From The Marxist Archives -The Revolutionary History Journal-The Fourth International in France: from the POI to the PC1

...as usual the French section of the FI as the political epicenter of that organization was at the center of the turmoil about reconfiguring groups in the wake of the military defeat of the FI during this period.

Click below to link to the Revolutionary History Journal index.

Peter Paul Markin comment on this series:

This is an excellent documentary source for today’s leftist militants to “discover” the work of our forebears, particularly the bewildering myriad of tendencies which have historically flown under the flag of the great Russian revolutionary, Leon Trotsky and his Fourth International, whether one agrees with their programs or not. But also other laborite, semi-anarchist, ant-Stalinist and just plain garden-variety old school social democrat groupings and individual pro-socialist proponents.

Some, maybe most of the material presented here, cast as weak-kneed programs for struggle in many cases tend to be anti-Leninist as screened through the Stalinist monstrosities and/or support groups and individuals who have no intention of making a revolution. Or in the case of examining past revolutionary efforts either declare that no revolutionary possibilities existed (most notably Germany in 1923) or alibi, there is no other word for it, those who failed to make a revolution when it was possible.

The Spanish Civil War can serve as something of litmus test for this latter proposition, most infamously around attitudes toward the Party Of Marxist Unification's (POUM) role in not keeping step with revolutionary developments there, especially the Barcelona days in 1937 and by acting as political lawyers for every non-revolutionary impulse of those forebears. While we all honor the memory of the POUM militants, according to even Trotsky the most honest band of militants in Spain then, and decry the murder of their leader, Andreas Nin, by the bloody Stalinists they were rudderless in the storm of revolution. But those present political disagreements do not negate the value of researching the POUM’s (and others) work, work moreover done under the pressure of revolutionary times. Hopefully we will do better when our time comes.

Finally, I place some material in this space which may be of interest to the radical public that I do not necessarily agree with or support. Off hand, as I have mentioned before, I think it would be easier, infinitely easier, to fight for the socialist revolution straight up than some of the “remedies” provided by the commentators in these entries from the Revolutionary History journal in which they have post hoc attempted to rehabilitate some pretty hoary politics and politicians, most notably August Thalheimer and Paul Levy of the early post Liebknecht-Luxemburg German Communist Party. But part of that struggle for the socialist revolution is to sort out the “real” stuff from the fluff as we struggle for that more just world that animates our efforts. So read, learn, and try to figure out the

wheat from the chaff.

********

We reprint the following excerpt as a contrast to the summary of the activity of the French Trotskyists during the War provided by the account by Rodolphe Prager. It represents the view of the largest of the French Trotskyist organisations today, but which only consisted of some seven members during the first part of the Second World War.

After some years on the Central Committee of the POI, the official section of the Fourth International in France, the Romanian militant Barta (David Korner) decided that the French Trotskyist movement was incapable of breaking with its petit-bourgeois class composition and practices and of building an organisation of disciplined revolutionaries within the working class, and set up a new organisation in October 1939, which later became the Union Communiste. It turned its entire energies to the factories, where it distributed its bulletin, La Lutte des Classes regularly from October 1942 onwards. By April 1947 it was so well established that it led an important strike in Renault, which resulted in the expulsion of the Communist Party from the government when it failed to control it. By the 1960s it was distributing regular bulletins in dozens of factories as well as publishing a weekly newspaper, Voix Ouvrière (later Lutte Ouvrière). It played a most important part in the leadership of the strike of the French railway workers in 1987.

The extract below is translated from Les problemes du parti mondial de la Révolution et la Reconstruction de la IVe Internationale, Exposé du Cercle Leon Trotsky, 28 February 1966, pp.5-11, the full text of which was first published in English by Richard Stephenson in Documents on the History of the Fourth International No.1, Problems of the World Party of the Revolution and the Reconstruction of the Fourth International, London 1977. The full text of La Verité from which these extracts are taken can be consulted in La Verité 1940-1944. Journal trotskyste clandestin sous l’Occupation nazie, edited by J.M. Brabant, M. Dreyfus and J. Pluet, Paris, 1978, and, by contrast, the bulletin of the Union Communiste during the same period in La Lutte des Classes: Numéros clandestins de l’Occupation, Paris 1971.

But it is not for pleasure that we remain outside this organisation and that we had refused, at the unification of the French Trotskyist groups in February 1944, to place ourselves within the PCI that had just been born, nor was it, as these comrades accused us of at the time, a case of manufacturing divergences to justify our ‘autonomy’. It was for precise political reasons that we will return to today.

First of all, some comrades may be amazed that we should go back so far. This refers simply to the fact that our analysis begins from the foundation of the Fourth International and ends towards the 1950s, whereas other comrades take the period 1952-53 as a basis for analysis. For us, at that time the Fourth International had ceased to exist for some years as an organisation of the revolutionary vanguard.

When our comrades left the POI (French section of the Fourth International) in 1939, they wanted to distinguish themselves from an opportunist organisation. As far as they were concerned it was a matter of cutting themselves off from a petit bourgeois milieu whose practices were Social Democrat and not Communist. But at the time it was a matter of a critique of the French section and not of the totality of the organisations of the Fourth International.

The declaration of war saw the complete collapse of the French organisation of the Fourth International. Little prepared for clandestinity, a large number of militants found themselves in prison. The organisation dismantled itself.

In June 1940 the great majority of the elements of the Fourth International, grouped in the Comités francais pour une IVe Internationale completely abandoned the internationalist position in favour of a ‘common front with all the French-thinking elements’ and projected the creation of committees of ‘national vigilance’. In the Bulletin du Comité pour la IVe Internationale No.2 (20 September 1940) these comrades brought out the report adopted unanimously by the Central Committee of the Comité pour la IVe Internationale. Here are some extracts from it:

And during the war, La Verité, which successively entitled itself a Bolshevik-Leninist organ, a revolutionary Communist organ, the Central Organ of the French Committees for the Fourth International and the Organ of the POI, poured out nationalist prose in the name of Trotskyism, took up the slogans of the Committees of National Vigilance, and proposed an alliance of all the parties that wanted to defend the masses. Here, taking as examples, are some extracts from La Verité:

La Verité No.2 (15 September 1940)

La Verité No.8 (1 January 1941)

La Verité No. 11 (1 April 1941 )

These are no longer internationalist positions, this is nothing to do with Trotskyism.

The unification of the different Trotskyist groups (POI, CCI, October Group) took place at the beginning of 1944. The sponge was lightly passed over the chauvinist positions of 1940; all was forgotten; even better, they had always been right. In a common POI-CCI bulletin of July 1943, it is possible to read substantially that the POI had only committed the fault of using certain dangerous expressions in La Verité; the fundamental position was not only correct but perspicacious, for the POI had foreseen from 1940 the transformation of the national movement into a class movement.

Thus complete betrayal of internationalism is qualified as “dangerous expressions”. This is a delicate euphemism that unfortunately conceals something far more, for these comrades wrote in the unity declaration that appeared in La Verité on 25 March 1944 that since the beginning of the war: “These organisations had developed in consequence an international policy and activity” and furthermore; “At this decisive moment the Fourth International is regrouping its forces and correcting its faults by means of a Bolshevik critique.” The text simply makes allusion to “some episodic faults of this or that grouping”.

When in 1944 the French section of the Fourth International not only refused to recognise its errors but pretended that it had followed a correct line, it was evident that this section had nothing Trotskyist about it. As it was often to do later, the French section invented a whole theoretical arsenal to justify an opportunist practice: a national movement was spoken about in 1940-in the twentieth century in an imperialist country – in which two distinct resistances were discovered, one bourgeois and the other worker. This is what was written by our comrades in February 1944:

This attitude of the French section shows that in the political sphere (the events of 1939) as well as in that of principles (refusal of self-criticism, and self-justification at any price), opportunism reigned as master in its own house. For as far as we are concerned, it is not a case of refusing to unite under the pretext that the French section had made mistakes and grave faults. But a certain number of the militants of this Section recognised these errors but refused to admit to them in order not to injure the fusion. This attitude showed that this organisation had nothing Bolshevik about it, and that it was no longer the vanguard that Trotsky had wished to forge. And when after the war the Fourth International approved of the policy of the French section it was clear that it also was opportunist.

When the war ended, the French section was going to continue its politics. It was characterised on the domestic plane by tail-ending vis à vis the PCF. In the referendum of 21 October 1945 the PCI appealed for a ‘YES’ vote so that the Assembly would be a Constituent one. It launched an appeal to the Socialist Party and the Communist Party to form committees to defend the Constituent Assembly, and it demanded that the delegates should he elected and revocable at any time. It wanted to ‘sovietise’ more or less the bourgeois Constituent. Then it practised a policy of a left critique of the PCF, but absolutely not a revolutionary critique. From the most notorious nationalism, the PCI fell into the most vapid electoralism. This, incidentally, didn't prevent these comrades from regretting some months later “the persistence of parliamentary prejudices amongst the masses”.

And in the constitutional referendum of May 1946, the PC1 once again made a bloc with the so-called workers’ parties in voting ‘YES’ to the constitution.

And their argument was, to say the least, strange. In fact, you could read in La Verité of 28 April 1946:

But it was necessary to vote ‘YES’ to prevent the triumph of reaction:

La Verité No. 120 (May 1946):

In the foreign sphere the same phenomenon of tail-ending Stalinism can be witnessed not only on the part of the French section but of the whole International. The International as a whole was seized with it, and the image of the French section was only a faithful reflection of other sections.

If the April 1946 Conference of the Fourth International called for the “immediate withdrawal of the forces of occupation” (USA-France-Britain, as regards Germany), it also refused the amendment of the British section asking for the withdrawal of Russian troops from the territories that they occupied (IVe Internationale, December 1946).

...as usual the French section of the FI as the political epicenter of that organization was at the center of the turmoil about reconfiguring groups in the wake of the military defeat of the FI during this period.

http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/revhist/backissu.htm

Peter Paul Markin comment on this series:

This is an excellent documentary source for today’s leftist militants to “discover” the work of our forebears, particularly the bewildering myriad of tendencies which have historically flown under the flag of the great Russian revolutionary, Leon Trotsky and his Fourth International, whether one agrees with their programs or not. But also other laborite, semi-anarchist, ant-Stalinist and just plain garden-variety old school social democrat groupings and individual pro-socialist proponents.

Some, maybe most of the material presented here, cast as weak-kneed programs for struggle in many cases tend to be anti-Leninist as screened through the Stalinist monstrosities and/or support groups and individuals who have no intention of making a revolution. Or in the case of examining past revolutionary efforts either declare that no revolutionary possibilities existed (most notably Germany in 1923) or alibi, there is no other word for it, those who failed to make a revolution when it was possible.

The Spanish Civil War can serve as something of litmus test for this latter proposition, most infamously around attitudes toward the Party Of Marxist Unification's (POUM) role in not keeping step with revolutionary developments there, especially the Barcelona days in 1937 and by acting as political lawyers for every non-revolutionary impulse of those forebears. While we all honor the memory of the POUM militants, according to even Trotsky the most honest band of militants in Spain then, and decry the murder of their leader, Andreas Nin, by the bloody Stalinists they were rudderless in the storm of revolution. But those present political disagreements do not negate the value of researching the POUM’s (and others) work, work moreover done under the pressure of revolutionary times. Hopefully we will do better when our time comes.

Finally, I place some material in this space which may be of interest to the radical public that I do not necessarily agree with or support. Off hand, as I have mentioned before, I think it would be easier, infinitely easier, to fight for the socialist revolution straight up than some of the “remedies” provided by the commentators in these entries from the Revolutionary History journal in which they have post hoc attempted to rehabilitate some pretty hoary politics and politicians, most notably August Thalheimer and Paul Levy of the early post Liebknecht-Luxemburg German Communist Party. But part of that struggle for the socialist revolution is to sort out the “real” stuff from the fluff as we struggle for that more just world that animates our efforts. So read, learn, and try to figure out the

wheat from the chaff.

********

A Constant Opportunism

The Fourth International in France:from the POI to the PC1

We reprint the following excerpt as a contrast to the summary of the activity of the French Trotskyists during the War provided by the account by Rodolphe Prager. It represents the view of the largest of the French Trotskyist organisations today, but which only consisted of some seven members during the first part of the Second World War.

After some years on the Central Committee of the POI, the official section of the Fourth International in France, the Romanian militant Barta (David Korner) decided that the French Trotskyist movement was incapable of breaking with its petit-bourgeois class composition and practices and of building an organisation of disciplined revolutionaries within the working class, and set up a new organisation in October 1939, which later became the Union Communiste. It turned its entire energies to the factories, where it distributed its bulletin, La Lutte des Classes regularly from October 1942 onwards. By April 1947 it was so well established that it led an important strike in Renault, which resulted in the expulsion of the Communist Party from the government when it failed to control it. By the 1960s it was distributing regular bulletins in dozens of factories as well as publishing a weekly newspaper, Voix Ouvrière (later Lutte Ouvrière). It played a most important part in the leadership of the strike of the French railway workers in 1987.

The extract below is translated from Les problemes du parti mondial de la Révolution et la Reconstruction de la IVe Internationale, Exposé du Cercle Leon Trotsky, 28 February 1966, pp.5-11, the full text of which was first published in English by Richard Stephenson in Documents on the History of the Fourth International No.1, Problems of the World Party of the Revolution and the Reconstruction of the Fourth International, London 1977. The full text of La Verité from which these extracts are taken can be consulted in La Verité 1940-1944. Journal trotskyste clandestin sous l’Occupation nazie, edited by J.M. Brabant, M. Dreyfus and J. Pluet, Paris, 1978, and, by contrast, the bulletin of the Union Communiste during the same period in La Lutte des Classes: Numéros clandestins de l’Occupation, Paris 1971.

But it is not for pleasure that we remain outside this organisation and that we had refused, at the unification of the French Trotskyist groups in February 1944, to place ourselves within the PCI that had just been born, nor was it, as these comrades accused us of at the time, a case of manufacturing divergences to justify our ‘autonomy’. It was for precise political reasons that we will return to today.

First of all, some comrades may be amazed that we should go back so far. This refers simply to the fact that our analysis begins from the foundation of the Fourth International and ends towards the 1950s, whereas other comrades take the period 1952-53 as a basis for analysis. For us, at that time the Fourth International had ceased to exist for some years as an organisation of the revolutionary vanguard.

When our comrades left the POI (French section of the Fourth International) in 1939, they wanted to distinguish themselves from an opportunist organisation. As far as they were concerned it was a matter of cutting themselves off from a petit bourgeois milieu whose practices were Social Democrat and not Communist. But at the time it was a matter of a critique of the French section and not of the totality of the organisations of the Fourth International.

The declaration of war saw the complete collapse of the French organisation of the Fourth International. Little prepared for clandestinity, a large number of militants found themselves in prison. The organisation dismantled itself.

In June 1940 the great majority of the elements of the Fourth International, grouped in the Comités francais pour une IVe Internationale completely abandoned the internationalist position in favour of a ‘common front with all the French-thinking elements’ and projected the creation of committees of ‘national vigilance’. In the Bulletin du Comité pour la IVe Internationale No.2 (20 September 1940) these comrades brought out the report adopted unanimously by the Central Committee of the Comité pour la IVe Internationale. Here are some extracts from it:

The French bourgeoisie has rushed into a blind alley. To save itself from revolution, it threw itself into Hitler’s arms. To save itself from this hold, it has only to throw itself into the arms of the revolution. We are not saying that it will do so cheerfully, nor that the faction of the bourgeoisie capable of playing this game is the most important: the majority of the bourgeoisie secretly awaits its salvation from England, a large minority awaits it from Hitler. It is to the “French” faction of the bourgeoisie that we hold out our hand …

However our policy on this plane must above all be orientated to that faction of the bourgeoisie that above all wants to be French, which feels that it can only look for its salvation from the popular masses, that is capable of giving rise to a petit bourgeois nationalist movement, capable of playing the card of the revolution (from right or from left, or eventually from right and from left).

We must be the defenders of the wealth accumulated by generations of the peasants and workers of France. We must also be the defenders of the magnificent contribution of French writers and scholars to the intellectual heritage of humanity, defenders of the great revolutionary and Socialist traditions of France.

Committees of National Vigilance

It is necessary to create organs of national struggle. The Committees of National Vigilance could either be permanent organisms or – and this form corresponds more to the necessities of the national struggle at the present necessarily illegal stage – could be temporary organisms …

Some slogans: the number of national slogans is infinite. We will only try here to highlight some of them:

'Down with the pillage of French wealth!

The corn that French peasants have raised, the milk of the cows they reared; the machines without which our workers will be without work and without bread; the laboratory apparatus created by the genius of our scholars, all this wealth must remain in France …

Withdraw the German money! The French people wishes to create by its work real wealth, and not to be cast into the misery of inflation …

And during the war, La Verité, which successively entitled itself a Bolshevik-Leninist organ, a revolutionary Communist organ, the Central Organ of the French Committees for the Fourth International and the Organ of the POI, poured out nationalist prose in the name of Trotskyism, took up the slogans of the Committees of National Vigilance, and proposed an alliance of all the parties that wanted to defend the masses. Here, taking as examples, are some extracts from La Verité:

La Verité No.2 (15 September 1940)

The Grain Office forecasts that 60 per cent of the French cereal harvest will go off to Germany. And the government says nothing. Is this in agreement with Hitler to starve the French? Brother peasant, oppose passive resistance to requisitions, sell your corn only to make bread for the women and children of France.

La Verité No.8 (1 January 1941)

All those who struggle against the oppressor and who are not workers must understand that the support of working class forces is necessary for the success of the national liberation struggle; that they must be assured of a labour law that will interest them in the defence and rebirth of the fatherland of which they make up the strength.

What must the National Union be?

500,000 English engineers are asking for the linking of their wages to the cost of living. They are pointing out that the price of food products has doubled without a corresponding increase in wages. In satisfying this just demand the English government is beginning to realise a real national solidarity against German imperialism, by dividing the weight equally between the different classes of the country and by defending the interests of the English workers.

La Verité No. 11 (1 April 1941 )

We know like our predecessors of 1871 that we had to take up arms for the national independence that was betrayed by the bourgeoisie …

These are no longer internationalist positions, this is nothing to do with Trotskyism.

The unification of the different Trotskyist groups (POI, CCI, October Group) took place at the beginning of 1944. The sponge was lightly passed over the chauvinist positions of 1940; all was forgotten; even better, they had always been right. In a common POI-CCI bulletin of July 1943, it is possible to read substantially that the POI had only committed the fault of using certain dangerous expressions in La Verité; the fundamental position was not only correct but perspicacious, for the POI had foreseen from 1940 the transformation of the national movement into a class movement.

Thus complete betrayal of internationalism is qualified as “dangerous expressions”. This is a delicate euphemism that unfortunately conceals something far more, for these comrades wrote in the unity declaration that appeared in La Verité on 25 March 1944 that since the beginning of the war: “These organisations had developed in consequence an international policy and activity” and furthermore; “At this decisive moment the Fourth International is regrouping its forces and correcting its faults by means of a Bolshevik critique.” The text simply makes allusion to “some episodic faults of this or that grouping”.

When in 1944 the French section of the Fourth International not only refused to recognise its errors but pretended that it had followed a correct line, it was evident that this section had nothing Trotskyist about it. As it was often to do later, the French section invented a whole theoretical arsenal to justify an opportunist practice: a national movement was spoken about in 1940-in the twentieth century in an imperialist country – in which two distinct resistances were discovered, one bourgeois and the other worker. This is what was written by our comrades in February 1944:

To be able – in a text explaining the official position – to transform the betrayal of the Fourth International movement into a fairy, tale of Bolshevik foresight (apart from “some errors“) the ideological level of the POI must be pretty low.

The pretexts invoked in a Stalinist manner by the POI must be rejected with disgust, whereby they blame their own faults on the masses. From this point of view it is typical that the POI-CCM organisations should attribute the collapse of the organisations of the Fourth International in France to the outbreak of the war, which had isolated the vanguard from the masses. Any revolutionary who did his job during the ‘Phoney War’ knows that this is pure fantasy; on the contrary, never had contact with the working masses been more easy (and not only with the working masses), never had the masses been more disposed to accept revolutionary propaganda …

This attitude of the French section shows that in the political sphere (the events of 1939) as well as in that of principles (refusal of self-criticism, and self-justification at any price), opportunism reigned as master in its own house. For as far as we are concerned, it is not a case of refusing to unite under the pretext that the French section had made mistakes and grave faults. But a certain number of the militants of this Section recognised these errors but refused to admit to them in order not to injure the fusion. This attitude showed that this organisation had nothing Bolshevik about it, and that it was no longer the vanguard that Trotsky had wished to forge. And when after the war the Fourth International approved of the policy of the French section it was clear that it also was opportunist.

When the war ended, the French section was going to continue its politics. It was characterised on the domestic plane by tail-ending vis à vis the PCF. In the referendum of 21 October 1945 the PCI appealed for a ‘YES’ vote so that the Assembly would be a Constituent one. It launched an appeal to the Socialist Party and the Communist Party to form committees to defend the Constituent Assembly, and it demanded that the delegates should he elected and revocable at any time. It wanted to ‘sovietise’ more or less the bourgeois Constituent. Then it practised a policy of a left critique of the PCF, but absolutely not a revolutionary critique. From the most notorious nationalism, the PCI fell into the most vapid electoralism. This, incidentally, didn't prevent these comrades from regretting some months later “the persistence of parliamentary prejudices amongst the masses”.

And in the constitutional referendum of May 1946, the PC1 once again made a bloc with the so-called workers’ parties in voting ‘YES’ to the constitution.

And their argument was, to say the least, strange. In fact, you could read in La Verité of 28 April 1946:

The Constituent sanctified compensation of big businessmen for firms nationalised and maintained imperialist exploitation of the colonial peoples. It recognised as inviolable the private property of the exploiters.

But it was necessary to vote ‘YES’ to prevent the triumph of reaction:

La Verité No. 120 (May 1946):

Since the MRP has made a bloc with the bourgeois parties against the ‘workers’ parties by calling for a ‘NO’ vote in the referendum, it is necessary to form a bloc with the latter to call for a ‘YES’ vote to prevent the plebiscite for or against the PCF-PS from turning to their advantage.

In the foreign sphere the same phenomenon of tail-ending Stalinism can be witnessed not only on the part of the French section but of the whole International. The International as a whole was seized with it, and the image of the French section was only a faithful reflection of other sections.

If the April 1946 Conference of the Fourth International called for the “immediate withdrawal of the forces of occupation” (USA-France-Britain, as regards Germany), it also refused the amendment of the British section asking for the withdrawal of Russian troops from the territories that they occupied (IVe Internationale, December 1946).

Singer

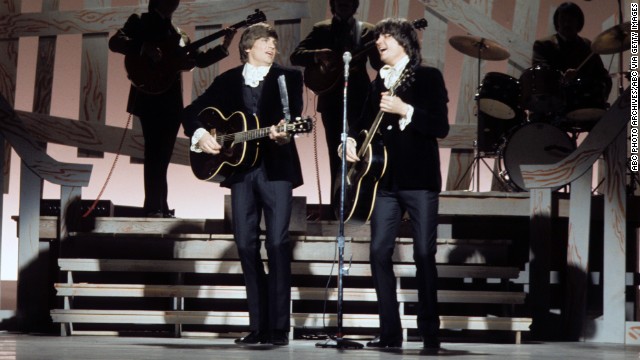

Singer During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Phil Everly and his brother, Don, ranked among the elite in the music world by virtue of their pitch-perfect harmonies and emotive lyrics.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Phil Everly and his brother, Don, ranked among the elite in the music world by virtue of their pitch-perfect harmonies and emotive lyrics.

Rolling Stone labeled the Everly Brothers "the most important vocal duo in rock," having influenced the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Simon & Garfunkel and many other acts. Here, they perform on the Johnny Cash Show in 1970.

Rolling Stone labeled the Everly Brothers "the most important vocal duo in rock," having influenced the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Simon & Garfunkel and many other acts. Here, they perform on the Johnny Cash Show in 1970.

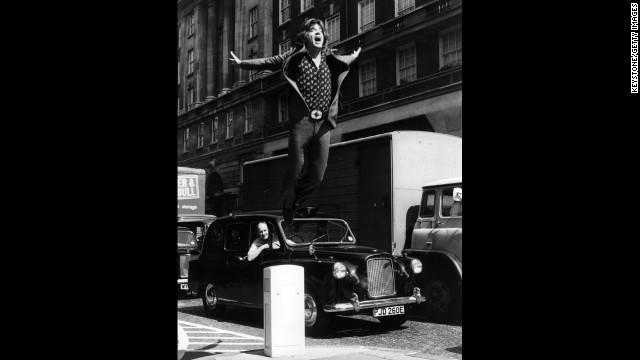

Phil Everly in London after signing a recording contract with Pye Records, having just recorded an album and a single, "Invisible Man," with his producer and close friend Terry Slater.

(CNN) -- Singer Phil Everly -- one half of the groundbreaking, smooth-sounding, record-setting duo, the Everly Brothers -- has died, a hospital spokeswoman said.

Phil Everly in London after signing a recording contract with Pye Records, having just recorded an album and a single, "Invisible Man," with his producer and close friend Terry Slater.

(CNN) -- Singer Phil Everly -- one half of the groundbreaking, smooth-sounding, record-setting duo, the Everly Brothers -- has died, a hospital spokeswoman said.