The Communist, in the American imagination, has always been the ultimate outside agitator.

No matter how homegrown a resistance movement was, or how local the organizers were, the first response from those facing protest has always been to blame an outsider. This was as true for town hall protests during the February 2017 congressional recess as it was for anti-lynching struggles more than 80 years ago during the Great Depression.

For much of the past century in this country, this undesirable alien — seen as being from someplace foreign and in need of deportation back there — stood accused of invading to stir up trouble where there was none, where previously the locals had been docile and willing to accept whatever everyday inequality was their lot. Though many Communists were indeed immigrants, who would be targeted for harassment and deportation for as long as the party existed, many, too, were homegrown, born and raised in the same cities and towns as their persecutors.

The Communist Party U.S.A., founded in 1919, was closely tied to what emerged as the Soviet Union after the 1917 October Revolution, but the American party also drew on decades of local radical organizing. Many of its members came out of the Socialist Party, the labor movement and even anarchist activism, but the party also found a base among African-Americans when Communists proved willing to take on their struggles for self-determination.

In short, American Communism was a movement that grew out of what the historian Robin D. G. Kelley, the author of “Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression,” calls “the most despised and dispossessed elements of American society.” It was the black workers drawn to the party, Professor Kelley argues, who shaped its political choices as much as the varying dictates that came from the Communist International, Moscow’s directorate for foreign parties.

During the Depression, the party took on fights not just for better wages and working conditions but also against evictions by landlords and abuses of the criminal punishment system. In the Deep South, the battle for freedom for the Scottsboro Boys, nine black teenagers falsely accused of rape in 1931, was led by the International Labor Defense, a legal arm of the Communist Party U.S.A.

That stand still inspires activists today. The Scottsboro case was what drew the organizer and educator Mariame Kaba, who runs the blog Prison Culture, to learn more about the Communist Party U.S.A.

“They were helping nine young black men,” she said, “and preventing their state-sanctioned murder for a crime they didn’t commit.”

The party inspired loyalty for reasons beyond simply an affinity for Marxist ideas. It was the campaigns Communists ran against police brutality, the practice of lynching and the Jim Crow laws that made their politics relevant to the lives of ordinary people. In the North as well as the South, on soapboxes on the streets of Harlem as well as on plots of sharecropped land in Alabama, Communist organizing addressed the bread-and-butter concerns of black people.

Communists believed that organizing the working class would work only if white workers realized that their liberation, too, was bound up with the fate of black workers. Facing this threat, anti-Communists and segregationists worked hard to sustain the fractures. They blamed Communists for fomenting “race mixing,” evoking sexualized fears that social equality would mean black men having sex with white women — the very fears that put the Scottsboro Boys on trial. In turn, when black people agitated for civil rights, the Bull Connors of the world called such demands Communist-inspired, returning to the same narrative of dangerous outsiders.

Such an argument said, in effect, that black people had to be whipped up by radical foreigners in order to challenge the remnants of slavery in the Jim Crow South, and that without those outsiders, America was, to steal a phrase from the 2016 election, already great. The view also ignores that it was the black members of the Communist Party U.S.A., raised in such circumstances, who made it clear that their struggles for economic independence were bound up with the racist violence they faced from both the police and white supremacist groups.

Those black Communists often had to fight to hold their party accountable to its professed ideals when the party shifted its strategy toward courting white liberals. The debates that resurfaced during the 2016 election cycle, about the primacy of race or class in left-wing organizing, particularly around the primary campaign of Bernie Sanders, echoed these past battles.

In the 1930s, the party taught its members to discuss their problems using the language of exploitation. This language meant that people “understood that racism and what they called male chauvinism wasn’t simply people acting badly or being psychologically controlled or being ignorant,” Professor Kelley said. “It was about the benefits that they derived from exploitative relationships.”

That framework, which has been revisited today in platform documents like “A Vision for Black Lives,” argues that racism, at root, is not about hate between groups, but about the way power is held in society. And class, according to this analysis, is created by relationships of exploitation.

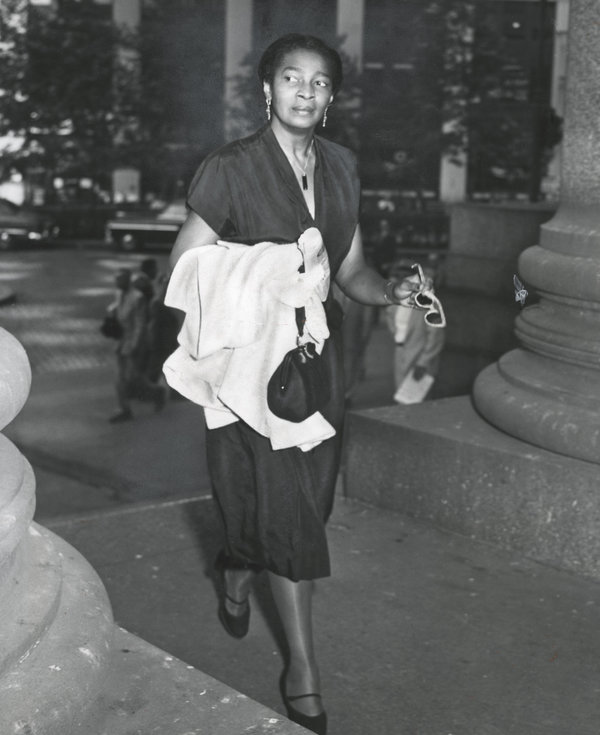

These arguments were championed by organizers like Claudia Jones, a black leader within the Communist Party U.S.A. and a journalist for its newspaper, The Daily Worker. According to Charlene Carruthers, the national director of Black Youth Project 100, Ms. Jones expounded the idea now known as intersectionality decades before that term became so ubiquitous that Hillary Clinton used it in a tweet on the campaign trail. For Ms. Jones, understanding the lives of black women and the economic and social position they occupied would create a better understanding of the system of capitalism as a whole. It followed, Ms. Carruthers explains, that black women’s work was central in the struggle to replace the system.

Within organized labor, particularly the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the 1940s, the Communist-led unions were consistently the leaders on racial and gender equality. Sometimes this clashed with the wishes of white male members, who occasionally went on strike against the inclusion of black members. With the eventual purge of such so-called red unions from the federation, the cause of antiracism slipped to the sidelines. Only in the past decade or so has it returned as a priority for some unions.

The Communist Party U.S.A.’s support for the nonaggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union at the beginning of World War II — a seeming betrayal of its strong anti-fascist stance — splintered the party’s membership. Revelations after the war about Stalin’s crimes further damaged the party’s international prestige. For the most part, in the West, Communist parties never recovered from those blows. At the same time, the end of the war hastened the demise of the old European empires, and Communists often took leading roles in the new anticolonial movements.

The story of Claudia Jones is instructive here, also. Born in Trinidad in 1915, she moved to New York with her family in the 1920s. In 1948, she was arrested for her political activism, tried under the McCarran and Smith Acts, imprisoned for several years and eventually deported, settling in London. She was one of many victims of the Red Scare that crushed American Communism and spurred purges, blacklists, deportations and a few high-profile executions.

Whipped-up fear of foreign terror around outsider Communists like Ms. Jones finds an echo today in the rhetoric of criminal immigrants and the scaremongering about “radical Islamic terror.” The techniques of McCarthyism have resurfaced, this time to evoke the threat of terrorism rather than Communism.

Yet for all the work that went into killing the idea that another system was possible, the specter of Communism haunts us still. The Communist Party U.S.A. had its greatest successes as the country reeled from the Depression. Today, as we are still picking our way out of the rubble left by the crash of 2008, left-wing ideas have gained new purchase. It was the material conditions of people’s lives, Ms. Kaba points out, that made them willing to listen to something radically different during the 1930s and ’40s. It was that economic reality that drove millions of people to pay attention to both the nationalist bombast of Mr. Trump and the democratic socialist message of Bernie Sanders.

That same reality drove organizers like Will Emmons of Lexington, Ky., to found new groups like the Kentucky Workers League, which Mr. Emmons says draws inspiration explicitly from the Communist Party of the ’30s and the work of the Black Panthers in the ’60s. The group has organized direct actions to defend people being evicted and offers community programs such as homework assistance at a local library. It ran a solidarity campaign with workers at a factory owned by Lexington-based Lexmark, contacting the workers in Mexico and pressuring the company locally to come to the table and bargain with the workers’ union. Since Mr. Trump’s victory, the group has turned to protecting immigrants in the community from deportation.

The year 2016 saw a revolt against politics as usual, with the mainstream parties’ failing to offer much in the way of solutions to struggling people across the United States. In the wake of the election, Ms. Carruthers said, organizations like Black Youth Project 100 have to broaden the scope of their work while cleaving to their political vision. Courting the supposed white mainstream while ignoring the material needs of black people, immigrants, transgender people and other marginalized communities will not placate Trumpian efforts to foment fear of the un-American outsider.

The power of the radical agitator — homegrown as well as outsider — has always been the ability to expose the gap between the narrative of American greatness and the realities of people’s lives. What American Communists, at their best, pioneered was to show how effectively grass-roots movements can challenge the racism, state violence and economic exploitation that people face in their daily lives, and connect those fights to a broader vision of a just world.

Sarah Jaffe (@sarahljaffe) is a Nation Institute fellow and the author of “Necessary Trouble: Americans in Revolt.”

This is an essay in the series Red Century, about the history and legacy of Communism 100 years after the Russian Revolution.