.

Frankly though, especially

now that Whitey has taken the fall, has gone to sleep with the fishes, that is

all old news, speculation and macho guy talk like Sam and Seth get into when they

need some hot air time and not worthy of my time. Not worthy of my time as an acknowledged

and proud amateur art critic. Not against the part I played in helping to put together

the clues that would get 26 works, no, masterworks by the famous Abstract

Impressionist Raybolt Drexel which everybody though the Nazis had destroyed

when they went on a rampage against “degenerate art,” decided to burn everything

in sight that blighted their vision of an Aryan Garden of Eden back in the 1930s

when they thought they had a thousand year Reich in front of them. I played a minor

role in the investigation and research but I played a part recognized by those inside

the art cabal, even by my usual nemesis Clarence Dewar, professional art critic

for Art Today. Believe me that kudo says plenty.

A little background, my

background into the case is in order to set the scene. Back when I was a

college student, back in the 1960s, at Rochester I was always mesmerized by a

painting that hung near the statue of the great black abolitionist Frederick

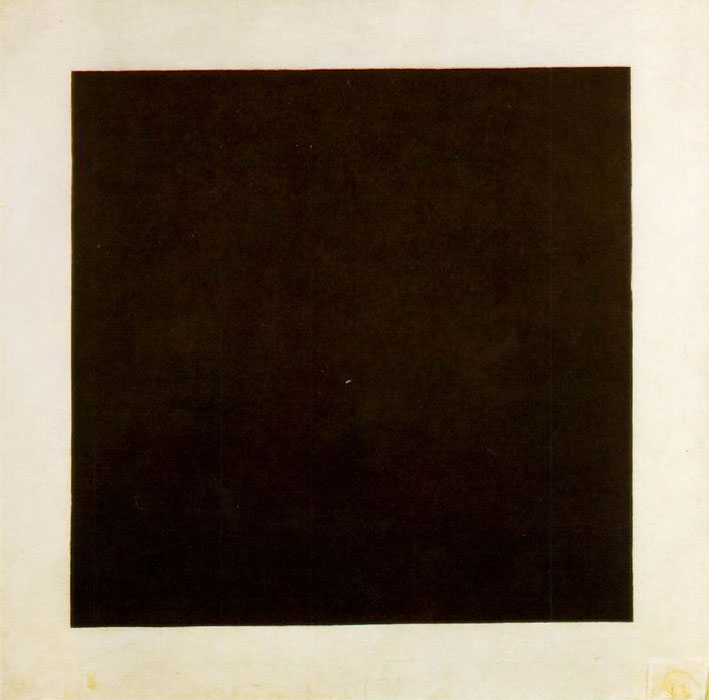

Douglass simple entitled Steel #6 by Raybolt Drexel. The amazing thing, no, the

two amazing things about this painting, were, one, that it was one of only

three known Drexels to have survived the Nazi onslaught in the 1930s when these

scum were burning everything in sight by guys like Max Beckmann, George Groz,

Milos Drebs and Raybolt Drexel as “degenerate art,” as against the cult of the

superman Aryan race noise that soon enough, well, maybe not soon enough, got bloodied

by some guys from America and Russia who didn’t like their drift of a thousand

years of darkness. The other, number two, was that this painting was an almost classically

pure example of one of the “new wave” trends in early 20th century

art, abstract impressionism, which Drexel did a huge amount to pioneer before

they, and you know who the “they” is and if you don’t think Nazi scum, grabbed

him and did something vile to him which even today we don’t know exactly what it

was and where he was buried except somewhere

in Poland on the way to the concentration camps.

I was at Rochester for

four years before heading to the “real world” but I would bet that I looked

that that painting a hundred times, at least. The funny thing is that it always

struck me in different ways when I saw it in various lights, times of days, and

my own personal moods. That is what abstract impressionism was about, that is

what we know Drexel was trying to do with his paintings in a world moving

toward various forms of expressionism and then pure abstraction (which usually

today leaves me hollow). That is what he detailed in the few writings he was

able to sneak out of Germany before they grabbed him. Here’s the play on Steel

#6; numerous layers (one curator, an abstract impressionist expect so I will

go with her judgement, estimated at least twenty) of white in all its variations

covering most of the 48” by 72” canvass frame. Then in the lower left corner

maybe 12” by 18” a piece of steel. Or something that looks like steel in all

its admixtures of straight-up gray, blue-gray, black-gray, green-gray,

charcoal-gray, lemon-etched gray and so on. The amazing point though, the look

at it one hundred plus times point during four years at Rochester point, was

the essence of the piece, that is the best way I can say it, if not exactly explain

it, took one from the original iron ore to the finished product in one fell

swoop. Incredible, magnificent, amazing.

Back to the main story

though. Not all the details of how these glorious 26 paintings survived are

known even though we pressed the issue as far as we could, talked to everybody

in Germany (mostly though second-hand conversations since the generation who would

have known the facts straight up had passed on or had been killed during the

war) who had any information about the transit, including army officers and lower-level

government officials. For, example, some tank commander’s son, his father after

the war proud to say he had saved some great art whatever he did in the war heading

with his division west along the transit route, would tell us how the “shipment,”

cloaked as an “ironic” steel shipment for the front stopped in the Ruhr Valley

on the way and that the old man had ordered four trusted NCO guards to insure

its safety. Many such examples.

In the great scheme though,

what had originally saved the Drexels from the faggot fires of Nuremburg and Berlin

was that after Drexel was grabbed what appears to have happened is that some

half- committed Nazi named Klein who had a love of art (as we have seen plenty

of autocrats and cravens who would blow up the world still keep some art work

in their bunkers with them so don’t be so surprised by that love business) decided

that the good German name of Drexel could not produce “degenerate art.” Meaning

as well as other things that a non-Jewish German could not produce such art

although that did not stop Herr Klein from having his SS boys grab Drexel for

the rails to Poland while taking the 26 (it may have been 29 there is

speculation 3 pieces got lost or destroyed on the way west) masterworks. The “other things” being that it would be

quite a stretch to see the simple designs of Drexel’s work on the same plane as

say Max Beckmann who really did try to rub noses in his productions.

The three previously known

to survive Drexels had been brought to America by George Groz who consigned

them to the New World Gallery in New York City where Allan Austin, a rich

Rochester alum saw Steel#6 and decided to purchase it for Spring Hall as a

fitting tribute to economic progress which

fit in with the mission of the college). Once the European war started this

half-Nazi, apparently still half-Nazi if his rise to general meant anything decided

to take the artworks west with him while the Nazi tide was rising. West to

Paris where he was stationed apparently through most of the war. When things

started to go south for Germany after the heroic Soviet struggle at Stalingrad

this Klein made plans to get the paintings to America. Some Germans, including high

level German officers like Klein when they began to see the writing on the wall

were going to save their asses as best they could when the Americans came knocking

at the doors. Unlike guys like Martin Blatner and Max Steiner who went down in

the bunkers to fall down with the 1000-year Reich. Through some byzantine network,

the “tunnel” I have heard it called, got the stuff out of Europe and into the

mansion of Amos Drexel in Pennsylvania-without him or his staff being aware of

what would wind up in the basement as an ordinary shipment of industrial goods.

This wealthy industrialist had some family relationship with Raybolt’s and thus

a perfect set-up for a delivery drop.

The story stops there for

a while for the simple reason that Herr Klein never made it out via the OSS “tunnel”

which maybe tells you how bad a character he was, how dirty his hands were what

with the death of Drexel and who knows how many before he hit Paris and grabbed

every Resistance fighter he could get his hands on, hung then on lampposts up

and down the Seine as cautionary tales. Although I found no listing for him in

the Nuremburg tribunals, even in the secondary lists since the Dulles boys were

grabbing whoever did not stink to high heaven in order to begin in earnest the

fight against the emerging Soviet power in Europe he must have been put to

sleep.

The story from my ends

begins a few years ago when I read an article in a scholarly journal which referenced

how methodical the Nazis were before they went on the run, say 1944 when even

Max Steiner know the game was up and decided to hit the bunker early. For

example, for our present example, some low-level clerk or something was in

charge of, made a list of all the “degenerate art” which went to the pyres in their

crazy lust to rid the world of most 20th century art. That made me

curious about the fate of the other art works of Drexel which never made it to

American shores. Through various connections I was able to get the list of destroyed

art. I could not stop my heart from serious fluttering when I saw that nothing

of Drexel’s was officially listed as consigned to the flames. That would

eventually, again due to that great German skill of organizing everything into

workable systems, open up the trail of who last had access to the Drexel work

and then to Herr Klein’s role. (It was well known that Klein had had Drexel in

his clutches in the 1930s before he “disappeared “ attested to by half a dozen SS

scum who were only too glad to speak of their role of cleansing Germany of modern

filth.)

The hardest part turned

out to be in Pennsylvania, although not in the way one would think. Working

with a senior curator from the Met, the gal who claimed that Steel#6 had twenty

layers of white on canvass before anything else was done to the surface and a

Drexel expert, we worked our way to pay dirt. Along the way interviewing some

relatives of an art dealer in Paris who had worked with Herr Klein to get the

works out of the country before all hell broke loose I had been given information

that the clandestine works had been sent to something called the Drexel

Institute which would have made sense, but which subsequent to 1970 I think changed

to the more generic Drexel University. We spent untold weeks checking out possible

lead there, nada, nothing. Then somebody told us about the Drexel mansion about

ten miles outside of Philadelphia. A few weeks work there going through many

crated boxes and crates looking for something that would have disclosed the

item had come through Paris as least we found the secured iron box filled with

the treasures, none on frames but after many years still in good shape (that

estimation from the Met curator who also helped with the question of authentication).

A book is being written

about this extraordinary find, a book which I will be involved with having

published by Art Press, so I have limited myself to the shell of the way the

items were finally discovered which were actually worthy of a detective novel.

What intrigued me, what frankly freaked me out was that the Steel#6 up in

Rochester was the end-piece of a series of six paintings on the same general

theme of birth and growth. So in Steel#1-5 you will see the same attention to

massive layering as in #6 although fewer layers but as you put the framed works

in a row (Drexel noted in pencil that this is the way they should be collectively

hung on the back of #1) you start with a very small gray object and work your

way up to what I have previously described in viewing Steel#6. Amazing,

beautiful and perhaps the definitive work expressing what abstract impressionism

was all about when it flowered alongside Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism, Abstract

Expressionism and pure abstraction.

No comments:

Post a Comment