When The World, Our World,

Was Young- The Night of The Howl

From The Pen Of Frank Jackman

From The Pen Of Frank Jackman

Several

years ago when the literary world, and not just the literary world, was

commemorating the 50th anniversary of the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road there were a plethora of books and articles

about the meaning of it all, about the place of the book, and of the author, in

the American literary pantheon. Any number of writers, who knew, or maybe had

been influenced by Kerouac chimed in about subjects related to the book from

the origins of each individual episode in that “beat” travelogue to the various

literary tropes that Jack used in his writing (you know “the holy fool,” the

goof, the zen master wisdom king, Catholic notions of salvation, urban rootlessness,

perennial wanderlust, and so on). Others took a different tact and spoke to the

meaning of the book for their psychological well-being by having emulated the

trappings of what Sal/Jack, Dean/Neal, Irwin/Allen, Bull/William did, or did

not, do for them on their individual searches for the blue-pink great American

West night. Took time to express what being on the open road the first time,

smoking their first dope smoke, having their first bouts with loose sex meant.

Maybe telling about the travails of the road too, the dusty back road bus

stations, sleeping out along the side of some wayward Iowa cornfield waiting

for dawn to start again on the hitchhike road, being left off in the middle of

nowhere by some trucker who was heading south when you were heading west, the

endlessly poor diet either from on the run quick meal foods to truckers’ diner

fare. All taken in stride, all missed, all nostalgia missed, wouldn’t it be

great to do again except now I have that house, that spouse, those kids, that

looming college tuition crisis to content with and so the search for that

American night dropped off the radar.

Others

rather than writing about what On The

Road meant personally, socially, as literature wrote their own quirky

little pieces that reflected the heat from Jack’s sun. One such writer, or

rather a guy who liked to write since his main professions in life were

elsewhere, was Peter Paul Markin who wrote his own version of the beat

travelogue to the tune of his generation, the generation after Kerouac’s

“beats,” the generation of ‘68, the

“hippies” to give them a known name if not entirely accurate to describe the

whole scene just as “beat” does not reflect that whole of that previous scene, obviously

influenced by Kerouac entitled Ancient

dreams, dreamed which met with some small success in 2009. In order to

commemorate the 5th anniversary of the publication of that effort,

that series of sketches as Markin himself put it I here will give forth to all

and sundry on the real meaning or that short work:

It is hard

to not be overcome by the hard fact that Peter Paul Markin’s (hereafter Markin) efforts to try to find

some life lessons in Ancient dreams,

dreamed were driven by sex, or

really what to do about the opposite sex in his life. We can all use a primer, any

help at all, male or female, in that struggle but one should be first be struck

by how early on that male-female thing as the core of existence played a role in his sketches.

For example in the very first sketch Markin goes on and on about a certain Miss

Cora from the film noir The Postman

Always Rings Twice who twisted a drifter named Frank around her finger so

bad he couldn’t see straight, went to his big step-off with a smile after he

amateurishly helped her get rid of her low-rent, no go husband and botched it

as bad as a man could, no, went to that big step-off after she set him up for

the fall all by his lonesome with a half-smile on his face (Jesus, Markin has

got me going now with that smile/ half-smile bull he kept yakking about). He

absorbed those lessons unto he fifth degree. But get this he, Markin claims,

claims as he said this to me on a stack of bibles or something that he had

“seen” the movie while in his mother’s womb and tried to warn Frank off Miss

Cora. Claims that in 1946 he learned all there was to learn about woman and

their wanting habits by just “seeing” that film. Hey, rather than me getting

all cranky and upset about being put on by him let Frank tell it his way, or

the way he had his narrator tell it since that guy knew Frank before the end

and you can decide:

Yah,

sometimes, and maybe more than sometimes, a frail, a frill, a twist, a dame, oh

hell, let’s cut out the goofy stuff and just call her a woman. That frail,

frill business a throwback to my spending too much time in childhood reading

those serious crime novels by the likes of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond

Chandler all curled up in some bed at night wondering, wondering in silence

whether I had the stuff, the stuff of dreams. Maybe watching too many Saturday

matinee 1930s gangster and slick Sam Spade hard-boiled detective movies at the

revival Strand Theater where I used to sneak into from the back door up into

the balcony. Wondering watching those

films whether I was going to be another joe on that lost highway Hank always

talked about, just a guy who kept his nose clean and didn’t make waves. Well I

sure as hell did make some waves and have paid the price but that is my story.

Today I’ve got Frank’s story to tell, my buddy Frank Dawson who I met in here

and was as white a guy as you could ever meet, except when he got on the scent

of a woman. At least that is how the newspapers told the story before he told

it to me nice and personal, the real story, that perfume scent that drove him

over the edge.

See Frank,

when it came right down to it was no different from me, maybe that’s why we got

along alright in tight quarters, because he wanted to make a big splash, make

waves unlike his old man who drained his life away working some dustbowl farm.

Well Frank sure as hell did. Except for me it was always about the business

first, you know getting a haul from some sweet virgin bank where all the kale,

you know dough, was stashed away just waiting for guys like me to pounce on it.

Frank whatever larceny he had in his heart though always mixed up that with

some woman thing, some scent of a woman thing that will tie a guy’s insides up

in knots so bad he doesn’t know what is what. Tied a guy up, a guy like Frank

Dawson, a rolling stone from out in the sticks somewhere who headed, or maybe

landed is better here in California and really thought he was going to make the

garden of Eden out of his small life. Like I said he got twisted so bad, so bad

that like some other guys I knew, not good guys like Frank but some mean

bracero hombres who would cut you up with some hidden “shiv,” a blade, as easy

as look at you, that he went to the chair without a murmur, the electric chair

for those not in the know or those not wound up in the love game with a big old

knot very tightly squeezing him. That is he would not murmur if there is such a

merciful chair in his locale, otherwise whatever way they cut the life out of a

guy who has been so twisted up he couldn’t think straight enough to tie his own

shoes, or hers.

Here’s the

funny part and you know as well as I do that I do not mean funny, laughing funny,

Frank went to his great big reward smiling, okay half-smiling, just to have

been around that frail, frill, twist, dame, oh hell, you know what I mean.

Around her slightly shy, sly, come hither scents, around her, well, just around

her. Or maybe just to be done with it, done with the speculation, the knots and

all, six-two-and even he would go back for more, plenty more, and still have

that smile, ah, half-smile as they led him away. Yah, guys just like Frank. Let

me explain what I mean, okay.

Frank Dawson

had it bad. [But you might as well fill in future signatures, the Peter Paul

Markins, the Joshua Lawrence Breslins, guys who I hung around with and had

dough dreams too, and every corner boy who ever kicked his heels against some

drugstore store front wall, name your name, just kids, mere boys, when they

started getting twisted up in knots, girl knots, and a million, more or less,

other guys too, just as easily as Frank, real easy]. Yah, Frank had it as bad

as a man could have from the minute Miss Cora walked through that café door.

(He always called her Miss Cora although she was married, married as could be,

I wonder if he called her Miss Cora when they were under the satin sheets naked

as jaybirds and her showing him a trick or two to curl his toes, I never asked

him though). That café door was the entrance from the back of the house, the

door that separated the living quarters from the café, hell greasy spoon, a cup

of joe in her hand. Frank said he vividly remembered just an off-hand plain

plank door, cheaply made and amateurishly hinged, that spoke of no returns. That

no returns is what I said after I heard the story and was writing stuff down

like he asked me to when he wanted the world to know what really happened along

the way to the big step-off. He never said such stuff, never put an evil,

fateful, spin on things even toward the end. Even when he was ready to meet his

maker. Damn.

She breezed

in, breezed in like some trade winds, all sugary and sultry, Frank thought

later when he tried to explain it to his lawyer, to the judge, to the jury, to

some newspaper guy they let interview him who balled the whole thing up , yeah,

even to the priest, a Catholic priest, Father Riley, although Frank said he was

brought up a pre-destined Baptist and didn’t know half the stuff the priest had

been talking about like penance and revelation, who visited him every day

toward the end, and to me at night when the lights were out and we would talk

and he wanted somebody, a guy like him, to know what drove him and why.

Yeah so he

would try to explain everything that had happened and how to anyone who would

listen about her breezing in, trade winds breezed he said having once in the

service been down in Puerto Rico for bomb practice when he was on a Navy ship although

this was the wrong coast for that kind of wind but I got what he meant, had had

a couple of breezes like that myself but I like I said I didn’t mix business

with pleasure. Made that a rule early on when I almost got clipped by a woman

who had big wanting habits, I was daffy about, she tried to make me press my

luck by trying to pull another robbery of the same place which was insane so

she and I could go to Europe, or something like that. It was only by the skin

of our necks that we pulled the job off but one of the guys on the job with got

sent to the pearly gates when the security guard figured out quicker than the

first time that the joint was going to be hit, hit hard and sang his

rooty-toot-toot song. After that never again.

So there she

was in her white summer frilly V-neck buttoned cotton blouse, white short

shorts, tennis or beach ready, maybe just ready for whatever came along, with

convenience pockets for a woman’s this-and-that, and showing plenty of

well-turned, lightly-tanned bare leg, long legs at first glance, and the then de rigueur bandana holding back her

hair, also white, the bandana that is. Yah, she came out of that crooked

cheapjack door like some ill-favored Pacific wind now that Frank had the coast

right, some Japan Current ready, ready for the next guy out. Jesus even I got

weepy when he said that.

I might as

well tell you, just like he told it to me, incessantly told it to me toward the

end like I was some father-confessor, and maybe I was, a real father confessor

being a few years older, having been here longer, and not talking about penance

and salvation but just trying to keep the story straight, before he moved on,

it didn’t have to finish up like the way it did. Or start that way either, for

that matter. The way it did play out. Not at all. No way. Frank could have just

turned around anytime he said but I just took that as so much wind talking, or

maybe some too late regret. I know and you now will know how I know that he

would call out her name at night, maybe a two o’clock when it was real dark and

the turnkey was off in the guard room sleeping some drunk off, call out her

name and, giggly like a schoolboy, telling her to stop this and stop that,

giggly like I said, and then called her sweetly, like she was some girl next door

virgin all pure and all, his sweet baby whore. Yeah, now that I think about it

he was blowing wind, maybe that trade wind stuff all sugary and sultry. Sure

there are always choices, for some people. Unless you had some

Catholic/Calvinist/Shiva whirl pre-destination Mandela wheel working your

fates, working your fates into damn overdrive like our boy Frank.

Listen up a

little and see if you think Frank was just blowing smoke, or something. He was

just a half-hobo, maybe less, bumming around and stumbling up and down the West

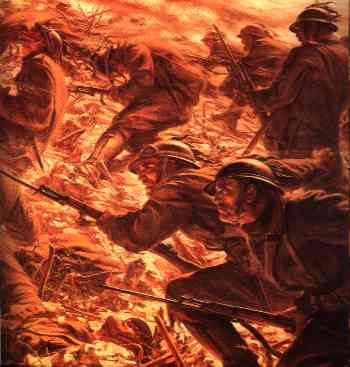

Coast, too itchy to settle down after four years of hard World War II Pacific

battle fights on bloody atolls, on bloody coral reefs, and knee-deep bloody

islands with names even he couldn’t remember, or want to remember after Cora came

on the horizon. (A lot of guys after the

war had a hard time settling down just drifting around, coming out here from

the East looking for something, finding land’s end and I don’t know surf

boards, or hot rods, or drug smuggling I don’t know since I was born here and

like I said my trade was robbing banks where the dough was, that was my kicks) He

was just stumbling, like he said, from one half-ass mechanic’s job (a skill he

had picked in the Marines working on everything from a bicycle to a battleship

he would laugh) in some flop garage for a week here when the regular guy was on

vacation or something, drifting, another city day laborer’s job shoveling

something there, and picking fruits, hot sun fruits, maybe vegetables depending

on the crop rotation, like some bracero whenever things got really tough, or

the hobo jungle welcome ran out, ran out with the running out of wines and

stubbed cigarette butts. He mentioned something about freight yard tramp

knives, and cuts and wounds. Tough, no holds barred stuff, once tramp, bum,

hobo solidarities broke down, and that easy and often. Frank just kind of

flashed by me that part of the story because he was in a hurry for me to get it

straight about him and Cora and the hobo jungle stuff was just stuff, and so much

train smoke and maybe a bad dream.

Guys would

show up later at trial trying to get in on the action and claim that they saw

Frank cut a guy, maybe more than one guy, you never know with winos and

jack-rollers, and leave him, or them, for dead but the deeds never involved

women so I agreed with Frank they were just conning for something. The judge

never let them get too far before tossing them off the stand. The prosecution

was just pig-piling the evidence to see what would stick with the jury to show Frank

was some hardened criminal from the get-go not a love-bit guy or just another

hard luck story out of the Great Depression times.

Hell, the

way he was going, after some bracero fruit days with some bad hombre gringo ass

bosses standing over his sweat, the “skids” in Los Angeles, down by the tar

pits and just off the old Southern Pacific line, were looking good, a good rest

up. Real good after fourteen days running in some Imperial Valley fruit fields

so he started heading south, south by the sea somewhere near Paseo Robles to

catch some ocean sniff, and have himself washed clean by loud ocean sounds so

he didn’t have to listen to the sounds coming from his head about getting off

the road.

Here is

where luck is kind of funny though, and maybe this is a place where it is

laughing funny, because, for once, he had a few bucks, a few bracero fruit

bucks, stuck in his socks. He was hungry, maybe not really food hungry, but

that would do at the time for a reason, and once he hit the coast highway this Bayview

Diner was staring him right in the face after the last truck ride had let him

off a few hundred yards up the road. Some fugitive barbecued beef smell, or

maybe strong onions getting a workout over some griddled stove top, reached him

and turned him away from the gas station fill-up counter where he had planned,

carefully planning to husband his dough to make the city of angels, to just

fill up with a Coke and a moon pie. Instead he just grabbed a pack of Luckies,

unfiltered cigarettes but a step up from the rolling Bull Durham that he had

survived on before he got paid off on that bracero labor job and headed toward

the café. That smell just got the better of him. So he walked into that Bayview Diner, walked

in with his eyes wide open. And then she walked through the damn cheapjack door.

She may have

been just another blonde, a very blonde frail, maybe with a slight pair of

round heels and heading toward a robust thirty or so just serving them off the

arm in some seaside hash joint along with her husband as he found out a few

minutes later, too late, but from second one when his eyes eyed her she was

nothing but, well nothing but, a femme

fatale. Frank femme fatale,

fatal. Of course between eyeing, pillow-talk dreaming, and scheming up some

“come on” line once she had her hooks into him, which was about thirty seconds

after he laid eyes on her, he forgot, foolishly forgot, rule number one of the

road, or even of being a man in go-go post-war America.

What he

should have asked, and had in the past when he wasn’t this dame-addled, was a

dish like this doing serving them off the arm in some rundown roadside café out

in pacific coast Podunk, really just south of Santa Barbara, when she could be

sunning herself in some be-bop daddy paid-up hillside bungalow or scratching

some other dame’s eyes out to get a plum role in a B Hollywood film courtesy of

some lonely rich producer. Never for a minute, not even during those thirty

seconds that he wasn’t hooked did he figure, like some cagey guy would figure,

that she had a story hanging behind that bandana hair.

And she did.

Story number one was the “serve them off the platter” hubby, Manny,

short-ordering behind the grill in that tramp cafe. The guy who, to save dough,

bought some wood down at the lumber yard and put up that crooked door that she

had come through on first sight and who spent half his waking hours trying to

figure how to short-change somebody, including his Cora. Wouldn’t buy her the

trinkets that every woman loved so she, since he could hardly add for all his

cheapness and she handled the books, just took what she wanted when she wanted

it and he was never the wiser. (Guys, including Manny were like that with Cora,

will always be like that with the Coras of the world so Frank wasn’t alone he

just got skirt-addled more than most guys who maybe had better radar to avoid

that trouble coming through the door.) Story

number two, and go figure, said hubby

didn’t care one way or the other about what she did, or didn’t do, as long as

he had her around as a trophy to show the boys on card-playing in the back of

the diner living rooms and Kiwanis Club down the road drunk as a skunk nights. She

loathed Manny at those times, times when to get a laugh for the boys, maybe

inflame them too, he would paw her like some dumb pet. Story number three was

that she had many round-heeled down-at- the-heels stories too long to tell

Frank before hubby came along to pick her out of some Los Angles arroyo gutter.

Doped up to stop the pain of her life, tricked up to pay for the dope, and none

too choosey about who did what to her as long as they brought a needle and a

spoon. And they did until she crossed some low-life in Westminster and he threw

her out to beg for herself. Story number four, the one that would in the end

sent our boy Frankie smiling, sorry half-smiling, to his fate was she hated

hubby, hell-broth murder hated her husband, and would be “grateful” in the

right way to some guy who had the chutzpah to take her out of this misery. But

those stories all came later, later when she didn’t need to use those hooks she

had in him, didn’t need to use them at all.

Markin

Interlude One: “I swear, I swear on

seven sealed bibles that I yelled, yelled from some womblike place, at the

screen in the old Orpheum Theater up in Adamsville Square when my mother was

“carrying” me once I saw her coming through that door for him, for Frank, to get the hell out of there at that moment. I

saw that come hither look that is embedded in their womanly DNA she threw at

him and I saw him buckle, buckle under foot, with his eyes all glued to her

walk also embedded in his manly DNA (what did we know of such things, embedded

or not, then Frank just called it a breeze, some kind of breeze like he could

have stopped the thing in its tracks).This dame was poison, no question. Frank

stop looking at those long paid for legs and languid rented eyes for a minute,

forget about ocean breezes or desert-addled and get the hell out of there to

some safe hobo jungle. Hell, just walk out the diner, café or whatever it is

door, run if you have to, get your hitchhike great blue-pink American West

thumb out and head for it. There’s a hobo jungle just down the road near Santa

Monica, get going, and tonight grab some stolid, fetid stews, and peace.”

But here is

where fate works against some guys, hell, most guys. She turned around to do

some dish rack thing or other with her lipstick-smeared coffee cup and then,

slowly, turned back to look at Frank with those languid eyes, what color who knows, it was the look

not the color that doomed Frank and asked in a soft, kittenish voice “Got a cigarette for a fresh out girl?” And

wouldn’t you know, wouldn’t you just know that Frank, “flush” with bracero

dough had bought that fresh deck of

Luckies at the cigarette machine out at that filling station just adjacent to

the diner and they were sitting right in his left shirt pocket for the entire

world to see. For her to see. And wouldn’t you know too that Frank could see

plain as day, plain as a man could see if he wanted to see, that bulging out of

one of the convenient pockets of those long-legged white short shorts was the

sharply-etched outline of a package of cigarettes. Yah, still he plucked a Lucky

cigarette into her waiting lips, kind of gently, gently for rough-edged Frank,

lit her up, and dated her up with his eyes. Gone, long-gone daddy gone, except

for two in the morning murmur dreams, and that final half-smile.

Peter Paul

Markin Interlude Two: “I screamed again, some vapid man-child scream, some

kicking at the womb thump too, but do you think Frank would listen, no not our

boy. You don’t need to know all the details if you are over twenty-one, hell

over twelve and can keep a secret. She used her sex every way she could, and a

few ways that Frank, not unfamiliar with the world’s whorehouses in lonely

ports-of-call, was kind of shocked at, but only shocked. He was hooked, hook,

line and sinker. Frank knew, knew what she was, knew what she wanted, and knew

what he wanted so there was no crying there.”

Here is what

is strange, and while I am writing this even I think it is strange. She told

Frank her whole life’s story, the too familiar father crawling up into her

barely teenage bed, the run-aways, returns, girls’ JD homes, some more streets,

a few whorehouse tricks, some street tricks, a little luck with a Hollywood

producer until his wife, who controlled the dough, put a stop to it, some

drugs, some L.A. gutters, and then a couple of years back some refuge from

those mean streets via husband Manny’s Bayview Diner.

Even with

all of that Frank still believed, believed somewhere from deep in his recessed

mind, somewhere in his Oklahoma kid mud shack mind, that Cora was virginal.

Some Madonna of the streets. Toward the end it was her scent, some slightly lilac

scent, some lilac scent that combined with steamed vegetable sweat combined

with sexual animal sweat combined with ancient Lydia MacAdams' bath soap fresh

junior high school “crush” sweat drove him over the edge. Drove him to that

smiling chair.

He had to

play with fire, and play with it to the end. Christ, just like his whole young

stupid gummed up life he had to play with fire. And from that minute, the lit

cigarette minute, although really from the minute that Frank saw those long

legs protruding from those white shorts Manny was done for. And once Frank had

sealed his fate (and hers too) on that midnight

roaring rock sandy beach night when the ocean depths smashing against

the shore drowned out the sound of their passion everybody from Monterrey to

Santa Monica knew he was done for, or said they knew the score after the fact.

Everybody who came within a mile of the Bayview Diner anyway. Everybody except

Manny and maybe somewhere in his cheap- jack little heart he too knew he was

done for when Cora, in her own sensible Cora way, persuaded him that he needed

an A-One grease monkey to run the filling station.

The way

Frank told it even I knew, knew that everybody had to have figured things out.

Any itinerant trucker who went out of his way to take the Coast highway with

his goods on board in order to get a

full glance at Cora and try his “line” on her knew it (Manny encouraged it, he

said it was good for business and harmless, and maybe it was with them). Knew

it the minute he sat at his favorite corner stool and saw a monkey

wrench-toting Frank come in for something and watch the Frank-Cora- and

cigar-chomping Manny in his whites behind the grille dance play out. He kept

his eyes and his line to himself on that run.

Damn, any

dated –up teen-age joy-riding kids up from Malibu looking for the perfect wave

at Roaring Rock (and maybe some midnight passion drowned out by the ocean roar

too) knew the minute they came in and smelled that lilac something coming like

something out of the eden garden from Cora. The girls knowing instinctively

that Cora lilac scent was meant for more than some half-drunk old short order

cook. One girl, with a friendly look Frank’s way, and maybe with her own Frank

Roaring Rock thoughts, asked Cora, while ordering a Coke and hamburger, whether

she was married to him. And her date, blushing, not for what his date had just

said but because he, fully under the lilac scent karma, wished that he was

alone just then so he could take a shot at Cora himself.

Hell even

the California Highway Patrol motorcycle cop who cruised the coast near the

diner (and had his own not so secret eyes and desires for Cora) knew once Frank

was installed in one of the rooms over

the garage that things didn’t add up, add up to Manny’s benefit. And, more

importantly, that if anything happened, anything at all, anything requiring

more than a Band-Aid, to one Manny DeVito for the next fifty years the cops

knew the first door to knock at.

Look I am

strictly a money guy, going after loot wherever I could and so I never after

that one time early on got messed up with some screwy dame on a caper. That was

later, spending money time later. And maybe if I had gotten a whiff of that

perfume things might have been different in my mind too but I told Frank right

out why didn’t he and Cora take out a big old .44 in the middle of the diner

and just shoot Manny straight out, and maybe while the cop was present

too. Then he /they could have at least

put up an insanity or crime of passion defense. Not our boy though, no he had

to play the angles, play Cora’s evil game.

I am almost too

embarrassed, almost too embarrassed since Frank is not here to defend himself,

maybe he could have given us an inkling of what he was thinking about at the time,

if he was thinking of anything but those pillow dreams, to detail how badly these

two amateurs gummed up the job every which way. (I already know what she, Miss

Cora, was thinking, had her sized up the minute Frank mentioned who he was and

who she was, mentioned those white shorts and that short order husband). Yeah,

they gummed it up so that even a detective novel writer would turn blush red

with shame. Yeah somebody like Dashiell Hammett, a guy who knew how to plot out

the murders, how to raise holy hell in Red Harvest times would blush to think

that they could do the “perfect” murder with their skinny sense of how to do criminal

things. Hell, trying poison and the off the cliff with the car routine like a thousand

guys have done before-and always got caught. The old brakes giving out and over

the hill crashing and Frank an A-One mechanic even some silly skirt-addled highway

motorcycle cop could figure given some time.

I tried to

tell Frank this but he was only half-listening, only wanted to tell his story

mostly but I guess I am trying to make sense of the deal for anybody who might

read this, maybe wise you up if you are thinking about doing away some Manny or

other. Murder is, from guys that I know who specialize in such things, make a

business out of taking guys out for dough, an art form and nothing for amateurs

to mess around with. So they tried one thing, something with poison taken over

a long time that couldn’t be traced but Manny was such a lush it didn’t take.

Then another, they tried to get him drunk and drown him off of Roaring Rock but

that night around two in the morning about sixty kids from down around Malibu

decided to have a cook-out after their prom night. In the end they planned and wound

up with the old gag that the cops have been wise to since about 1906, got him

drunk, conked him, threw him in the car, drove to the Roaring Rock and pushed

him and the car over the cliff after Frank messed with the brakes. Jesus,

double jesus.

Peter Paul

Interlude Three: “Frank, one last time, get out, get on the road, this ain’t

gonna work. That poison thing was crazy. That drunk at the ocean thing was

worst. The cops wouldn’t even have had to bother to knock at your door. Frank

on this latest caper she’s setting you up. Think-who drove the car, who got the

whiskey at the liquor store down the road, who knew how to trip the brake lines,

and who was big enough to carry Manny? And

she sitting at home waiting for her husband and his mechanic to come home after

a toot. Why don’t you just paint a big target on your chest and be done with

it. She just wants the diner for her own small dreams. You don’t count. Hell, I

ain’t no squealer but she is probably talking to that skirt-crazy (her skirt)

cop right now. Get out I say, get out.”

If you want

the details, want to see how she framed him but good and walked away with half

the California legal system holding the door open for her, just look them up in

the 1946 fall editions of the Los Angeles

Gazette. They covered the story big time, and the trial too. See how on the

stand she lied her ass off about the child she was carrying being Manny’s and what

was she to do now with a child to bring up alone. Lied about how Frank made

advances toward her which she rebuffed. Even had a couple of Manny’s drinking

buddies get on the stand and tell how Manny encouraged them to go so far with

Miss Cora, pinching her behind, maybe a kiss on the cheek but Manny made very

clear no further. And Manny told them he told Frank that same thing. And the

most beautiful part of the whole thing, the thing that made Miss Cora a real femme fatale in my book was that the

whole affair at her urging was kept very secret no matter what customers, the

good old boy truckers, the young college kids might think so there was not tangible

evidence to proof they had been together all those weeks and months. That’s

just the details though. I can give you the finish, the last moments now and

save your eyes, maybe. Frank, yah, Frank was just kind of smiling that smile,

what did I call it, half-smile, all the way to the end. Do you need to know

more?