“Workers of The World Unite, You Have Nothing To Lose But Your Chains”-The Struggle For Trotsky's Fourth (Communist) International-From The Archives-Founding Conference of the Fourth International-1938

<4> This article was first published in the August 1944 issue of Fourth International. [Jean van Heijenoort (1912-1986) was Trotsky's secretary in 1932 in Prinkipo, and followed him to France, Norway and Mexico. As a leader of the Fourth International he headed a provisional international centre in the United States during World War Two and left politics shortly thereafter.]

The October revolution established the first Workers' State but remained isolated. "Without revolution in Europe," said Lenin repeatedly "we shall perish." History verified the truth of his words but in its own manner. Degeneration appeared in the apparatus itself of the new regime—the party that led the revolution to victory.

The leaders of the two official workers' parties vied with each other in their impotence in the face of the fascist menace. The Social democratic leadership desperately grasped at a democracy which, in the midst of economic chaos and the sharpened social and political conflicts, was disowning itself. The Stalinists acted in line with the "genial" theory of their leader, that it was necessary to crush the Social Democrats before fighting fascism. They had made common cause with the Nazis in the famous plebiscite in Prussia in August 1931. When the fascist menace became imminent, they clamored with braggadocio: "After them will be our turn!"

A few voices raised the question: haven't we waited too long? Shouldn't we have recognized the need of a new International much sooner? To this Trotsky answered: "This is a question we may well leave to the historians." He was undoubtedly profoundly convinced that the change in the policy would have been incorrect several years sooner, but he refused to discuss this question because it was no longer of practical and immediate interest.

This space is dedicated to the proposition that we need to know the history of the struggles on the left and of earlier progressive movements here and world-wide. If we can learn from the mistakes made in the past (as well as what went right) we can move forward in the future to create a more just and equitable society. We will be reviewing books, CDs, and movies we believe everyone needs to read, hear and look at as well as making commentary from time to time. Greg Green, site manager

Friday, September 19, 2014

As The 100th

Anniversary Of The First Year Of World War I (Remember The War To End All Wars)

Continues ... Some Remembrances-Poet’s Corner-German Poets

German War Poetry

|

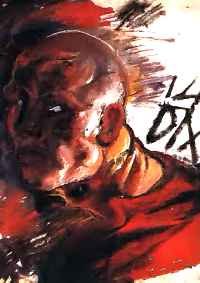

| Self-portrait as a Soldier of 1914 by Otto Dix |

| Here's some German war poetry in German. These are not the verse of polished poets, that is to say "poets turned soldiers", these poems are the work of front line soldiers, "soldiers turned poets". There's quite a difference between the two art forms. These poems were the soldier's way of coping by expressing their feelings about such topics as fallen comrades and the homeland, which in once sense was so close, but in another, was a million miles away. They may be considered rough by some and lacking in form or content by others, but they do manage to capture the everyday thoughts of the soldier and the mood of the trenches. If anyone out there is more comfortable in their mastery of the German language than I am and would like to translate any of these works, I would be more than happy to create an English language version of this page. |

|

***The

Spear Of The Nation-Nelson Mandela: Long Walk

To Freedom

DVD

Review

From

The Pen Of Frank Jackman

Nandela: Long Walk To Freedom, Idris Elba, Naomie Harris, 2013

No

question after the black civil rights struggle here in America, headed at various

points by Doctor Martin Luther King, subsided with some partial victories

around voting and freeing work opportunities the axis of the international

black liberation struggle shifted, shifted in American eyes, to the horrible

conditions of blacks in South Africa. There under the conscious apartheid policy

complete with the hated pass system of the Afrikaner government blacks were

held as little more than chattel. And were expected to like it to boot.

Something about the white man’s “civilizing mission” although more likely, much

more likely his craving for cheap labor to work those money-filled,

resource-filled mines that drove the South African economy. The situation

called for black resistance, called big time for black resistance, since the

white government was not interested in the least in sharing power, any power,

except maybe that given to their black front men to control the masses. Enter

the African National Congress (ANC), or actually the arrival through fits and

starts of lawyer Nelson Mandela into the ANC and you have a leader who the

world came to know as the icon of that organization. And this film, Nelson Mandela: A Long Walk To Freedom

based on his 1995 autobiography and which opened late in 2013 as he passed away

traces the evolution of the man from a free-lancer lawyer to a serious

anti-apartheid revolutionary leader.

Of

course any political liberation movement, the black civil rights movement here

in America with its bookends of Doctor King calling for non-violent resistance

to the oppressor for the redress of grievance and Malcolm X calling for “by any

means necessary or the freedom struggle in the early days in the ANC with it

non-violent resistance policy and after Sharpsville with armed resistance, has

to deal with how it will conduct the struggle. Nelson Mandela (played in a very

strong performance by Idris Elba) as shown graphically in the film as the

repression worsened helped move the ANC from one policy to the other as the circumstances dictated and paid the price.

That price being the incarceration along with the central leadership of the ANC

on desolate Robbins Island for over twenty-five year.

Now

in this country we are no strangers to the plight political prisoners,

particularly back in the 1960s and the heyday of the Black Panthers some who

are still languishing relative obscurity in American prisons. And that has been

the fate of any number of political prisoners over the years in many countries.

The different in South Africa was that Nelson Mandela and the struggle for his

freedom was made a continual international campaign. And in a sense as the film

also shows there was no more tireless freedom fighter in her own right for

Nelson’s freedom than his second wife, Winnie (played by Naomie Harris).

Obviously the love story, the long term deprived of love one story, is a good

cinematic hook to tell the story. Tell the story of a personally-driven

struggle to get her man back at first. Then as the years passed and new

generations were coming to the struggle with more in-your-face ideas about how

to bring down the regime how Winnie moved politically to Nelson’s left on the need

to do that (as well as growing personal estrangement). That shift in the

struggle as exemplified by the Soweto uprising in the mid-1970s did not get

enough attention in the film since Nelson was removed from what was going on. That

too is the plight of the political prisoner isolated as new possibilities

emerge and constituted a strong reason to get him out of jail-fast.

Since

we all know that in the end, after all hell broke loose in the early 1990s,

that South Africa shifted from white to black-centered rule and Nelson Mandela

became the first black president. What is interesting in the last part of the

film before he became president is the personal and organizational struggles

he, Winnie, and the leadership of the ANC went through to get the white

government under de Klerk to see the writing on the wall. No question Mandela

was significantly to the right of Winnie (along with other younger fighters)

and her “make the townships ungovernable” policy with his sense that blacks

could not win a civil war against a determined army and to offer up what, in

effect, was a race-neutral black- led government. He may have been right at

that time but the evolution of the struggle in South Africa since then with

plenty of tough times for the black population and whites still in effective

control of the economy makes me wonder.

***In The Time Of The Hard Motorcycle Boys- In Search Of History: Hell’s Angels

DVD Review

From The Pen Of Frank Jackman

In Search Of History: Hell’s Angels, starring, well, the

various generations of Hell’s Angels since 1948, 2006

Several years ago when I was trying to finally reconcile myself

with the hard upbringing I had had in my old working-class town of North Adamsville

south of Boston I mentioned to some new friends that in high school in the early

1960s I had been drawn to and repulsed by the hard ass motorcycle guys from

Boston who roamed at will through the streets of our town to get to Adamsville

Beach. The beach a local rendezvous for bikers, babes, and watching “submarine

races” after midnight. Not all of those together and maybe none together

depending on who was down there any given night. Who meaning what young women,

and what kind were drawn to that locale when those guys with their chrome-infested

bikes came to a stop. The drawn to part of the motorcycle guys for me was that they

were “cool,” outlaw guys with those big motorcycles blazing and I fancied myself

a rebel. The repulsed part was that they would trash the beach, would pick on regular

guys to try to “make” their dates (and hassle those dates too with ugly

language and gestures which appalled most of them), and thought nothing of beating

up guys for just looking the wrong way at them. In the end I feared them more

than saw them as heroic figures, but that was a close thing. All of these points

kind of encapsulates the subject of the In

Search of History documentary about the most famous outlaw motorcycle club

around, the post-World War II West Coast-born Hell’s Angels.

Needless to say after watching this

exploration of the roots, the behavior, the legend, and the meaning of the Hell’s

Angels as a sub-culture that was not the end, but rather the beginning of

thinking through the great American night bike experience. And, of course, for

this writer that meant going to the books, the films and the memory bank to

find every seemingly relevant “biker” experience. Such classic motorcycle sagas

as “gonzo” journalist, Doctor Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels and

other, later Rolling Stone magazine printed “biker” stories and Tom

Wolfe’ Hell Angel’s-sketched Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (and other

articles about California subset youth culture that drove Wolfe’s work in the

old days). And to the hellish Rolling Stones (band) Hell’s Angels “policed”

Altamont concert in 1969. And, as fate would have it, with the passing of

actor/director Dennis Hooper, the 1960s classic biker/freedom/ seeking the

great American night film, Easy Rider. And from Easy Rider to the

“max daddy” of them all, tight-jeaned, thick leather-belted, tee-shirted,

engineer-booted, leather-jacketed, taxi-driver-capped (hey, that’s what it

reminds me of), side-burned, chain-linked wielding, hard-living, alienated, but

in the end really just misunderstood, Johnny, aka, Marlon Brando, in The

Wild One.

This documentary touches all those

bases and as usual with an In Search of

History production is filled with “talking head” commentators from definitive

long-time Angels’ leader, Sonny Barger, the above mentioned Hunter Thompson the

most credible writer on the subject, various law enforcement types and sociologist

to place the Angels in the cultural context. Plus plenty of good photographs

and film clips taken at the time to move the fifty-minute sketch along.

Made with Xara

Made with Xara  © Boston International Day of Peace

© Boston International Day of Peace  Join Us on the Boston Common 2 PM to 4 PM

Join Us on the Boston Common 2 PM to 4 PM

For a Day of Music, Dancing, Art & Peace Education Mothers For Justice and Equality

For a Day of Music, Dancing, Art & Peace Education Mothers For Justice and Equality

MJE is a movement that will be sustained for as long as it takes and serves as a reminder to all of us that peace rather than violence is the answer. Mothers for Justice and Equality will lead us to that promised land." --Charles J. Ogletree, Jr, Harvard Law School Professor

MJE is a movement that will be sustained for as long as it takes and serves as a reminder to all of us that peace rather than violence is the answer. Mothers for Justice and Equality will lead us to that promised land." --Charles J. Ogletree, Jr, Harvard Law School Professor  Boston Common September 21, 2014 2:00 PM to 4:00 PM Learn what you can do to help bring peace to Boston and the surrounding communities. Only You Can Bring the Peace

Boston Common September 21, 2014 2:00 PM to 4:00 PM Learn what you can do to help bring peace to Boston and the surrounding communities. Only You Can Bring the Peace

Massachusetts Peace Action is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization working to develop the sustained political power to foster a more just and peaceful U.S. foreign policy.

Massachusetts Peace Action is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization working to develop the sustained political power to foster a more just and peaceful U.S. foreign policy.  Cooperative Metropolitan Ministries founded in 1966, by faith communities to address poverty, housing, and racial justice. Our mission is "to mobilize congregations and communities across economic, religious, racial, and ethnic boundaries so that, in partnership, we can work more effectively for a just society."

Cooperative Metropolitan Ministries founded in 1966, by faith communities to address poverty, housing, and racial justice. Our mission is "to mobilize congregations and communities across economic, religious, racial, and ethnic boundaries so that, in partnership, we can work more effectively for a just society."  The mission of Our Prison Neighbors is to recruit, support and expand the role of volunteers in Massachusetts prisons. We seek to deepen the understanding that we are all part of the same community. In addition, we seek to be a voice to all about the power of this work and the great need for it.

The mission of Our Prison Neighbors is to recruit, support and expand the role of volunteers in Massachusetts prisons. We seek to deepen the understanding that we are all part of the same community. In addition, we seek to be a voice to all about the power of this work and the great need for it.  The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom was founded in 1915. WILPF works on issues of peace, human rights and disarmament at the local, national and international levels. The vision of the Boston Branch of WILPF is to be a positive, visible community working with allies to create peace and justice locally and in the world.

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom was founded in 1915. WILPF works on issues of peace, human rights and disarmament at the local, national and international levels. The vision of the Boston Branch of WILPF is to be a positive, visible community working with allies to create peace and justice locally and in the world.  Friends Meeting at Cambridge We believe that every person is loved by the Divine Spirit. There are Quakers of all ages, religious backgrounds, races, education, sexual orientations, gender identities, abilities, and classes. You are welcome to join us as you are. –Friends General Conference Newcomer Card Violence knows no class, racial, economic or geographical boundaries. People in the US have twice the chance of being murdered than in many other Western countries. Our schools have resorted to metal detectors. Violence in the home, physical and mental, directed against both spouse and child is rampant. Violence knows no class, racial, economic or geographical boundaries. People in the US have twice the chance of being murdered than in many other Western countries. Our schools have resorted to metal detectors. Violence in the home, physical and mental, directed against both spouse and child is rampant.

Friends Meeting at Cambridge We believe that every person is loved by the Divine Spirit. There are Quakers of all ages, religious backgrounds, races, education, sexual orientations, gender identities, abilities, and classes. You are welcome to join us as you are. –Friends General Conference Newcomer Card Violence knows no class, racial, economic or geographical boundaries. People in the US have twice the chance of being murdered than in many other Western countries. Our schools have resorted to metal detectors. Violence in the home, physical and mental, directed against both spouse and child is rampant. Violence knows no class, racial, economic or geographical boundaries. People in the US have twice the chance of being murdered than in many other Western countries. Our schools have resorted to metal detectors. Violence in the home, physical and mental, directed against both spouse and child is rampant.

At St. Paul AME Church, God has empowered and equipped us to develop a variety of ministries. These ministries are designed to address the spiritual, intellectual, physical, emotional and social needs of all people by spreading Christ's liberating gospel through word and deed. Our ministerial efforts extend beyond our local church, community and country; we strive to truly be a Church that speaks to the world. It is our prayer that you accept this invitation and visit St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and that God richly blesses you.

At St. Paul AME Church, God has empowered and equipped us to develop a variety of ministries. These ministries are designed to address the spiritual, intellectual, physical, emotional and social needs of all people by spreading Christ's liberating gospel through word and deed. Our ministerial efforts extend beyond our local church, community and country; we strive to truly be a Church that speaks to the world. It is our prayer that you accept this invitation and visit St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and that God richly blesses you.  St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church

St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church

From The Labor History Archives -In

The 80th Anniversary Year Of The Great San Francisco, Minneapolis

And Toledo General Strikes- Lessons In The History Of Class Struggle

From The Archives Of The Socialist

Workers Party (America)- Some Lessons of the Toledo Strike

Frank Jackman comment:

Marxism, no less than other

political traditions, and perhaps more than most, places great emphasis on

roots, the building blocks of current society and its political organizations.

Nowhere is the notion of roots more prevalent in the Marxist movement that in

the tracing of organizational and political links back to the founders, Karl

Marx and Friedrich Engels, the Communist Manifesto, and the Communist League. A

recent example of that linkage in this space was when I argued in this space

that, for those who stand in the Trotskyist tradition, one must examine closely

the fate of Marx’s First International, the generic socialist Second

International, Lenin and Trotsky’s Bolshevik Revolution-inspired Communist

International, and Trotsky’s revolutionary successor, the Fourth International

before one looks elsewhere for a centralized international working class

organization that codifies the principle –“workers of the world unite.”

On the national terrain in the

Trotskyist movement, and here I am speaking of America where the Marxist roots

are much more attenuated than elsewhere, we look to Daniel DeLeon’s Socialist

Labor League, Deb’s Socialist Party( mainly its left-wing, not its socialism

for dentists wing), the Wobblies (IWW, Industrial Workers Of The World), the

early Bolshevik-influenced Communist Party and the various formations that made

up the organization under review, the James P. Cannon-led Socialist Workers

Party, the section that Leon Trotsky’s relied on most while he was alive.

Beyond that there are several directions to go in but these are the bedrock of

revolutionary Marxist continuity, at least through the 1960s. If I am asked,

and I have been, this is the material that I suggest young militants should

start of studying to learn about our common political forbears. And that

premise underlines the point of the entries that will posted under this

headline in further exploration of the early days, “the dog days” of the

Socialist Workers Party.

Note: I can just now almost hear some very nice and proper

socialists (descendants of those socialism for dentist-types) just now,

screaming in the night, yelling what about Max Shachtman (and, I presume, his

henchman, Albert Glotzer, as well) and his various organizational formations

starting with the Workers party when he split from the Socialist Workers Party

in 1940? Well, what about old Max and his “third camp” tradition? I said the

Trotskyist tradition not the State Department socialist tradition. If you want

to trace Marxist continuity that way, go to it. That, in any case, is not my

sense of continuity, although old Max knew how to “speak” Marxism early in his

career under Jim Cannon’s prodding. Moreover at the name Max Shachtman I can

hear some moaning, some serious moaning about blackguards and turncoats, from

the revolutionary pantheon by Messrs. Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky. I rest

my case.

********************

Trotskyist Work in the Trade Unions

by Chris Knox

Part 4 of 4

Stalinism and Social-Patriotism

With the onset of World War II and the wave of jingoism which swept away their trade-unionist allies of the prewar period, the Trotskyists were forced to retreat. They adopted a "policy of caution" in the unions, which meant virtual inaction, especially at first. Although the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) was driven from its main base in the Minneapolis Teamsters through a combination of government persecution and attack by the Teamsters bureaucracy and the Stalinists, in general the "policy of caution" had the desired effect of protecting the trade-union cadre from victimization.However, the "policy of caution" had another side to it. With the rupture of their alliances with the "progressive" trade unionists, the Trotskyists had not dropped their reliance on blocs around immediate issues in the unions. They merely recognized that with both the Stalinists and "progressives" lined up for the war, Roosevelt and the no-strike pledge, there was no section of the trade-union bureaucracy with which they could make a principled bloc. Thus their inaction was in part a recognition that any action along the lines to which they were accustomed in the trade unions would be opportunist, i.e., would necessarily entail unprincipled blocs and alliances. Any action not involving blocs and alliances with some section of the trade-union bureaucracy was virtually inconceivable.

At first, the rupture of the earlier alliances and enforced inactivity had a healthy effect, exposing the limitations of such alliances and enforcing the recognition that in trade-union work as in all other spheres of party-building, only principled political agreement assures permanence:

"There is only one thing that binds men together in times of great stress. That is agreement on great principles....

"All those comrades who think we have something, big or little, in the trade union movement should get out a magnifying glass in the next period and look at what we really have. You will find that what we have is our party fractions and the circle of sympathizers around them. That is what you can rely on.... The rule will be that the general run of pure and simple trade unionists, the nonpolitical activists, the latent patriots--they will betray us at the most decisive moment. What we will have in the unions in the hour of test will be what we build in the form of firm fractions of convinced Bolsheviks."As the war dragged on, however, opportunities for activity mounted as the workers chafed under the restrictions imposed upon them by their leaders in the name of the imperialist conflict. Rank-and-file rebellion, in the form of unauthorized strikes, broke out in a mounting wave starting in 1942. These led to mounting opposition to the solid, pro-war bureaucratic phalanx. For the most part, the SWP went very slow on participation in these struggles. It wasn't until 1945 that a formal change of policy was made, although exceptions to the rule began earlier.--James P. Cannon, "The Stalinists and the United Front," Socialist Appeal, 19 October 1940

While seeking to preserve their precious trade-union cadre through a policy of inaction within the unions, the Trotskyists concentrated on public propaganda and agitational campaigns aimed at the unions largely from the outside, through the party press. The campaign against the war centered largely on the defense case of the Minneapolis 18--the 18 Trotskyists and leaders of the Minneapolis Teamsters who were railroaded to jail under the Smith Act.

Minneapolis Defense Case

The 18 were the first victims of the Smith Act of 1940, which was the first law since the Alien and Sedition Act of 1798 to make the mere advocacy of views a crime. Initiated in 1941 directly by Roosevelt (ostensibly at the request of Teamsters President Tobin), the case was an important part of the drive by the bourgeoisie, working hand-in-hand with its agents, the labor bureaucrats, to "purify" and discipline the work force for subordination to the imperialist war. The legal persecution consummated Tobin's attempts to get rid of the Trotskyists in Minneapolis, which had coincided with the lining up of the bureaucracy for the war.However, because of its clear and open contradiction with the stated principles of bourgeois democracy, and thus with the stated goals of the war, the Smith Act prosecution of the Trotskyists caused a rupture within the bureaucracy and became a point of opposition to the government throughout the labor movement. Publishing the testimony of the chief defendant, James P. Cannon, and the closing, argument of the defense attorney, Albert Goldman, as pamphlets (Socialism On Trial and In Defense of Socialism), the SWP exploited the case heavily as a basic defense of socialist ideas and principled opposition to the imperialist war. Though they failed to prevent the destruction of the militant Minneapolis Teamsters local under the combined hammer blows of Tobin and Roosevelt, the Trotskyists' propaganda campaign around the case had a significant impact and aided party recruiting.

The vicious treachery ot the Stalinists was underlined and exposed to many by their refusal to defend the Trotskyists against this persecution by the class enemy. Despite the fact that the CP was still opposed to the entry of the U.S. into the war at the time (during the Hitler-Stalin Pact period, 1939-41), it leapt at once onto the prosecutor's bandwagon.

"The Communist Party has always exposed, fought against and today joins the fight to exterminate the Trotskyite Fifth Column from the life of our nation."More than any other force on the left, it was Stalinism, through such fundamental betrayals of class principles as this, which poisoned class consciousness and undermined the fighting ability of the proletariat. Later, during the cold-war witchhunt, when the CP was the victim of the same Smith Act and bureaucratic purge, the militant workers were so disgusted with its role that they were mobilized by anti-communist bureaucrats who smashed virtually every last vestige of class-conscious opposition in the labor movement. Despite its strong position within the CIO bureaucracy in 1941, the CP was unable to prevent the CIO and many of its affiliates from denouncing the Minneapolis prosecution; in 1949, however, the CP's betrayal of the Minneapolis defendants was held up to it by opportunists in the CIO as an excuse for not defending it against the witchhunt. The Trotskyists defended the CP in 1949, but the CP refused their help, wrecking its own defense committees in order to keep Trotskyists out.--Daily Worker, 16 August 1941

Defense Policy Criticized

While the conduct of the Trotskyists' defense in the Minneapolis trial was a good defensive exposition of the ideas of socialism, it was clearly deficient in not taking an offensive thrust, in failing to turn the tables on the system and to put it on trial. The Spanish Trotskyist Grandizo Munis raised this criticism, among others, of the SWP leaders' defense policy. Although he failed to take sufficiently into account the need for defensive formulations to protect the party's legality, Munis correctly complained of a lack of political offensive in Cannon's testimony."It was there, replying to the political accusations--struggle against the war, advocacy of violence, overthrow of the government by force--where it is necessary to have raised the tone and turned the tables, accuse the government and the bourgeoisie of a reactionary conspiracy; of permanent violence against the majority of the population, physical, economic, moral, educative violence; of launching the population into a slaughter also by means of violence in order to defend the Sixty Families."In his reply, Cannon condemned Munis for demanding ultra-left adventurist "calls to action" instead of propaganda, but he failed to adequately answer the charge of political passivity and of a weak, defensive stance. His reply ("Political Principles and Propaganda Methods") overemphasized the need to patiently explain revolutionary politics to a backward working class, lacking in political consciousness. After the war, when the shackles of war discipline were removed from the working class, this error was inverted in an overemphasis of the momentary upsurge in class struggle.--"A Criticism of the Minneapolis Trial"

Lewis and the Miners: 1943

Most of the opportunities for intervention in the unions during the war consisted in leading rank-and-file struggles against a monolithic, pro-war bureaucracy. The exception to this pattern was Lewis and the UMW. Having broken with Roosevelt before the war because of what he felt to be insufficient favors and attention, Lewis authorized miners' strikes in 1943 which broke the facade of the no-strike pledge. This galvanized the opposition of the rest of the bureaucracy, which feared a general outpouring of strike struggles. Not only the rabidly patriotic, pro-war CP, but other bureaucrats as well, heaped scorn on the miners, calling them "fascist."While the SWP was correct in its orientation toward united-front support to Lewis against the government and the bulk of the trade-union bureaucracy, the tone of this support failed to take into account the fact that Lewis was a reformist trade unionist, completely pro-capitalist, who therefore had to betray the eager following he was gathering by authorizing strikes during the war. He did this, performing what was perhaps his greatest service for capitalism, by heading off the rising tide of sentiment for a labor party. Focusing opposition to Roosevelt on himself, Lewis misled and demoralized masses of workers throughout the country by advocating a vote for the Republican, Wendell Wilkie, in the 1944 elections. Instead of warning of Lewis' real role, the Militant appears not only supportive but genuinely uncritical during the 1943 strikes.

"[Lewis] despite his inconsistencies and failure to draw the proper conclusions...has emerged again as the outstanding leader of the union movement, towering above the Greens and Murrays as though they were pygmies, and has rewon the support of the miners and the ranks of other unions."Though written from the outside, and therefore unable to intervene directly, the articles on the 1943 miners' strikes by Art Preis nevertheless reveal an unwarranted infatuation with Lewis which was evoked by the SWP's over-concentration on blocs with left bureaucrats, to the detriment of the struggle for revolutionary leadership.--Militant, 8 May 1943

The struggle against the no-strike pledge reached its highest pitch in the United Auto Workers, which had a militant rank and file and a tradition of democratic intra-union struggle not because of the absence of bureaucracy, but because of the failure of any one bureaucratic tendency to dominate. Despite their fundamental agreement on the war and no-strike pledge, the counter-posed tendencies continued to squabble among themselves as part of their endless competition for office. The wing around Reuther tried to appear to the left by opposing the excesses of the Stalinists such as the latter's proposal for a system of war-time incentive pay to induce speed-up, but in reality was no better on the basic issue of the war.

Auto Workers Fight the No-Strike Pledge

The struggle reached a peak at the 1944 UAW convention. Debate around the issue raged through five days of the convention. The highly political delegates were on their toes, ready for bureaucratic tricks. On the first day, they defeated by an overwhelming margin a proposal to elect new officers early in the convention and insisted that this be the last point: after positions on the issues were clear. The Reuther tendency dropped to its lowest authority during the war because of its role in saving the day for the no-strike pledge, through proposing that the pledge be retained until the issue could be decided by a membership referendum.The convention was marked by the appearance of the Rank and File Caucus, an oppositional grouping organized primarily by local leaders in Detroit. It was based on four points: end the no-strike pledge, labor leaders off the government War Labor Board, for an independent labor party and smash the "Little Steel" formula (i.e., break the freeze on wage raises). This caucus was the best grouping of its kind to emerge during the war. A similar local leadership oppositional grouping in the rubber workers' union was criticized by the SWP for its contradictory position: while opposing the no-strike pledge and War Labor Board, it nevertheless favored the war itself (Militant, 26 August 1944).

The SWP's work around the UAW RFC was also a high point in Trotskyist trade-union work. Though representing only a partial break from trade-union reformism by secondary bureaucrats, the RFC was qualitatively to the left of the bureaucracy as a whole. Its program represented a break with the key points upon which the imperialist bourgeoisie relied in its dependence on the trade unions to keep the workers tied to the imperialist aims of the state, The SWP was correct to enter and build this caucus, since pursuance of its program was bound to enhance revolutionary leadership.

The SWP's support, however, was not ingratiating or uncritical as was its early support to Lewis. As the caucus was forming before the convention, the SWP spoke to it in the following terms, seeking to maximize political clarity:

"This group, in the process of development and crystallization, is an extremely hopeful sign, although it still contains tendencies opposed to a fully-rounded, effective program and some who are still reluctant to sever completely their ties with all the present international leaders and power cliques.

"There is a tendency which thinks that all the auto workers' problems will be solved simply by elimination of the no-strike pledge. They fail to take into account the fundamental problem: that the basic issues confronting the workers today can and will be solved, in the final analysis, only by political means."--Militant. 2 September 1944

| UAW leaders in 1945: (from left) Frankensteen, Addes, Thomas, Reuther. SWP trade-union policy concentrated on blocs with bureaucrats, rather than building revolutionary pole, first backing Reuther, then Thomas-Addes. |

Despite encouraging developments such as this, the SWP did not formalize a general return to activity in the unions until 1945, when it made a belated turn to a perspective of "organizing left-wing forces" around opposition to the no-strike pledge, War Labor Board, and for a labor party. In 1944, a small oppositional grouping was formed in the SWP by Goldman and Morrow based on Stalinophobia and a perspective of reunification with the Shachtmanite Workers Party, which had split off in 1940. On its way out of the SWP, this grouping was able to make factional hay out of the "policy of caution." Referring to the SWP's inactivity, a member of this faction asked pointedly, "When workers do move on a mass scale, why should they follow anyone who did not previously supply some type of leadership?" (A. Winters, "Review of Our Trade Union Policy," Internal Bulletin Vol. VI, No. 9, 1944).

Replying to the Goldman-Morrow group, the SWP majority specifically ruled out caucuses such as the RFC as a general model, claiming that the left wing could not be built by presenting the masses with a "ready-made" program, but only by working within the existing caucus formations. Since the RFC was led primarily by politically independent secondary UAW leaders, "existing caucus formations" could only mean a policy of entering the major bureaucratic power groupings, which is exactly what the SWP did on its return to activity after the war. Despite the comparative impotence of the trade-union bureaucracy and different nature of the tasks in the early thirties, the Minneapolis experience was cited as an example in defense of a policy that emphasized blocking with sections of the bureaucracy and avoiding the presentation of a program independent of, and counterposed to, the bureaucracy in the unions.

This was the perspective followed by the SWP in the post-war period. In the brief but extensive post-war strike wave--the most massive strike wave in U.S. labor history--the SWP emphasized its enthusiasm for the intense economic struggles and under-played its alternatives to the bureaucracy. Against the Goldman-Morrowites, the majority explicitly defended a policy of avoiding criticism of UAW leadership policy at the beginning of the 1946 GM strike in order to maintain a common front with the bureaucracy against the company. For a small revolutionary force of only 2,000 (this figure represented rapid growth at the end of the war period) to take such an attitude toward the vast trade-union bureaucracy simply served to weaken the forces which could have built revolutionary leadership by struggling against the inevitable bureaucratic betrayals.

| Leaders of SWP and Local 544 imprisoned in 1941 Minneapolis Smith Act trial. Standing, from left: Dobbs, DeBoer, Palmquist, Hamel, Hansen, Coover, Cooper. Sitting, from left:Geldman, Morrow, Goldman, Cannon, Dunne, Skoglund, Carlson. |

This revolutionary optimism was not matched in the trade unions by the open preparation of revolutionary leadership through "third group" caucuses, however, but by an orientation first toward the more progressive bureaucratic reformists who were leading strike struggles or breaking with their previous allies, the discredited Stalinists. Later, as the cold war set in, the SWP broke with its allies and oriented more toward the Stalinists. As in the late thirties, these orientations tended to be based not on maximum political clarity but on the trade-union issues of the moment. Unlike the late thirties, however, the situation changed rapidly into a general purge of reds and hardening of a conservative bureaucracy, with which no blocs were possible. Furthermore the united fronts of the post-war period tended to take the form of critical support for one faction over another in union elections. Besides having a demoralizing effect on the ranks of the SWP's trade-union cadre, the Trotskyists' failure to present a hard, distinctive revolutionary alternative in the unions in this period thus contributed to the formation of the new bureaucratic line-up and thereby to the eventual cold-war defeats.

Critical Support for Reuther: 1946

Again the UAW is the most important example, since in 1946 in that union the SWP had perhaps its best case for a policy of blocs. After the war, Reuther began a drive for domination of the union with a show of militancy. He led a 113-day strike against General Motors on the basis of the three-point program: open the books to public inspection, negotiations in public and wage increases without price increases. Though he made his basic support of capitalism and the "right" to profits clear, he was able to mobilize militant sentiment with this program, strike a left posture at the 1946 convention and win the presidency of the union from the Stalinist-backed R.J. Thomas.Reuther, however, made no effort to fight for and deepen the "GM strike program" at the convention. Though he won most of his votes on the basis of this militant strike program, his real program was opposition to the CP. This appealed to militants also, of course, since the CP had been completely discredited by its thoroughly right-wing role during the war (which it had incredibly attempted to extend into the post-war period--the so-called permanent no-strike pledge--on the basis of the Soviet bureaucracy's hopes for post-war peaceful coexistence with its capitalist allies). However, Reuther's caucus also attracted conservative anti-communists such as the American Catholic Trade Unionists (ACTU). The Militant exposed Reuther's basic conservatism even on trade-union issues by pointing out that he had devised the "one-at-a-time" strategy (isolating strikes against one company at a time); that he had endorsed the introduction of the "company security" clause into the Ford contract and had capitulated to Truman's "fact-finding" panel in the GM strike against the will of the elected negotiating body (23 March 1946). It also pointed out that his written program was no better than the Stalinist-backed Thomas-Addes caucus program "except for language and phraseology" (30 March 1946). Nevertheless, the Trotskyists critically supported his campaign for president because of the fact that the militant workers were voting for him on the basis of the GM strike program.

With skillful demagogy, Reuther had successfully coopted the militant wing of the union, including the earlier Rank and File Caucus (which had dissolved into the Reuther caucus). An approach to this militant wing which would have driven a wedge between the militants and Reuther was,needed. In 1944 the SWP had argued "that the time was not ripe for the independent drive of the RFC--despite the fact that these "unknowns," only running one candidate and without any serious effort, had secured 20 percent of the vote for president at the 1944 convention (Fourth International, October 1944). Yet the SWP had not hesitated to raise programmatic demands on the RFC as it was forming, in order to make its break with the bureaucracy complete. In 1946, however, despite criticisms of Reuther, in the last analysis the SWP supported him simply on the basis of his popularity and without having made any programmatic demands whatsoever on him (such as that he break with the conservative anti-communists as a condition for support).

Critical Support for Thomas-Addes: 1947

An independent stance might have left the SWP supporters isolated at the 1946 convention, but the establishment of such a principled pole would have helped recruit militants by the time of the next convention in 1947. Instead, the SWP simply tailed the militants--or thought it tailed the militants--once again. In the interval between the two conventions, Reuther consolidated his position on the basis of anti-communism--including support for Truman's foreign policy--and bureaucratic reformism. At the 1947 convention, the SWP switched its support to the Thomas-Addes caucus, on the grounds that the militants were already fed up with Reuther and an attempt had to be made to halt the latter's drive toward one-man dictatorial rule. For this bloc, there wasn't even the pretense of a programmatic basis. Despite the shift of Reuther to the right and the phony "left" noises of Thomas-Addes and the Stalinists, however, Reuther's complete slate was swept into office largely because of the discredited character of the previous leadership. Only after this debacle did the SWP put together an independent caucus. If such a course had been unrealistic before, after the 1947 convention it was more hopeless than ever. By that time, however, there was no other choice.The SWP's course in other unions was similar. In the National Maritime Union, for instance, the SWP supported Curran when he broke from his former Stalinist allies on the basis of democracy and militancy, even though he was already lining up for Truman's foreign policy and letting the Stalinists get to the left of him on militancy. Later, the SWP had to support the Stalinists against his vicious, bureaucratic expulsions.

Cold War and Cochran-Clarke

In 1953 the SWP was racked by a faction fight and split which in part reflected the penetration into the party of the kind of trade-union "politics" it had been pursuing in the unions. What had looked like a hopeful situation in the immediate post-war period had turned rapidly into its opposite. The betrayals and self-defeating policies of the Stalinists had combined with "reformist trade-unionist illusions to allow not only the consolidation of a monolithic, conservative trade-unidn bureaucracy, but the successful purge of reds from the unions and the nurturing of right-wing anti-communism within the working class, which made the international cold-war drive of U.S. imperialism virtually unopposed at home.The purge and pressure of the cold war caused a section of the SWP trade-union cadre to become disillusioned and give up on the perspective of building a vanguard party in the U.S. This defeatism was organized into a tendency by Cochran, on the basis of liquidation of virtually all public party activity in favor of a "propaganda" orientation which would have left the Cochranites, many of whom were officers in the UAW, free to make their peace with the Reutherite bureaucracy.

The Cochranites made an unprincipled combination with forces in New York around Bartell, Clarke and others who considered themselves the American representatives of the Pablo leadership of the Fourth International. Objectifying the post-war creation of deformed workers states in Eastern Europe and Yugoslavia into an inevitable, world-historic trend, the Pablo leadership proposed, in essence, that Stalinist and reformist leaderships could be forced to the left by the pressure of their mass base into creating more such states in a situation in which the imminence of World War III made the creation of independent Trotskyist parties impossible: the Trotskyist task, therefore, was to liquidate into the Stalinist and social-democratic parties. It was this essentially liquidationist perspective which brought Cochran and Clarke together into a temporary amalgam in the SWP.

While defending the twists and turns of the SWP trade-union policy, Cannon nevertheless indicated that these twists and turns might have had something to do with the degeneration of the cadre into material for Cochranite liquidationist opportunism:

"Factional struggles in the trade unions in the United States, in the primitive, prepolitical stage of their development, have been power struggles, struggles for office and place, for the personal aggrandizement of one set of fakers and the denigration and discreditment of the other side....

"Cochran's conception of 'power politics' in the party; his methods of conducting a factional fight--come from this school of the labor fakers, not from ours."The main cause of Cochranite liquidationism lay in the pressures of the cold war and wittchhunt, which had of course, been completely beyond the control of the SWP. Howevers Cannon's own documents defending the party against trade-unionist combinationism and liquidationism make clear that the party's position in the trade unions had been insufficiently distinct from "struggles for office and place," just as it had been insufficiently distinct from blocs with progressive Rooseveltians before World War II.--"Some Facts About Party History and the Reasons for its Falsification," Internal Bulletin, October 1953

In the course of pursuing a trade-union policy based almost exclusively on making blocs on the immediate trade-union issues, the SWP had gradually adapted to trade unionism and become less discriminating in whom it blacked with and why. Unlike the Stalinists and Shachtmanites, the Trotskyists maintained their class principles by refusing to make unprincipled alliances or by breaking them as soon as they became untenable. (Thus the SWP switched sides in the UAW in 1947 while the Workers Party of Shachtman pursued Reuther et. al. into the arms of the State Department.) In the final analysis, the SWP remained a principled party of revolutionary socialism by struggling against the fruits of its trade-union work internally and accepting the split of 20 percent of its mem= bership in 1953 rather than making further concessions to trade unionism.

Spartacist League: Learn and Go Forward

The policy of making united fronts in the trade-union movement around the immediate issues is not in itself incorrect. What the SWP did wrong was to see this as its exclusive policy for all periods, except those in which no blocs could be made without gross violations of principle, in which case the answer was to do nothing. In any period of normal trade-union activity, blocs can be made around immediate issues. The task of revolutionists is to forge a cadre, within the unions as well as without, armed with a program to break the unions from their role as instruments for tying the workers to capitalism and imperialism. Such a program must go beyond immediate issues and address all the key political questions facing the working class and provide answers which point to a revolutionary policy and leadership.While the Trotskyists advanced the struggle for revolutionary leadership dramatically with the right united front at the right time, as in Minneapolis in 1934, they more often tended to undermine their own party building with an exclusive policy of blocs, some of which had little or no basis for existence from the standpoint of revolutionary politics. By presuming that it was necessary for a small force to prove itself in action against the class enemy before it could present itself independently to the workers as an alternative leadership, the Trotskyists' united fronts tended to increasingly take the form of promoting someone else's leadership.

The Spartacist League sees as the chief lesson from this experience not the need to reject united fronts, occasional blocs or the tactic of critical support in the trade unions, but the need to subordinate these tactics to the task of building a revolutionary political alternative to the bureaucracy within the unions. A bloc or tactic of electoral support which fails to enhance revolutionary leadership through undermining the bureaucracy as such can only build illusions in reformism. The central conclusion is that there is no substitute for the hard road of struggle to inject a political class perspective of proletarian internationalism into what is normally a narrow, nationalist and parochial arena of struggle. Especially in the initial phases of struggle when the revolutionary forces are weak, it is necessary to make an independent pole as politically distinct as possible, so that the basis for future growth is clear. To this end, the SL calls for the building of caucuses based on the revolutionary transitional program.

BACK UP

Thursday, September 18, 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)