From The Labor History Archives -In

The 80th Anniversary Year Of The Great San Francisco, Minneapolis

And Toledo General Strikes- Lessons In The History Of Class Struggle

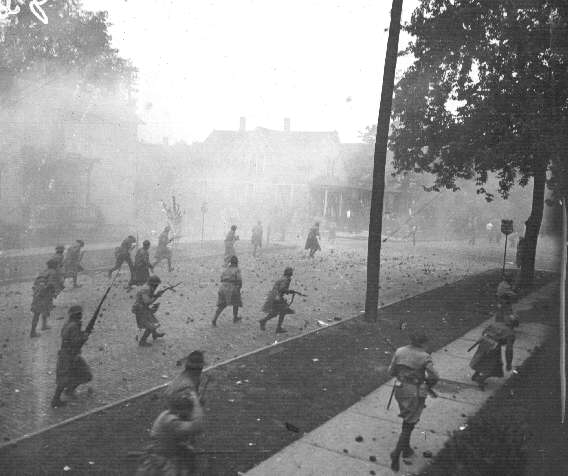

The Toledo Auto-Lite strike, 1934 - Jeremy Brecher

From The Archives Of The Socialist

Workers Party (America)- Some Lessons of the Toledo Strike

Frank Jackman comment:

Marxism, no less than other

political traditions, and perhaps more than most, places great emphasis on

roots, the building blocks of current society and its political organizations.

Nowhere is the notion of roots more prevalent in the Marxist movement that in

the tracing of organizational and political links back to the founders, Karl

Marx and Friedrich Engels, the Communist Manifesto, and the Communist League. A

recent example of that linkage in this space was when I argued in this space

that, for those who stand in the Trotskyist tradition, one must examine closely

the fate of Marx’s First International, the generic socialist Second

International, Lenin and Trotsky’s Bolshevik Revolution-inspired Communist

International, and Trotsky’s revolutionary successor, the Fourth International

before one looks elsewhere for a centralized international working class

organization that codifies the principle –“workers of the world unite.”

On the national terrain in the

Trotskyist movement, and here I am speaking of America where the Marxist roots

are much more attenuated than elsewhere, we look to Daniel DeLeon’s Socialist

Labor League, Deb’s Socialist Party( mainly its left-wing, not its socialism

for dentists wing), the Wobblies (IWW, Industrial Workers Of The World), the

early Bolshevik-influenced Communist Party and the various formations that made

up the organization under review, the James P. Cannon-led Socialist Workers

Party, the section that Leon Trotsky’s relied on most while he was alive.

Beyond that there are several directions to go in but these are the bedrock of

revolutionary Marxist continuity, at least through the 1960s. If I am asked,

and I have been, this is the material that I suggest young militants should

start of studying to learn about our common political forbears. And that

premise underlines the point of the entries that will posted under this

headline in further exploration of the early days, “the dog days” of the

Socialist Workers Party.

Note: I can just now almost hear some very nice and proper

socialists (descendants of those socialism for dentist-types) just now,

screaming in the night, yelling what about Max Shachtman (and, I presume, his

henchman, Albert Glotzer, as well) and his various organizational formations

starting with the Workers party when he split from the Socialist Workers Party

in 1940? Well, what about old Max and his “third camp” tradition? I said the

Trotskyist tradition not the State Department socialist tradition. If you want

to trace Marxist continuity that way, go to it. That, in any case, is not my

sense of continuity, although old Max knew how to “speak” Marxism early in his

career under Jim Cannon’s prodding. Moreover at the name Max Shachtman I can

hear some moaning, some serious moaning about blackguards and turncoats, from

the revolutionary pantheon by Messrs. Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky. I rest

my case.

********************

No comments:

Post a Comment