Leon Trotsky

Political Profiles

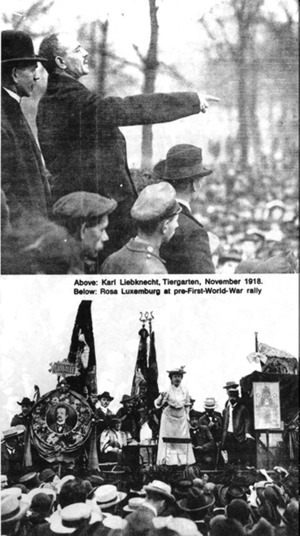

Karl Liebknecht and

Rosa Luxemburg

(1919)

WE HAVE suffered two heavy losses at once which merge into one enormous bereavement. There have been struck down from our ranks two leaders whose names will be for ever entered in the great book of the proletarian revolution: Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. They have perished. They have been killed. They are no longer with us!

WE HAVE suffered two heavy losses at once which merge into one enormous bereavement. There have been struck down from our ranks two leaders whose names will be for ever entered in the great book of the proletarian revolution: Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. They have perished. They have been killed. They are no longer with us! of anger and imprecation; this was the voice of Karl Liebknecht. And it resounded throughout the whole world!

of anger and imprecation; this was the voice of Karl Liebknecht. And it resounded throughout the whole world!In France where the mood of the broad masses then found itself under the heel of the German onslaught; where the ruling party of French social-patriots declared to the proletariat the necessity to fight not for life but until death (and how else when the ‘whole people’ of Germany is craving to seize Paris!); even in France Liebknecht’s voice rang out warning and sobering, exploding the barricades of lies, slander and panic. It could be sensed that Liebknecht alone reflected the stifled masses.

In fact however even then he was not alone as there came forward hand in hand with him from the first day of the war the courageous, unswerving and heroic Rosa Luxemburg. The lawlessness of German bourgeois parliamentarism did not give her the possibility of launching her protest from the tribune of parliament as Liebknecht did and thus she was less heard. But her part in the awakening of the best elements of the German working class was in no way less than that of her comrade in struggle and in death, Karl Liebknecht. These two fighters so different in nature and yet so close, complemented each other, unbending marched towards a common goal, met death together and enter history side by side.

Karl Liebknecht represented the genuine and finished embodiment of an intransigent revolutionary. In the last days and months of his life there have been created around his name innumerable legends: senselessly vicious ones in the bourgeois Press, heroic ones on the lips of the working masses.

In his private life Karl Liebknecht was—alas!—already he merely was the epitomy of goodness, simplicity and brotherhood. I first met him more than 15 years ago. He was a charming man, attentive and sympathetic. It could be said that an almost feminine tenderness, in the best sense of this word, was typical of his character. And side by side with this feminine tenderness he was distinguished by the exceptional heart of a revolutionary will able to fight to the last drop of blood in the name of what he considered to be right and true. His spiritual independence appeared already in his youth when he ventured more than once to defend his opinion against the incontestable authority of Bebel. His work amongst the youth and his struggle against the Hohenzollern military machine was marked by great courage. Finally he discovered his full measure when he raised his voice against the serried warmongering bourgeoisie and the treacherous social-democracy in the German Reichstag where the whole atmosphere was saturated with miasmas of chauvinism. He discovered the full measure of his personality when as a soldier he raised the banner of open insurrection against the bourgeoisie and its militarism on Berlin’s Potsdam Square. Liebknecht was arrested. Prison and hard labour did not break his spirit. He waited in his cell and predicted with certainty. Freed by the revolution in November last year, Liebknecht at once stood at the head of the best and most determined elements of the German working class. Spartacus found himself in the ranks of the Spartacists and perished with their banner in his hands.

Rosa Luxemburg’s name is less well-known in other countries than it is to us in Russia. But one can say with all certainty that she was in no way a lesser figure than Karl Liebknecht. Short in height, frail, sick, with a streak of nobility in her face, beautiful eyes and a radiant mind she struck one with the bravery of her thought. She had mastered the Marxist method like the organs of her body. One could say that Marxism ran in her blood stream.

I have said that these two leaders, so different in nature, complemented each other. I would like to emphasize and explain this. If the intransigent revolutionary Liebknecht was characterized by a feminine tenderness in his personal ways then this frail woman was characterized by a masculine strength of thought. Ferdinand Lassalle once spoke of the physical strength of thought, of the commanding power of its tension when it seemingly overcomes material obstacles in its path. That is just the impression you received talking to Rosa, reading her articles or listening to her when she spoke from the tribune against her enemies. And she had many enemies! I remember how, at a congress at Jena I think, her high voice, taut like a wire, cut through the wild protestations of opportunists from Bavaria, Baden and elsewhere. How they hated her! And how she despised them! Small and fragilely built she mounted the platform of the congress as the personification of the proletarian revolution. By the force of her logic and the power of her sarcasm she silenced her most avowed opponents. Rosa knew how to hate the enemies of the proletariat and just because of this she knew how to arouse their hatred for her. She had been identified by them early on.

From the first day, or rather from the first hour of the war, Rosa Luxemburg launched a campaign against chauvinism, against patriotic lechery, against the wavering of Kautsky and Haase and against the centrists’ formlessness; for the revolutionary independence of the proletariat, for internationalism and for the proletarian revolution.

Yes, they complemented one another!

By the force of the strength of her theoretical thought and her ability to generalize Rosa Luxemburg was a whole head above not only her opponents but also her comrades. She was a woman of genius. Her style, tense, precise, brilliant and merciless, will remain for ever a true mirror of her thought.

Liebknecht was not a theoretician. He was a man of direct action. Impulsive and passionate by nature, he possessed an exceptional political intuition, a fine awareness of the masses and of the situation and finally an unrivalled courage of revolutionary initiative.

An analysis of the internal and international situation in which Germany found herself after November 9, 1918, as well as a revolutionary prognosis could and had to be expected first of all from Rosa Luxemburg. A summons to immediate action and, at a given moment, to armed uprising would most probably come from Liebknecht. They, these two fighters, could not have complemented each other better.

Scarcely had Luxemburg and Liebknecht left prison when they took each other hand in hand, this inexhaustible revolutionary man and this intransigent revolutionary woman and set out together at the head of the best elements of the German working class to meet the new battles and trials of the proletarian revolution. And on the first steps along this road a treacherous blow has on one day, struck both of them down.

To be sure reaction could not have chosen more illustrious victims. What a sure blow! And small wonder! Reaction and revolution knew each other well as in this case reaction was personified in the guise of the former leaders of the former party of the working class, Scheidemann and Ebert whose names will be for ever inscribed in the black book of history as the shameful names of the chief organizers of this treacherous murder.

It is true that we have received the official German report which depicts the murder of Liebknecht and Luxemburg as a street “misunderstanding” occasioned possibly by a watchman’s insufficient vigilance in the face of a frenzied crowd. A judicial investigation has been arranged to this end. But you and I know too well how reaction lays on this sort of spontaneous outrage against revolutionary leaders; we well remember the July days that we lived through here within the walls of Petrograd, we remember too well how the Black Hundred bands, summoned by Kerensky and Tsereteli to the fight against the Bolsheviks, systematically terrorized the workers, massacred their leaders and set upon individual workers in the streets. The name of the worker Voinov, killed in the course of a “misunderstanding” will be remembered by the majority of you. If we had saved Lenin at that time then it was only because he did not fall into the hands of frenzied Black Hundred bands. At that time there were well-meaning people amongst the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries who were disturbed by the fact that Lenin and Zinoviev, who were accused of being German spies, did not appear in court to refute the slander. They were blamed for this especially. But at what court? At that court along the road to which Lenin would be forced to “flee”, as Liebknecht was, and if Lenin was shot or stabbed, the official report by Kerensky and Tsereteli would state that the leader of the Bolsheviks was killed by the guard while attempting to escape. No, after the terrible experience in Berlin we have ten times more reason to be satisfied that Lenin did not present himself to the phoney trial and yet more to violence without trial.

But Rosa and Karl did not go into hiding. The enemy’s hand grasped them firmly. And this hand choked them. What a blow! What grief! And what treachery! The best leaders of the German Communist Party are no more—our great comrades are no longer amongst the living. And their murderers stand under the banner of the Social-Democratic party having the brazenness to claim their birthright from no other than Karl Marx! “What a perversion! What a mockery!&#rdquo; Just think, comrades, that “Marxist” German Social-Democracy, mother of the working class from the first days of the war, which supported the unbridled German militarism in the days of the rout of Belgium and the seizure of the northern provinces of France; that party which betrayed the October Revolution to German militarism during the Brest peace; that is the party whose leaders, Scheidemann and Ebert, now organize black bands to murder the heroes of the International, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg!

What a monstrous historical perversion! Glancing back through the ages you can find a certain parallel with the historical destiny of Christianity. The evangelical teaching of the slaves, fishermen, toilers, the oppressed and all those crushed to the ground by slave society, this poor people’s doctrine which had arisen historically was then seized upon by the monopolists of wealth, the kings, aristocrats, archbishops, usurers, patriarchs, bankers and the Pope of Rome, and it became a cover for their crimes. No, there is no doubt however, that between the teaching of primitive Christianity as it emerged from the consciousness of the plebeians and the official catholicism or orthodoxy, there still does not exist that gulf as there is between Marx’s teaching which is the nub of revolutionary thinking and revolutionary will and those contemptible left-overs of bourgeois ideas which the Scheidemanns and Eberts of all countries live by and peddle. Through the intermediary of the leaders of social-democracy the bourgeoisie has made an attempt to plunder the spiritual possessions of the proletariat and to cover up its banditry with the banner of Marxism. But it must be hoped, comrades, that this foul crime will be the last to be charged to the Scheidemanns and the Eberts. The proletariat of Germany has suffered a great deal at the hands of those who have been placed at its head; but this fact will not pass without trace. The blood of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg cries out. This blood will force the pavements of Berlin and the stones of that very Potsdam Square on which Liebknecht first raised the banner of insurrection against war and capital to speak up. And one day sooner or later barricades will be erected out of these stones on the streets of Berlin against the servile grovellers and running dogs of bourgeois society, against the Scheidemanns and the Eberts!

In Berlin the butchers have now crushed the Spartacists’ movement: the German communists. They have killed the two finest inspirers of this movement and today they are maybe celebrating a victory. But there is no real victory here because there has not been yet a straight, open and full fight; there has not yet been an uprising of the German proletariat in the name of the conquest of political power. There has been only a mighty reconnoitering, a deep intelligence mission into the camp of the enemy’s dispositions. The scouting precedes the conflict but it is still not the conflict. This thorough scouting has been necessary for the German proletariat as it was necessary for us in the July days.

The misfortune is that two of the best commanders have fallen in the scouting expedition. This is a cruel loss but it is not a defeat. The battle is still ahead.

The meaning of what is happening in Germany will be better understood if we look back at our own yesterday. You remember the course of events and their internal logic. At the end of February, the popular masses threw out the Tsarist throne. In the first weeks the feeling was as if the main task had been already accomplished. New men who came forward from the opposition parties and who had never held power here took advantage at first of the trust or half-trust of the popular masses. But this trust soon began to break to splinters. Petrograd found itself in the second stage of the resolution at its head as indeed it had to be. In July as in February it was the vanguard of the revolution which had gone out far in front. But this vanguard which had summoned the popular masses to open struggle against the bourgeoisie and the compromisers, paid a heavy price for the deep reconnaissance it carried out.

In the July Days the Petrograd vanguard broke from Kerensky’s government. This was not yet an insurrection as we carried through in October. This was a vanguard clash whose historical meaning the broad masses in the provinces still did not appreciate. In this collision the workers of Petrograd revealed before the popular masses not only of Russia but of all countries that behind Kerensky there was no independent army, and that those forces which stood behind him were the forces of the bourgeoisie, the white guard, the counter-revolution.

Then in July we suffered a defeat. Comrade Lenin had to go into hiding. Some of us landed in prison. Our papers were suppressed. The Petrograd Soviet was clamped down. The party and Soviet printshops were wrecked, everywhere the revelry of the Black Hundreds reigned. In other words there took place the same as what is taking place now in the streets of Berlin. Nevertheless none of the genuine revolutionaries had at that time any shadow of doubt that the July Days were merely the prelude to our triumph.

A similar situation has developed in recent days in Germany too. As Petrograd had with us, Berlin has gone out ahead of the rest of the masses; as with us, all the enemies of the German proletariat howled: “we cannot remain under the dictatorship of Berlin; Spartacist Berlin is isolated; we must call a constituent assembly and move it from red Berlin—depraved by the propaganda of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg—to a healthier provincial city in Germany.” Everything that our enemies did to us, all that malicious agitation and all that vile slander which we heard here, all this translated into German was fabricated and spread round Germany directed against the Berlin proletariat and its leaders, Liebknecht and Luxemburg. To be sure the Berlin proletariat’s intelligence mission developed more broadly and deeply than it did with us in July, and that the victims and the losses are more considerable there is true. But this can be explained by the fact that the Germans were making history which we had made once already; their bourgeoisie and military machine had absorbed our July and October experience. And most important, class relations over there are incomparably more defined than here; the possessing classes incomparably more solid, more clever, more active and that means more merciless too.

Comrades, here there passed four months between the February revolution and the July days; the Petrograd proletariat needed a quarter of a year in order to feel the irresistible necessity to come out on the street and attempt to shake the columns on which Kerensky’s and Tsereteli’s temple of state rested. After the defeat of the July days, four months again passed during which the heavy reserve forces from the provinces drew themselves up behind Petrograd and we were able, with the certainty of victory, to declare a direct offensive against the bastions of private property in October 1917.

In Germany, where the first revolution which toppled the monarchy was played out only at the beginning of November, our July Days are already taking place at the beginning of January. Does this not signify that the German proletariat is living in its revolution according to a shortened calendar? Where we needed four months it needs two. And let us hope that this schedule will be kept up. Perhaps from the German July Days to the German October not four months will pass as with us, but less—possibly two months will turn out sufficient or even less. But however event proceed, one thing alone is beyond doubt: those shots which were sent into Karl Liebknecht’s back have resounded with a mighty echo throughout Germany. And this echo has rung a funeral note in the ears of the Scheidemanns and the Eberts, both in Germany and elsewhere.

So here then we have sung a requiem to Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The leaders have perished. We shall never again see them alive. But, comrades, how many of you have at any time seen them alive? A tiny minority. And yet during these last months and years Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg have lived constantly among us. At meetings and at congresses you have elected Karl Liebknecht honorary president. He himself has not been here—he did not manage to get to Russia—and all the same he was present in your midst, he sat at your table like an honoured guest, like your own kith and kin—for his name had become more than the mere title of a particular man, it had become for us the designation of all that is best, courageous and noble in the working class. When any one of us has to imagine a man selflessly devoted to the oppressed, tempered from head to foot, a man who never lowered his banner before the enemy, we at once name Karl Liebknecht. He has entered the consciousness and memory of the peoples as the heroism of action. In our enemies’ frenzied camp when militarism triumphant had trampled down and crushed everything, when everyone whose duty it was to protest fell silent, when it seemed there was nowhere a breathing-space, he, Karl Liebknecht, raised his fighter’s voice. He said “You, ruling tyrants, military butchers, plunderers, you, toadying lackies, compromisers, you trample on Belgium, you terrorize France, you want to crush the whole world, and you think that you cannot be called to justice, but I declare to you: we, the few, are not afraid of you, we are declaring war on you and having aroused the masses we shall carry through this war to the end!” Here is that valour of determination, here is that heroism of action which makes the figure of Liebknecht unforgettable to the world proletariat.

And at his side stands Rosa, a warrior of the world proletariat equal to him in spirit. Their tragic death at their combat positions couples their names with a special, eternally unbreakable link. Henceforth they will be always named together: Karl and Rosa, Liebknecht and Luxemburg!

Do you know what the legends about saints and their eternal lives are based upon? On the need of the people to preserve the memory of those who stood at their head and who guided them in one way or another; on the striving to immortalize the personality of the leaders with the halo of sanctity. We, comrades, have no need of legends, nor do we need to transform our heroes into saints. The reality in which we are living now is sufficient for us, because this reality is in itself legendary. It is awakening miraculous forces in the spirit of the masses and their leaders, it is creating magnificent figures who tower over all humanity.

Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg are such eternal figures. We are aware of their presence amongst us with a striking, almost physical immediacy. At this tragic hour we are joined in spirit with the best workers of Germany and the whole world who have received this news with sorrow and mourning. Here we experience the sharpness and bitterness of the blow equally with our German brothers. We are internationalists in our sorrow and mourning just as much as we are in all our struggles.

For us Liebknecht was not just a German leader. For us Rosa Luxemburg was not just a Polish socialist who stood at the head of the German workers. No, they are both kindred of the world proletariat and we are all tied to them with an indissoluble spiritual link. Till their last breath they belonged not to a nation but to the International!

For the information of Russian working men and women it must be said that Liebknecht and Luxemburg stood especially close to the Russian revolutionary proletariat and in its most difficult times at that. Liebknecht’s flat was the headquarters of the Russian exiles in Berlin. When we had to raise the voice of protest in the German parliament or the German press against those services which the German rulers were affording Russian reaction we above all turned to Karl Liebknecht and he knocked at all the doors and on all the skulls, including the skulls of Scheidemann and Ebert to force them to protest against the crimes of the German government. And we constantly turned to Liebknecht when any of our comrades needed material support. Liebknecht was tireless as the Red Cross of the Russian revolution.

At the congress of German Social-Democrats at Jena which I have already referred to, where I was present as a visitor, I was invited by the presidium on Liebknecht’s intiative to speak on the resolution moved by the same Liebknecht condemning the violence and the brutality of the Tsarist government in Finland. With the greatest diligence Liebknecht prepared his own speech collecting facts and figures and questioning me in detail on the customs relations between Tsarist Russia and Finland. But before the matter reached the platform (I was to speak after Liebknecht) a telegram report on the assassination of Stolypin in Kiev had been received. This telegram produced a great impression at the congress. The first question which arose amongst the leadership was: would it be appropriate for a Russian revolutionary to address a German congress at the same time as some other Russian revolutionary had carried out the assassination of the Russian Prime Minister? This thought seized even Bebel: the old man who stood three heads above the other Central Committee members, did not like any “needless” complications. He at once sought me out and subjected me to questions: “What does the assassination signify? Which party could be responsible for it? Didn’t I think that in these conditions that by speaking I would attract the attention of the German police?” “Are you afraid that my speech will create certain difficulties?” I asked the old man cautiously. “Yes”, answered Bebel, “I admit I would prefer it if you did not speak.” “Of course,” I answered, “in that case there can be no question of my speaking.” And on that we parted.

A minute later, Liebknecht literally came running up to me. He was agitated beyond measure. “Is it true that they have proposed you do not speak?” he asked me. “Yes,” I replied, “I have just settled this matter with Bebel.” “And you agreed?” “How could I not agree,” I answered justifying myself, “seeing that I am not master here but a visitor.” “This is an outrageous act by our presidium, disgusting, an unheard-of scandal, miserable cowardice!” etc., etc. Liebknecht gave vent to his indignation in his speech where he mercilessly attacked the Tsarist government in defiance of backstage warnings by the presidium who had urged him not to create “needless” complications in the form of offending his Tsarist majesty.

From the years of her youth Rosa Luxemburg stood at the head of those Polish Social-Democrats who now together with the so-called “Lewica” i.e. the revolutionary Section of the Polish Socialist Party have joined to form the Communist Party. Rosa Luxemburg could speak Russian beautifully, knew Russian literature profoundly, followed Russian political life day by day, was joined by close ties to the Russian revolutionaries and painstakingly elucidated the revolutionary steps of the Russian proletariat in the German press. In her second homeland, Germany, Rosa Luxemburg with her characteristic talent, mastered to perfection not only the German language but also a total understanding of German political life and occupied one of the most prominent places in the old Bebelite Social-Democratic party. There she constantly remained on the extreme left wing.

In 1905 Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg in the most genuine sense of the word lived through the events of the Russian revolution. In 1905 Rosa Luxemburg left Berlin for Warsaw, not as a Pole but as a revolutionary. Released from the citadel of Warsaw on bail she arrived illegally in Petrograd in 1906, where, under an assumed name, she visited several of her friends in prison. Returning to Berlin she redoubled the struggle against opportunism opposing it with the path and methods of the Russian revolution.

Together with Rosa we have lived through the greatest misfortune which has broken on the working class. I am speaking of the shameful bankruptcy of the Second International in August 1914. Together with her we raised the banner of the Third International. And now, comrades, in the work which we are carrying out day in and day out we remain true to the behests of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. If we build here in the still cold and hungry Petrograd the edifice of the socialist state, we are acting in the spirit of Liebknecht and Luxemburg; if our army advances on the front, it is defending with blood the behests of Liebknecht and Luxemburg. How bitter it is that it could not defend them too!

In Germany there is no Red Army as the power there is still in enemy hands. We now have an army and it is growing and becoming stronger. And in anticipation of when the army of the German proletariat will close its ranks under the banner of Karl and Rosa, each of us will consider it his duty to draw to the attention of our Red Army, who Liebknecht and Luxemburg were, what they died for and why their memory must remain sacred for every Red soldier and for every worker and peasant.

The blow inflicted on us is unbearably heavy. Yet we look ahead not only with hope but also with certainty. Despite the fact that in Germany today there flows a tide of reaction we do not for a minute lose our confidence that there, red October is nigh. The great fighters have not perished in vain. Their death will be avenged. Their shades will receive their due. In addressing their dear shades we can say: “Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, you are no longer in the circle of the living but you are present amongst us; we sense your mighty spirit; we will fight under your banner; our fighting ranks shall be covered by your moral grandeur! And each of us swears if the hour comes, and if the revolution demands, to perish without trembling under the same banner as under which you perished, friends and comrades-in-arms, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht!”

Archives, 1919

0 Comments: