In Honor of John Brown Late Of Harpers Ferry -1859

Workers Vanguard No. 1139

|

September 2018

|

In Honor of John Brown

Part One

We print below the first part of a presentation, edited for publication, given by Spartacist League Central Committee member Don Alexander at a February 24 Black History Month forum in New York City.

I was just handed a piece of paper with a quote by James P. Cannon, founder of American Trotskyism, that I want to start with. It’s from his speech on the way to prison in 1943, when 18 Trotskyist and Minneapolis Teamsters union leaders were jailed for opposing imperialist World War II. Cannon said, “The grandest figure in the whole history of America was John Brown” (printed in Speeches for Socialism [1971]). Over the years, a number of comrades have paid tribute to John Brown in North Elba, New York, where he is buried, and have given talks on different aspects of the Civil War and Reconstruction. We raise the slogans “Finish the Civil War!” and “For black liberation through socialist revolution!” to express the historic tasks that fall to the revolutionary party. Acting as the tribune of the people, a revolutionary workers party will fight for the interests of all the oppressed—black people, Latinos, women, Asians, immigrants and others. It will lead the working class to carry out a third American revolution, a proletarian revolution, the only road to the full integration of black people into an egalitarian socialist society.

The existence of black chattel slavery in the United States had a peculiar character. “Chattel” means personal property; it meant to own people like cattle to trade or kill. Comrades and friends will recall that veteran Trotskyist Richard S. Fraser underscored in his writings some 60 years ago how the concept of race was central to the development of American capitalism. He outlined how the material basis of black oppression drew upon a precapitalist system of production. Slavery played an important role in the development of British industrial capitalism and U.S. capitalism. British textile owners received Southern cotton, which was shipped by powerful New York merchants. New York merchants used some of this money to send manufactured goods to the South. Although slavery and capitalism were intertwined, they were different economic systems. There is an excellent presentation by comrade Jacob Zorn called “Slavery and the Origins of American Capitalism” (printed in WV Nos. 942, 943 and 944, 11 and 25 September and 9 October 2009).

I will add that the conflation of slaves with skin color didn’t exist in ancient slavery. But with regard to the U.S., the great black abolitionist Frederick Douglass put it well: “We are then a persecuted people not because we are colored, but simply because this color has for a series of years been coupled in the public mind with the degradation of slavery and servitude.” Black people constitute a race-color caste, with their color defining their so-called inferior status. In the majority, black people are forcibly segregated at the bottom of this racist, capitalist system, deemed pariahs and outcasts. Anti-black racism is ruthlessly promoted by the ruling class to keep the working class divided and to conceal the common class interests of working people against their exploiters.

Today, the filthy rich capitalists’ huge profits rest upon the backs of working people—black, immigrant and white. The rulers’ system of “checks and balances” has been and always will be that they get the checks while they balance their bone-crushing, anti-worker, anti-poor budgets on our backs! The multiracial working class, with a strategic black component, has the social power and the interest to champion the fight not only for black freedom, but of all the oppressed and to break the chains of wage slavery. Whether or not this is understood at the moment, the fight for black freedom is an inseparable part of the struggle for the emancipation of the entire working class from capitalist exploitation. The working class cannot take power without confronting and defeating centuries of black oppression. We say that those who labor must rule!

The Road to Harpers Ferry

In reflecting on John Brown, fellow abolitionist Harriet Tubman once said: We didn’t call him John Brown, we called him our “savior” because he died for our people. In the late 1950s and early ’60s, military veteran Robert F. Williams, who organized armed self-defense against the Klan and was driven out of the country on trumped-up kidnapping charges, carried around with him a copy of A Plea for Captain John Brown, an 1859 speech in defense of Brown by Henry David Thoreau. Malcolm X also praised John Brown.

The notion that John Brown was crazy, an insane mass murderer and a fanatic, is still peddled in bourgeois academia and cinema. The truth is that John Brown was a revolutionary who saw deeper than any other abolitionist that it would take a revolution, a bloody war to uproot slavery. John Brown did not dread that war. He did not deprecate it. He did not seek to avert it. And that is one reason why the bourgeoisie still looks at him with disdain and hatred.

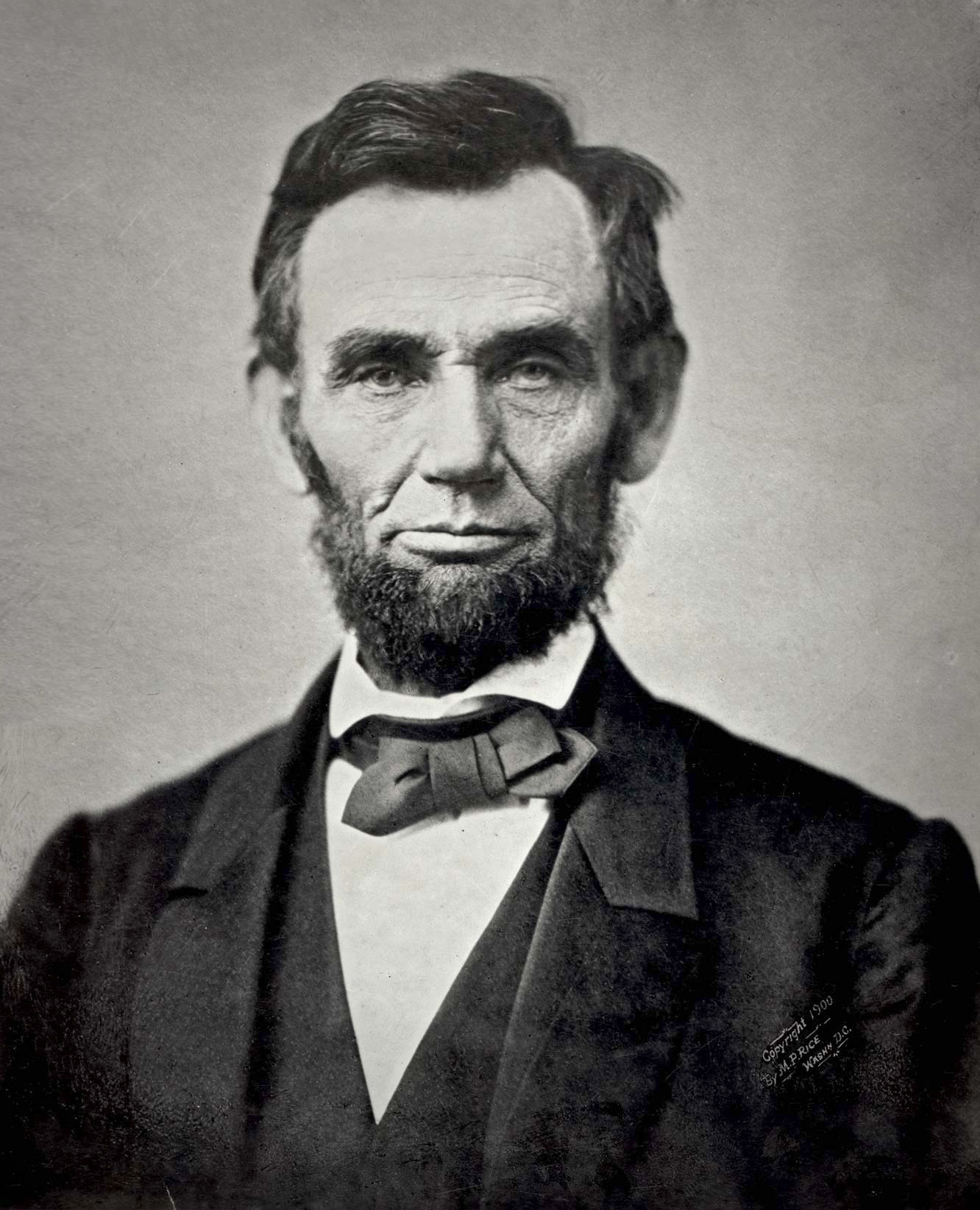

Along with Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, John Brown was part of the revolutionary wing of the abolitionist movement who saw the outlines of what was coming in the struggle to destroy chattel slavery. Abraham Lincoln was a good leader during the Civil War who, under pressure, did eventually make it an official war against slavery. John Brown’s final push against slavery had been to lead a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. For this, he and several of his followers were publicly executed by the State of Virginia in December 1859.

Summing up for the world his last thoughts before his hanging, John Brown hurled a bolt of lightning toward his captors and executioners, proclaiming that this land must be purged with blood—there needed to be revolution. He was almost 60 years old, which is quite amazing. How did John Brown become a revolutionary abolitionist dedicated to the destruction of slavery through force? From where did he think he would get the forces to accomplish his goals? What is the significance today of his struggle for black freedom?

John Brown was born in 1800. He was a generation removed from the first American Revolution which, while getting rid of British colonial oppression, left slavery intact and in most states gave suffrage only to propertied white males. He was deeply religious and raised by parents who hated slavery. His father Owen Brown, who had a significant influence on John, was a pacifist and a Calvinist as well as an active abolitionist, a stationmaster and conductor on the Underground Railroad. Fueled by Protestant beliefs, his family was tough and resourceful.

Owen subscribed to abolitionist papers like The Liberator, which John grew up reading. John Brown worked with his father on the Underground Railroad, gaining valuable experience for his future revolutionary activities. While herding cattle when he was 12 years old, John witnessed a young slave boy being pummeled mercilessly by a slaveholder with an iron shovel. This incident shook him to the core. John picked up on the fact that in contrast to the slave boy, he himself was treated very well by the slaveowner. This only infuriated John more. He knew that the slave boy was horribly oppressed and had nothing, not a mother and not a father. From that point on, John Brown declared eternal war on slavery.

Brown fervently believed in the “divine authenticity of the Bible.” His prayers were combined with a call to deliver the slaves from bondage. But he was not sitting back and waiting for his pie in the sky. As black historian Benjamin Quarles put it in Allies for Freedom: Blacks and John Brown (1974): “Prayer to Brown was a prelude to action, not a release from further involvement.” In his last days, he cursed hypocritical preachers and their offers of consolation, saying they should be praying for themselves.

John Brown and Abolitionism

I would like to briefly touch on the abolitionist movement. The U.S. abolitionist movement was part of the broader bourgeois radicalism in the 19th century, developing from radical elements of the Protestant Reformation and the 18th-century Enlightenment. It was also a product of the limitations of the first American Revolution, which continued the enslavement of half a million people. By John Brown’s time, the number of slaves had grown to four million.

In the beginning of his political awakening, John Brown admired the anti-slavery Quakers and also closely read The Liberator, which was put out by the most famous abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison of Boston. Some of the first abolitionists like Garrison had belonged to the American Colonization Society that formed in 1816. The Colonization Society was a racist alliance between abolitionists and slaveholders promoting the settlement of black Americans in Africa. The underlying purpose of the colonization scheme was to drive free blacks out of the country. Free blacks were viewed with suspicion that they might stir up slave rebellions. Black abolitionists, who saw the organization as anathema, bitterly and vigorously resisted colonization because it told black people that they should leave the land of their birth.

Starting in 1817, a series of black abolitionist conventions was organized in various cities in order to defeat this racist program, in what came to be known as the Negro Convention Movement. After attending the 1831 National Negro Convention, William Lloyd Garrison became radicalized and eventually sharply repudiated colonization. This gained him respect, admiration and support among abolitionists—especially black abolitionists.

There was considerable racism in the abolitionist movement. However, radical abolitionists had a wider vision for human emancipation. As we stated in Black History and the Class Struggle No. 5 (February 1988): “Although slavery was their preeminent concern, these radical bourgeois egalitarians also fought for many other pressing political issues of the time, such as free education, religious tolerance and workers’ rights.” The women’s suffrage movement first began as a fight within abolitionism over the role of women anti-slavery activists. Women’s rights leaders such as Angelina Grimké and her sister Sarah, who came from a slaveholding family, were staunch fighters for black freedom. They were clear on the connection between black and women’s oppression. Angelina said: “I want to be identified with the negro; until he gets his rights, we shall never have ours.” The radical egalitarianism embodied in this principled position also animated John Brown’s hatred of all oppression.

The beginning of the formation of white abolitionist organizations was the establishment of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Formed in 1832, it was galvanized by Nat Turner’s slave revolt a year prior, which killed some 60 white people. The revolt was followed by the execution of Nat Turner and his followers, and the massacre of a considerable number of black people.

William Lloyd Garrison represented the “moral suasion” wing of the abolitionists. Garrison also thought that the North should secede from the South, which objectively meant leaving the slaves helpless and defenseless. Although he sincerely hated slavery and wanted to see it destroyed, he stood for passive resistance. He rejected political action and instead put forward a futile program to appeal to the conscience of slaveowners to liberate their slaves. Garrison’s slogan of “No Union with Slaveholders” placed the struggle against slavery on the level of particular evils of individual slaveholders.

Frederick Douglass, who started out as a Garrisonian, strenuously objected to this slogan, recognizing that behind it was a defeatist strategy. He counterposed an aggressive fight against slavery. He instead raised in its place the slogan, “No Union with Slaveholding.” This was not a word play, but a different program and outlook. Douglass understood that the slaveholding system had to be destroyed, mainly through political means.

John Brown followed the debates and struggles of the abolitionists closely, especially those of the militant black abolitionists such as the young minister Henry Highland Garnet and David Walker, who advocated that the slaves rise up against their hated oppressors. According to social historian Robert Allen in his book Reluctant Reformers (1975), David Walker “was a free black who operated a small business in Boston, and in his spare time acted as a local agent for Freedom’s Journal, a black anti-slavery newspaper.” Walker argued that a “God of justice and armies” would destroy the whole system. His pamphlet, the Appeal, called for the immediate abolition of slavery.

But Walker was contradictory. He combined a militant stance of resistance to slaveholders with a call for the masters to repent and to voluntarily relinquish the slave system. He had explicit instructions on what the slaves must do when they rose up for their freedom: “Make sure work—do not trifle, for they will not trifle with you—they want us for their slaves, and think nothing of murdering us in order to subject us to that wretched condition—therefore, if there is an attempt made by us, kill or be killed.” The Southern planters wanted him captured dead or alive and enacted state bans on anti-slavery literature. Reportedly, both Walker’s Appeal and Henry Highland Garnet’s address to the 1843 National Negro Convention appeared together in a pamphlet that John Brown paid to produce. Brown would incorporate the spirit of Walker’s Appeal in his attempt to win black people to his revolutionary plans.

Transforming into a Revolutionary

As I mentioned earlier, as a young man, John Brown was an Underground Railroad operator. The Underground Railroad was bringing to the fore the most conscious elements of anti-slavery black radicalism. The great significance of the Underground Railroad, an interracial network of activists who were willing to risk their lives, was not the number of slaves it freed—which was perhaps 1,000 slaves per year out of a population of four million slaves. Its importance in the long run was that it crystallized a black abolitionist vanguard in the North. As the historian W.E.B. DuBois wrote, it “more and more secured the cooperation of men like John Brown, and of others less radical but just as sympathetic.”

In pursuing his growing commitment to black freedom, at age 34, John Brown wrote a letter to his brother about his aspiration to establish a school for black people. He understood the revolutionary implications of this: “If the young blacks of our country could once become enlightened, it would most assuredly operate on slavery like firing powder confined in rock, and all the slaveholders know it well.”

In the 1830s and ’40s, John Brown moved around a lot to earn a living and support his family. He went to Springfield, Massachusetts, and became more familiar with the lives and struggles of black people. Brown moved to North Elba in upstate New York, where well-known and wealthy radical abolitionist Gerrit Smith had donated land to be used by black people for farming. Brown forged ties with Smith as well as with radical black New York abolitionists like James McCune Smith and the Gloucester family of Brooklyn. He had many unsuccessful business pursuits, as a tanner, a land surveyor, a wool merchant. His travels while doing business enabled him to gain indispensable knowledge of the different strands of abolitionism in the Midwest and Northeast. From what he observed, he wasn’t impressed with the talkathons of abolitionist meetings. He never joined them because he disdained mere talk.

Brown was never able to set up a school, but he pressed on with teaching black people history and how to farm and carry out self-defense against slave catchers. His belief in social equality was clear. He shocked one white visitor to his home, who observed that black people were eating at the same table with the Brown family. The Browns showed respect to the black people there by addressing them as Mister and Missus.

John Brown kept his ear close to the ground, the better to follow and assimilate the thoughts of free and fugitive black people. Under the guise of a black writer, he wrote to a black abolitionist paper, the Ram’s Horn, to offer his frank opinions on how best to push forward black self-improvement. He didn’t hide his observations or criticisms of what he considered to be negative behaviors of some black people, ranging from flashy dressing to smoking—surely in accordance with his strict Calvinist morality. At the same time, he struggled to win them to the understanding that they should not meekly bow down to white racist aggression, but should resist it.

There was one major development that accelerated his transformation into a professional revolutionary. It was the 1837 violent killing of Elijah Lovejoy, the editor of an anti-slavery newspaper in Alton, Illinois. Lovejoy was attacked by a pro-slavery mob, which also hurled his printing press into the river. His murder shocked the abolitionist movement. Lovejoy was the first abolitionist martyr—and it could happen to any of them.

John Brown’s developing revolutionary social consciousness cost him some racist “anti-slavery” friends. As the biographer Tony Horwitz noted: “The Browns believed in full equality for blacks and were determined to fight for it” (Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War [2011]). The family’s resistance to segregation came to a head when they fought for integration in a Congregational church they attended. During a revival meeting, black people in attendance were seated in the rear of the church. At the next church service, Brown and his family gave up their seats and led the black worshippers to sit in theirs, located in the family pew. The deacons of the church were outraged and later wrote to them that they should find somewhere else to worship. This vile racism led John to distance himself from the institution of the church.

Preparing for Battle

Consciously wanting to link up with militant black abolitionists, John Brown put Frederick Douglass high on his list. Douglass and Brown had their first meeting in 1847 in Springfield, Massachusetts. Brown had avidly read Douglass’s abolitionist paper, The North Star (later Frederick Douglass’ Paper), and went on to share his developing plans. According to Horwitz:

“Brown pointed to a map of the Allegheny Mountains, which run diagonally from Pennsylvania into Maryland and Virginia and deep into the South. Filled with natural forts and caves, these mountains, Brown said, had been placed by God ‘for the emancipation of the negro race’.”

This meeting was a turning point in Douglass’s evolution from a protégé of Garrison into a revolutionary abolitionist. Brown fought to convince him of the futility of non-resistance to the slaveholders. He told him that the only thing the slaveowners appreciated was sticks upside their heads—something like that. Five years later, Douglass would abandon his naive faith in pacifist non-resistance. He began to openly state that slavery could be destroyed only through bloodshed, which shocked his former comrades.

Going forward, several challenges loomed for both revolutionary abolitionists, Douglass and Brown: the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the further expansion of slavery to the Western territories like Kansas, and the Dred Scott decision of 1857. The last involved a slave named Dred Scott who sued for his freedom on the basis that he had resided in a free state for many years. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney ruled against Scott and went on to assert that black people, free or slave, were not U.S. citizens. In the words of Taney, which are echoed by today’s modern-day slaveholders—the ruling class in this country—black people “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Let me say a few things about the continued expansion of slavery. The South’s cotton production was booming in the 1840s and ’50s. It supplied most of the world’s demand, outstripping other American exports combined. Northerners wanted slavery to stay put where it was.

Many white laborers were primarily concerned with having to compete with black people for jobs, not with the inherent brutality against and degradation of slaves. Some Northern states, such as Ohio and Illinois, had long enacted “Black Laws” that set controls on freed blacks and deterred black people from migrating there. Meanwhile, there were bloody land grabs under way, such as during the 1846-48 Mexican-American War, when the United States seized about half of Mexico’s territory. The appetites of slaveowners and prospective ones were whetted. The question was sharply posed: Could Southerners carry “their” property into new territories? Would those territories be free or slave?

The Compromise of 1850, which was contentious in Congress, concluded that California would be a free state, while the question of Utah and New Mexico was left to the white settlers to decide. Along with this, the new Fugitive Slave Act (the first was enacted in 1793) now mandated that ordinary citizens were required to aid in the capture and return of runaway slaves, even forming posses to do so. Northerners in effect became deputized slave catchers.

Douglass had plenty to say about the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. In 1852 he remarked: “The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers. A half dozen or more dead kidnappers carried down South would cool the ardor of Southern gentlemen, and keep their rapacity in check.” Anti-slavery fury was swelling in the North, and in places like Boston, slave catchers were set upon and fugitives freed. However, because the full power of the federal government lay behind the enforcement of the law, militant abolitionists were not always successful.

For his part, John Brown responded to the Fugitive Slave Act by forming a secret self-defense organization to fight slave catchers. The organization was called the United States League of Gileadites, named after Gideon, a figure in the Old Testament who repelled the attacks of enemies who far outnumbered his forces. Brown drew up a fighting program for the League called “Words of Advice.” In the League’s manifesto, he offered such tactics as “when engaged do not work by halves, but make clean work with your enemies…. Never confess, never betray, never renounce the cause.”

With a plan slowly germinating in his mind, John Brown was gathering the forces for the raid on Harpers Ferry. As then-Trotskyist George Novack wrote about Brown in January 1938 (printed in the New International), “By establishing a stronghold in the mountains bordering Southern territory from which his men could raid the plantations, he planned to free the slaves, and run them off to Canada.” Accordingly, Brown did a serious investigation of the terrain, including circling on a map figures on slave concentrations throughout the South. This information was discovered after he was captured at Harpers Ferry.

John Brown also prepared through reading and travel. A number of his business pursuits enabled him to go to places outside the U.S. like England, for example, where in 1851 he went seeking better prices for his wool. A key part of his trip to Europe was to inspect military fortifications, like at Waterloo where Napoleon met defeat. He studied military tactics and especially guerrilla war in mountainous terrain. He read books on Nat Turner’s revolt, the Maroons—the runaway slaves in Jamaica and other places who waged guerrilla warfare—and Francisco Espoz y Mina, the guerrilla leader in Spain during the Napoleonic Wars. He also had books on Toussaint L’Ouverture, leader of the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804, and a biography of the leader of the English Revolution of 1640, Oliver Cromwell. Brown was familiar with and recited for his friends and followers the story of Spartacus, who led a slave rebellion against Roman rule.

His preparations for war meant that he didn’t spend a lot of time with the rest of his family in North Elba. They understood and agreed, knowing that while he was away, it was their duty to resist the slave catchers, even if it meant imprisonment or death. Brown cared deeply for his family’s welfare and tried to alleviate some of their brutal poverty. He did what he could to support them as they all endured incredible hardships and suffered many setbacks. For example, John himself fathered 20 children and lost nine of them before they reached age ten, including three on three consecutive days. The Brown family knew that the cause of the slaves’ emancipation transcended their personal lives and they stuck it out, together. For John Brown, slavery was the “sum of villanies,” the ultimate atrocity against human freedom. And the fight lay ahead.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Workers Vanguard No. 1140

|

21 September 2018

|

In Honor of John Brown

(Part Two)

We print below the second part of a presentation, edited for publication, given by Spartacist League Central Committee member Don Alexander at a February 24 Black History Month forum in New York City. The first part appeared in WV No. 1139 (7 September).

I’m sure that most of you have heard that what’s so terrible about the abolitionist John Brown was that he was a heartless, bloodthirsty killer. These are longstanding bourgeois lies. The real John Brown fought for armed slave rebellion and organized armed struggle against the slave system in “Bleeding Kansas” in the 1850s.

In 1855, John Brown joined his four oldest sons who had migrated to Kansas to fight against it becoming a slave state and win the territory for the “free-soilers.” The free-soilers had been associated with the short-lived Free Soil Party, whose platform called both for barring slavery from western territories and for the federal government to provide free homesteads to white settlers. In 1854, many of the Party’s former members had gone on to join the newly established Republican Party, which was born on the platform of “free soil” and “free labor.”

It was a period of turmoil. Congress had just passed a new law called the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed the terms of the 1820 Missouri Compromise that was supposed to limit slavery’s expansion. Sponsored by a Northern Democrat, Stephen A. Douglas, the law allowed the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery within their borders. According to Karl Marx, the Kansas-Nebraska Act had “placed slavery and freedom on the same footing.” As he described it, “For the first time in the history of the United States, every geographical and legal limit to the extension of slavery in the Territories was removed” (“The North American Civil War” [1861]). The Kansas-Nebraska Act was nothing more than a signal for pro-slavery Missourians next door to invade and, through terror and violence, open Kansas to slavery.

At this point it was clear that there wouldn’t be, and couldn’t be, any lasting “compromises.” From the early days of the republic there evolved several sham “compromises” between the North and South. The first of these concessions, coming out of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, made slaves three-fifths of a person for the purposes of apportioning representatives to Congress; this gave the Southern slaveowners control of Washington. Now, the fundamental and irreconcilable class interests between the slavocracy and the Northern industrial bourgeoisie were coming to a head. One or the other would prevail. War was coming and Kansas was the next arena.

After some initial hesitation, Brown sought the approval of his black supporters and garnered the support of several radical abolitionists before joining his sons in Kansas. He decided that it was best to go there because it would be more important ultimately for the cause of freedom. From that point, his determination hardened and grew in the fight against slavery.

John Brown brought weapons and ammunition with him to Kansas to equip an anti-slavery militia where he was captain. He and his sons confronted a well-armed pro-slavery group of Missourians appropriately called the Border Ruffians, who were pouring into the state to terrorize free settlers. The free settlers needed an infusion of fresh blood to beat back a highly organized campaign of intimidation and murder. John Brown, his sons and supporters waged several successful battles in their defense. His militia retaliated for a number of murders of free settlers—in one night raid they killed five pro-slavery sympathizers near Pottawatomie Creek. Brown’s force struck fear into the hearts of the marauding pro-slavery bands.

Both the governor of Missouri and President James Buchanan, a Northern Democrat, offered rewards for Brown’s capture. Buchanan and other Northerners with Southern sympathies were called “doughfaces” because they were “half-baked and malleable.” Without John Brown’s intervention, which strengthened the free settlers’ morale and military defenses, a lot worse could have happened. It was not impossible that Kansas could have become a slave state.

Brown fought in Kansas throughout 1856. Toward the end of his stay, a Missouri slave crossed the border into Kansas, seeking help from anyone to keep him and his family from being sold. What do you think John Brown did? He led his militia to where the slaveholder was back in Missouri. His forces freed a number of slaves, eleven in all, including the family that was imperiled. A slaveowner was also killed. Brown’s militia seized horses and supplies to facilitate their escape and transport with the final destination being Canada. The local, state and federal authorities were outraged and over $3,000 was put on Brown’s head.

In the end, the slaves made it to Canada because of John Brown. In a frenzy, some of his abolitionist “friends” denounced him—not for seizing the slaves, but for the seizure of the slaveowners’ other personal property. And it’s not surprising, because some of these abolitionists were capitalists, for whom capitalist private property was sacred. For his part, John Brown had no trust in politicians from either political party. As author Stephen B. Oates noted in To Purge This Land With Blood (1970), Brown “hated the Democrats because he believed their party was dominated by the South and despised the Republicans because they were too ‘wishy-washy’ on the slavery issue.”

Roll Call for Harpers Ferry

The next arena for Brown was Chatham, Ontario. Chatham was a small town just east of Detroit and was a terminus on the Underground Railroad where thousands of fugitive slaves and free blacks resided. Living nearby in St. Catherines was Harriet Tubman. I’ll get back to her in a minute.

In Chatham in May 1858, John Brown convened a secret convention to debate the way forward and to finalize plans for the coming assault on and seizure of the federal armory and arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The primary aim of the convention was to seek recruits for this action. One of the more important parts of the convention was a programmatic document he submitted—the Provisional Constitution. It was no mere empty exercise, but the basis for a selection of an abolitionist vanguard for revolutionary war. John Brown was making plans for a future provisional egalitarian free-state government in the mountains.

Brown’s Provisional Constitution was seriously debated. Some delegates argued that the best time to have a coordinated attack somewhere in the South would be when the U.S. government was at war. But the argument to delay was defeated. There were delegates who rejected any reference to the flag of the United States as a symbol of freedom; they said, this is my oppression, the American flag. Brown argued that the flag was an expression of America’s early democratic ideals—a vote was taken and he won. It became the flag against slavery during the Civil War, but today it is the flag of imperialist plunder and mass murder, racial oppression and anti-immigrant bigotry.

When his business was finished in Chatham, he finalized his plans for Harpers Ferry. Brown tirelessly gave speeches to raise money for his war preparations, for the consummation of his life’s work to free the slaves. In need of more money for arms and supplies, he contacted a radical abolitionist group that he relied upon: the “Secret Six,” which included Franklin Sanborn and Gerrit Smith, who were animated by his Kansas exploits. However, he never revealed to them the specific target of his next strike.

Brown knew that in order to attract significant black support, it was vital to win over Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. Tubman was key to recruiting followers among the many freedmen and fugitives who had settled in Canada beyond the reach of the Fugitive Slave Law. Through her courageous Underground Railroad work, Tubman had extensive knowledge of the planned Appalachian route. Showing deep appreciation of her leadership skills, Brown called her the “General” or “He.” Tubman fully embraced Brown’s plans. She was organizing people to go with her, but she fell ill and didn’t make it. Unceasing toil and hardships, on top of terrible spells of unconsciousness and injuries sustained from beatings by slaveowners, had taken their toll. John Brown was deeply disappointed.

John Brown was about to lead 21 men to what would be in effect the first battle of the Civil War. As the time for action arrived, Brown met one last time with Frederick Douglass. It didn’t go well. He revealed his plans for seizing the armory and arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Douglass sharply disagreed and said that they were falling into a “perfect steel-trap” and would be crushed. They argued for several hours, and Douglass turned down the offer to go. However, at the meeting was a friend, an ex-slave named Shields Green, who was one tough fighter and became highly esteemed by John Brown and his associates. When questioned about going or staying, Green remarked: I think I’ll go with the Old Man. Four other black men went—Osborne Anderson, John Copeland, his uncle Lewis Leary and Dangerfield Newby (who in his 40s was the oldest black man to go). Newby was sturdy and immovable and joined to help get his wife and children out of slavery in Virginia.

Putting his plan into effect required meticulous preparation and sheer courage. To hide his forces from the eyes of the prying enemy, Brown required the assistance of trustworthy collaborators. His first pick was his wife Mary, for whom he had tremendous respect. It’s clear from his letters and correspondence that they shared and discussed the political news of the day. Brown’s 15-year-old daughter Annie and 16-year-old sister-in-law Martha were assigned to hold down the secret farmhouse five miles from Harpers Ferry, keeping watch and feeding soldiers. The men were John Brown men, so they knew how to help and keep the place clean. Though when they didn’t, they were set straight. The men were confined in a tiny place and stuffed in an attic. There they studied together, argued about the history of slavery and discussed Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason. They were nearly broken by tension and their discipline was weakened, but the courageous young women kept up their morale and cohesion.

The whole thing could have been blown when one of the neighbors, who had a habit of showing up unannounced, caught a glimpse of a black man in the farmhouse. She suspected that Annie was helping runaways and challenged her to an explanation, but Annie denied it. Annie devised a plan to silence her neighbor by providing her and her children with food and helping them with other tasks as long as necessary.

In a very interesting biography of the women in John Brown’s family called The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown’s Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism (2013), author Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz describes Annie’s “trial-by-fire inauguration into abolitionist activism.” Annie herself later described this as the most important period of her life. As Laughlin-Schultz remarked, “Though she did not march to Harpers Ferry in October 1859, Annie’s work in the Maryland countryside may have allowed Brown’s raiders to do so, and the work of Mary and Ruth [his wife and daughter] at North Elba helped smooth over the Brown men’s absences.”

The aim of John Brown was this: to procure arms, free slaves in the nearby area, lead his army into the mountains where they could establish a liberated area and, if need be, wage war against the slave masters. From a military point of view, Brown’s plan for Harpers Ferry was futile. His son Owen said it was like Napoleon trying to take Moscow. One of the reasons it failed was that Brown didn’t fully carry out his plans, which he admitted to afterwards. He also believed he was overly solicitous to his prisoners and relied on some of them to ward off the enemy’s blows. In the end, Brown’s forces killed five people but lost ten of their own. They held control for 36 hours, surrounded by gunmen from nearby towns and hamlets and eventually by federal troops. The troops were dispatched by President Buchanan, under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee, the future commander of Confederate forces during the Civil War (you know, the “honorable” man according to White House chief of staff John Kelly). Brown and most of his associates were rounded up and captured, though several managed to escape. Those who were not killed on the spot were railroaded and later hanged by the vindictive courts of Virginia.

The Aftermath

While they were defeated in the end, John Brown and his men certainly fought. The raid at Harpers Ferry was a bold but unsuccessful action staged by a small, determined, interracial revolutionary band. What soon followed was what abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison termed “the new reign of terror” against black people in the South and against any Northerner who dared raise his head. Southerners were conjuring up fears of more Nat Turner revolts.

Harpers Ferry also caused fright and panic among some of John Brown’s so-called radical abolitionist friends in the Secret Six—they burned their correspondence with him. Gerrit Smith claimed insanity and briefly checked into an asylum while others fled for Canada. Some of them had probably been, to put it mildly, surprised when they found out that the plan was an assault on a federal arsenal and armory. It was euphemistically described by Brown, referring to the Underground Railroad, as “Rail Road business on a somewhat extended scale.” Secret Six member Thomas Wentworth Higginson refused to capitulate. He had told Brown before the raid that he was “always ready to invest in treason,” and didn’t burn his papers or correspondence. He later led a black regiment in the Civil War.

Frederick Douglass solidarized with the raid in a piece called “Capt. John Brown Not Insane” (Douglass’ Monthly, November 1859):

“Posterity will owe everlasting thanks to John Brown...[for he] has attacked slavery with the weapons precisely adapted to bring it to the death.... Like Samson, he has laid his hands upon the pillars of this great national temple of cruelty and blood, and when he falls, that temple, will speedily crumble to its final doom, burying its denizens in its ruins.”

Douglass had a price placed on his head by the federal government and used a pre-planned trip to England to escape.

John Brown knew that the pro-slavery federal government and its State of Virginia hangmen were close to finishing him off. While imprisoned, Brown was unbowed and wrote and answered many letters to family, friends and supporters (who mostly endorsed his action only some time after the fact). Above all, he pushed very hard for financial help to his family. He said that had he interfered on behalf of the rich, the oppressors would have poured praise upon him. Instead, his whole life had been devoted to fighting for the liberation of the slaves, and now he was willing to pay the ultimate price.

As I said, John Brown despised the ruling-class politicians of his day. For their murderous, cruel and unjust laws, he denounced the government as being filled with “fiends in human shape.” Before his death, in a letter to the abolitionist wife of George L. Stearns, Brown stated his wishes to be escorted to the gallows not by some pro-slavery clergyman but by poor blacks, his people: “I have asked to be spared from having any mock; or hypocritical prayers made over me, when I am publicly murdered: & that my only religious attendants be poor little, dirty, ragged, bare headed, & barefooted Slave Boys; & Girls led by some old grey headed Slave Mother.”

Following his execution, there were memorial services of black and white abolitionists in several cities. There was international impact. French writer Victor Hugo had written a rousing appeal to stop his execution and that of his followers. (The British abolitionists sat on their hands.) Brown’s death was also keenly felt in Haiti, the country with the first and only successful slave revolution in the Western Hemisphere, which was against the French slaveholders in 1791. Haitians, who saw in John Brown the great revolutionary and liberator of black slaves, Toussaint L’Ouverture, organized gatherings and fundraisers for the Brown family in every corner of the country. In addition, there were German workers—the Red ’48ers—European refugees who came to the U.S. following the failure of the 1848 revolution, who ended up playing an important role in building up the Union Army. Alongside black people in Cincinnati, they marched to memorialize John Brown.

John Brown gave his all and championed the struggles of the oppressed worldwide, including the 19th-century Hungarian, Greek and Polish struggles against national oppression. And it was his revolutionary war that opened the road to the annihilation of slavery. As radical abolitionist Wendell Phillips noted: “History will date Virginia Emancipation from Harper’s Ferry. True, the slave is still there. So, when the tempest uproots a pine on your hill, it looks green for months—a year or two. Still, it is timber, not a tree. John Brown has loosened the roots of the slave system; it only breathes,—it does not live,—hereafter.”

George Novack wrote a tribute to John Brown, published in January 1938 in the New International, journal of the revolutionary Trotskyists at that time, the Socialist Workers Party. He captured the dialectical development of events, noting how a seemingly stable and eternal slavocracy contained the seeds of its own destruction: “Through John Brown the coming civil war entered into the nerves of the people in the many months before it was exhibited in their ideas and actions.”

His Body Moldering in the Grave —His Soul Marching On

The Civil War broke out less than two years after the execution of Brown and his comrades. The Civil War was the last great bourgeois revolution, the last progressive war of the U.S. bourgeoisie. Instead of a confederation of states, it consolidated a unified capitalist market under a United States of America.

In the fires of secessionist rebellion and total war, Douglass called for arming the slaves. For his part, Lincoln was reluctant to wage what he called a “remorseless revolutionary struggle” to crush the slaveholders. Facing ongoing military reverses, Lincoln changed in the course of the war. He was compelled to deploy powerful black arms—ultimately 200,000 black soldiers and sailors—who were critical in tipping the balance of forces against the slavocracy. At the war’s end more than 600,000 Americans lay dead.

We are told that slavery was a “stain” on this “great” capitalist democracy. This suggests it was an aberration, a deviation from an essential goodness. This is a perfumed lie. Slavery was a barbarous economic system built into the very foundations of U.S. capitalism. Its legacy stamps every aspect of social and economic life. The slaves were liberated through the Civil War. But with the undoing of subsequent Radical Reconstruction, the most democratic period in U.S. history for black people, the promise of black equality was crushed through Klan terror and defeated by political counterrevolution. This led to the consolidation of black people as an oppressed race-color caste toward the end of the 19th century.

John Brown considered himself to be an instrument of “God.” He believed that it was part of God’s will for him to liberate the slaves through force, unlike those preachers who pontificated about solace and consolation to the oppressed. We are atheists and dialectical materialists, and we base our revolutionary Marxist outlook firmly upon science. This means explaining the world from the world itself, not from some nonexistent “higher power.” In the face of natural occurrences, early human beings devised a system of mystical explanations for what they didn’t understand. Earthquakes, famines, sickness and death were not attributed to the workings of a material, physical world—a world that existed prior to and independent of human consciousness. In contrast to a materialist view, an idealist view maintains ideas, opinions and thoughts as primary and material reality as secondary. In his writings, Karl Marx asserts that “man makes religion, religion does not make man,” that “religious suffering is at one and the same time the expression of real suffering,” and that religion is the “opium of the people.”

When the hour of action arrived, John Brown’s advice was to be quick, not to trifle. That is good advice. Importantly, he also struggled firmly to win revolutionary abolitionists to the fight for black freedom. He knew his foibles well and wrote about them. But what comes through from those who knew him was not a sense of superiority, but his kindness. Though we should proceed with historical care in analogies, one could say that there was a similarity he shared with Oliver Cromwell—the great 17th-century Puritan revolutionary of England. Brown would, as Trotsky noted of Cromwell, hesitate at nothing to smash oppression.

We of the International Communist League (Fourth Internationalist) seek to build Leninist-Trotskyist vanguard parties that will hesitate at nothing in the fight to put the wealth of the world created by labor into the hands of labor itself through proletarian revolutions across the globe. Guided by a firm, revolutionary vanguard party, the workers will forge the class-struggle leadership of labor by ousting the agents of the bourgeoisie within the workers movement.

In racist capitalist America, we will remember those like John Brown and many others who waged war to throw off the shackles of the oppressed. Capitalism cannot be reformed—no ruling class ever has relinquished its power, its profits and accumulated wealth without a fight and it never will. This understanding is contrary to the illusions spread by the reformist socialists, such as the International Socialist Organization and Socialist Alternative, that you can pressure the Democrats to reform capitalism.

We understand that class struggle is the motor force of history. But this is not all. Even before Marx and Engels, bourgeois historians were writing about class struggle in France and elsewhere. We Marxists seek to extend this to recognizing the necessity for proletarian power, for proletarian dictatorship that will eliminate capitalism. We fight to end the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, the capitalists, as part of a transition to a classless society of material abundance.

We stand for the full integration of black people into an egalitarian socialist order, for revolutionary integrationism. This means integrated class struggle, mobilizing the social power of the proletariat to lead the fight against all manifestations of racial oppression, against racist police terror, against segregated education, against the hated Confederate flag of slavery and finally, to victory over the exploiters.

We fight to win a new generation of conscious workers and militant youth to take up the banner of genuine Marxism: Trotskyism. As a Leninist-Trotskyist vanguard party acting as a tribune of the people, we have no interests separate from the working class and oppressed. We fight for a communist future. We say: Remember John Brown and all our revolutionary heroes and heroines! We say: Finish the Civil War! For a third American Revolution! For black liberation through socialist revolution!