From

The Labor History Archives -In The 80th Anniversary Year Of The

Great San Francisco, Minneapolis And Toledo General Strikes- Lessons In The

History Of Class Struggle

San Francisco's maritime strike, which began May 9, 1934, tumbled out of control when the Industrial Association, made up of employers and business interests who wished to break the strike, and the power of San Francisco unions, began to move goods from the piers to warehouses.

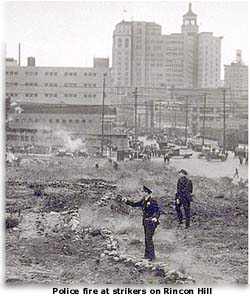

The first running battles between unionists and police began Tuesday, July 3, 1934. There was a lull during the July 4 holiday when no freight was moved, but disturbances picked up again Thursday, July 5, 1934 –

The area where the rioting took place is now the heart of San Francisco's Multimedia Gulch.

Industrial Association Moves Loads Off Piers at Rate of 10 an Hour.

To the accompaniment of widespread rioting, fist fights and popping of tear gas guns and bombs, the Industrial Association of San Francisco carried out its promise today to begin moving freight from the waterfront piers, blockaded since May 9 by the marine strike. About a score of persons were injured severely enough to require hospital treatment.

To the accompaniment of widespread rioting, fist fights and popping of tear gas guns and bombs, the Industrial Association of San Francisco carried out its promise today to begin moving freight from the waterfront piers, blockaded since May 9 by the marine strike. About a score of persons were injured severely enough to require hospital treatment.

Two men were shot and slightly wounded, a half dozen motor trucks were turned over and many persons suffered burning eyes from the gas.

But through it all, trucks moved at the rate of about 10 per hour from the McCormick Steamship Co.'s pier to a warehouse two blocks away.

That was because an area of several blocks, in which are the pier and the warehouse at 128 King st. where goods are being delivered, was kept free of strikers.

But on the outskirts of this area bellowing crowds of strikers and sympathizers were hurtling rocks at policemen, fighting through clouds of tear gas and damaging and overturning trucks.

Clubs Used Freely

Police used their clubs freely and mounted officers rode into milling crowds. The strikers fought back, using fists, boards and bricks as weapons. Rioting was widespread but was centered in the area surrounding the Southern Pacific Depot at Third and Townsend sts.

Several shots were fired in a battle near the railroad station. One bullet struck Eugene Dunbar, union seaman, in the left ankle. He was dragged out of the melee, tended by members of the crowd until an ambulance arrived and removed him to Harbor Emergency Hospital.

A stray bullet crashed through a window of the Bank of America branch at Third and Townsend, felling Berton Holmes, 24, a teller. He was cut over the left eye.

The Industrial Association announced no cars would be moved tomorrow, "because of the holiday."

Bricks Hit Police

One of the bloodiest bits of fighting occurred near the King st. warehouse. Suddenly the strike pickets broke through the police lines and surged around a pile of bricks. Soon the air was filled with missiles. Inspector Jerry Desmond went down, a cut over one eye. Asst. Inspector Cornelius was struck in the head. Officer John LaDue was struck in the leg with a brick.

Police Chief [William J.] Quinn led his men in person. He had a narrow escape when a brick crashed through the side window of his car, missing him by inches.

Another rock crashed through the windshield of a car driven by Sergt. Thomas McInerney as he was hurling tear gas bombs. Showered with glass, he escaped injury.

Another riot broke out at Second and Townsend sts. Police charged the crowd, but it did not move. The officers resorted to tear gas. Members of the mob, coughing and choking, picked up the smoking grenades and hurled them back into the police lines.

Windows of nearby buildings were crowded with onlookers. The gas began filtering through the windows and those watching the riot fell back, tears streaming from their eyes.

Police have a consignment of the new nauseating gas used so effectively in eastern riots, and Capt. Arthur DeGuire, head of Harbor Station, threatened to put it to use unless the rioters quieted down.

Another crowd tried to break through police lines along Second st. They streamed through South Park toward Third st. Police met them and drove them back slowly.

Trucks anywhere within blocks of the guarded area suffered, strikers mistaking them for machines moving cargo from the docks.

Cargo Dumped

Several strikers jumped on a truck at Third and Harrison sts., cowed the driver, and a companion, and started slitting its cargo of rice bags and dumping them into the streets.

At Third and Minna sts., they stopped the truck, beat the driver, Rex Hoffman, 21, Sacramento, and his companion, Bill Brooks. Both men escaped.

Later, at Harbor Emergency Hospital, where they were treated for cuts and bruises, Hoffman told police he was employed by the J.S. Smith Trucking Co., Sacramento, and was delivering a cargo of rice to the Phillips Milling Co., 38 Drumm st., and had no connection with the strike.

H.E. Foster, president of the Phillips Company, sent a protest to Mayor Ross, charged the truck was on a peaceful mission to Sacramento. Strikers had contended the truck came from the vicinity of the King st. warehouse.

R.T. Custi, 4049 Third st., was driver of another truck, and was employed by the Phillips Mill Co., Drumm st. Strikers slugged him, split open the rice bags, spilling their contents.

Another truck was stopped at Second and Townsend sts, and precipitated the rioting there. Strikers tried to tip it over, but were driven back.

Strikers attacked another truck on Third st. near Townsend and swarmed all over it. Ropes around a trailer were cut and the windows of the cab were smashed before tear bombs began dropping among the rioters.

Trucks Overturned

Still another truck was halted and overturned at First and Harrison sts.

Later, police were rushed to Fourth and Townsend, where two more trucks had been attacked and overturned.

These two trucks, one empty, the other loaded with empty boxes, were heading away from the Embarcadero toward the Hockwald Chemical Co. Part of the crowd chased the drivers, who escaped.

Gasoline and oil were oozing from the motors of the overturned machines. The crowd surged forward, men shouting, "Set the damn trucks on fire." Police drove them back. Time passed and the crowd began gathering again. When 1000 men were present, the mob rushed the trucks, began trying to tear them up. Police charged, driving them back again.

Fires Over Heads

The mob was blocking streetcars and mounted police tried to clear a path so that passengers could be escorted to cars on the other side of the crowd. Bricks began to fly through the air. Finally a policeman drew his gun and opened fire over the heads of the crowd.

Police fired shots again in the same vicinity when strikers began to hurl rocks at them over a passing freight train.

Several false alarms were turned in and the screaming of sirens from fire trucks added to the pandemonium. The Industrial Association blamed strikers for it.

Three men were arrested for turning in the alarms.

While this was going on, matters were proceeding peacefully enough in front of Pier 38, for strikers could not get within several blocks of the pier.

It was at 1:24 p.m., more than an hour behind schedule, that the first movement of cargo began.

The big steel doors of the pier rumbled up and two trucks emerged. One was a closed affair, loaded with auto tires. The second, which had an open body, was half filled with sacks of cocoa beans.

Twenty feet from the pier a line of police radio cars had been driven end to end across the Embarcadero, forming a complete blockade.

Two men were on each truck, a driver and a helper. They looked scared.

Behind the trucks were six policemen mounted on motorcycles. They swing in around the two machines as they turned south on the Embarcadero, heading for the warehouse.

Jeered by Thousand

A block away, in front of Pier 32, 1000 strikers swayed against police lines, shouted jeers and cures.

Fifteen minutes after they had left the two trucks returned peacefully to the pier. Their progress had been unimpeded while riots were going on on the outskirts of the closed area.

As the two empty trucks swung into the pier, three more loaded ones set out for the warehouse. Only a police radio car escorted them.

The trucks continued to shuttle back and forth–

A serious accident was narrowly averted when a fire engine came roaring down the Embarcadero. Police saw it coming and hurried to the line of cars blockading the right of way, getting two of them out of the path just as the fire engine shot through, its brakes screaming.

The biggest crowds of picketers were held in check at Second and Townsend sts., and in front of Piers 30 and 32. More than 1000 men had gathered at the former spot and fully 2000 at the piers.

Smaller Groups Halted

Smaller groups were halted at First and Brannan and at the [Mission] Channel.

Clearing of the area began two hours before the scheduled hour of opening. One striker tried to object while police were moving the crowd back. Five officers grabbed him and hustled him into a waiting police car.

At noon, the hour scheduled for the first truck to move, the atmosphere grew electric. Motorcycle policemen kicked up the stands on their machines, threw one leg over the saddle. Foot patrolmen outside the dock and in the cleared area gripped clubs and riot guns more firmly.

But the hour passed and the tension relaxed somewhat.

More Pickets Sought

Meanwhile, the joint marine strike committee had sent out a plea to all unemployed members of every labor union to come down and join the picket lines, no matter whether they were on strike or not. The committee claimed several thousand answered the call.

At dawn groups of strikers had begun to gather on the Embarcadero across from the pier. The numbers grew as the day progressed.

Brick Piles Guarded

On King between Second and Third sts. were two piles of bricks left by a construction company. Uniformed officers stood guard over each pile, although, when the trouble started they were unable to keep the mob from them.

A score of police were stationed north of the pier. As large groups of strikers began arriving from I.L.A. headquarters they were turned back or broken up into smaller groups.

Despite a plea from Police Chief Quinn that they stay away from the waterfront, crowds of curious also assembled on nearby vantage points.

Developments Listed

Highlighted against the ominous background of today's activities were the following developments late yesterday and overnight:

Stating that the job of keeping order on the waterfront was "up to the police," P.W. Meherin, president of the State Board of Harbor Commissioners, declared he would make no request for special policemen to guard the docks.

"If police find they can't take care of the situation, they can inform me and I'll take it up with the governor," he said.

"If police find they can't take care of the situation, they can inform me and I'll take it up with the governor," he said.

"If police find they can't take care of the situation, they can inform me and I'll take it up with the governor," he said.

"If police find they can't take care of the situation, they can inform me and I'll take it up with the governor," he said.

In Sacramento, Gov. Merriam said he had no intention of calling the National Guard at present, and would act only if requested by city officials or if state property is endangered.

Gov. Merriam said he may cancel engagements to review an Oakland parade and speak in San Francisco tomorrow if the strike trouble becomes too serious.

"It may be necessary for me to stay here, in the office, where I can be reached quickly," he said.

Mayor Rossi called a conference yesterday to discuss the situation. Informed that the national Longshoremen's board expected important advice from Washington this morning, he requested the postponement.

The advices have not arrived, the President's board said.

The mayor continued active today in efforts to avoid trouble. He conferred for some time with Edward Vandeleur, president of the San Francisco Labor Council, and admitted he was attempting to reach the strikers through organized labor. He also said he had been in touch with both sides in the dispute, but had not yet conferred with members of the President's board.

Later, the mayor issued a statement, appealing for both parties to acquiesce to the latest arbitration appeal of the President's board, urging there be no violence and calling upon citizens to stay away from the waterfront.

Decision of the State Harbor Commissioners not to employ additional dock guards came after a conference with police officials.

"We're not in the police business," said Mr. Meherin. "If we hired a large group of special policemen, some one would have to train them, organize them, command them. Our regular wharfingers and collectors are special policemen and their duty is to protect the docks. I'm not going to request special policemen to reinforce their numbers. If police can't handle the situation, and the docks are actually endangered, the next move would be up to the governor.

"We're not in the police business," said Mr. Meherin. "If we hired a large group of special policemen, some one would have to train them, organize them, command them. Our regular wharfingers and collectors are special policemen and their duty is to protect the docks. I'm not going to request special policemen to reinforce their numbers. If police can't handle the situation, and the docks are actually endangered, the next move would be up to the governor.

"We're not in the police business," said Mr. Meherin. "If we hired a large group of special policemen, some one would have to train them, organize them, command them. Our regular wharfingers and collectors are special policemen and their duty is to protect the docks. I'm not going to request special policemen to reinforce their numbers. If police can't handle the situation, and the docks are actually endangered, the next move would be up to the governor.

"We're not in the police business," said Mr. Meherin. "If we hired a large group of special policemen, some one would have to train them, organize them, command them. Our regular wharfingers and collectors are special policemen and their duty is to protect the docks. I'm not going to request special policemen to reinforce their numbers. If police can't handle the situation, and the docks are actually endangered, the next move would be up to the governor.

Michael J. Casey, president of the Teamsters' Union, who said yesterday that the teamsters "would not break strike for anybody," was asked if they would handle goods moved from the docks after they had been delivered to the warehouses.

"We'll cross that bridge when we come to it," he answered.

Lee J. Holman, who organized a right-wing union of striking longshoremen, called upon the membership to "get back to work as fast as possible, or it will be too late."

"There are a lot of husky young fellows working right now, and they are learning the business fast," he said. "One hundred more members of our union went back to work last night and today. That makes 200 in all now at work and they are making an average of $15 a day."

Following San Francisco's lead, the city of Emeryville took steps to break the strangle hold the strike has there. The City Council empowered Police Chief E.J. Carey to hire additional police and buy equipment. His first move was the installation of four giant floodlights to illuminate the industrial district.

San Francisco News

San Francisco News