The

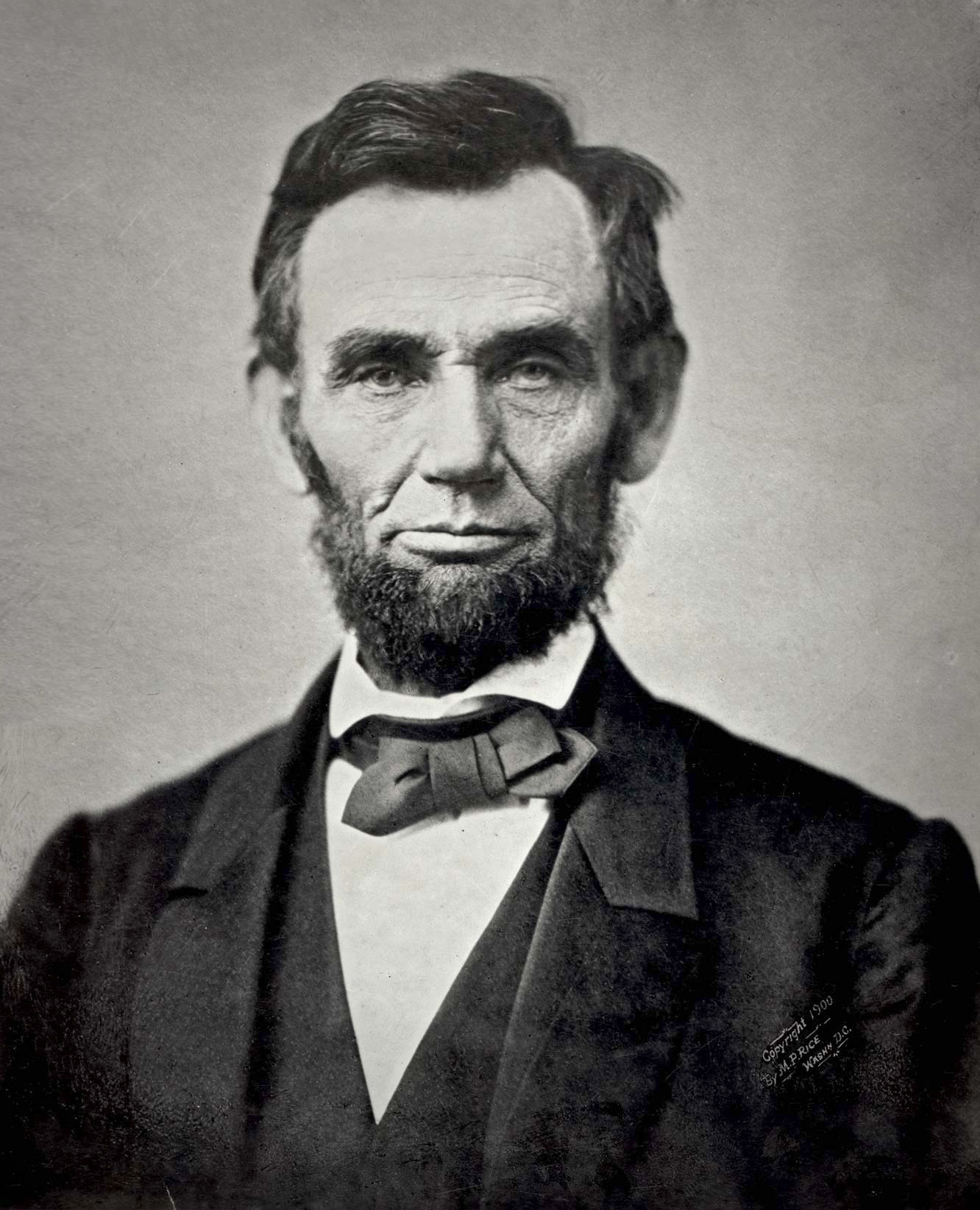

150th Anniversary Commemoration Of The American Civil War –In Honor Of The Abraham

Lincoln-Led Union Side-The Hard Years Of War- A Sketch-Wilhelm Sorge’s War-Take Two

From

The Pen Of Frank Jackman

I would not expect any average

American citizen today to be familiar with the positions of the communist

intellectuals and international working-class party organizers (First

International) Karl Mark and Friedrich Engels on the events of the American

Civil War. There is only so much one can expect of people to know off the top of

their heads about what for several generations now has been ancient

history. I am, however, always amazed

when I run into some younger leftists and socialists, or even older radicals

who may have not read much Marx and Engels, and find that they are surprised,

very surprised to see that Marx and Engels were avid partisans of the Abraham

Lincoln-led Union side in the American Civil War. I, in the past, have placed a

number of the Marx-Engels newspaper articles from the period in this space to

show the avidity of their interest and partisanship in order to refresh some

memories and enlighten others. As is my wont I like to supplement such efforts

with little fictional sketches to illustrate points that I try to make and do

so below with my take on a Union soldier from Boston, a rank and file soldier,Wilhelm

Sorge.

Since Marx and Engels have always

been identified with a strong anti-capitalist bias for the unknowing it may

seem counter-intuitive that the two men would have such a positive position on

events that had as one of its outcomes an expanding unified American capitalist

state. A unified capitalist state which ultimately led the vanguard political

and military actions against the followers of Marx and Engels in the 20th

century in such places as Russia, China, Cuba and Vietnam. The pair were

however driven in their views on revolutionary politics by a theory of

historical materialism which placed support of any particular actions in the

context of whether they drove the class struggle toward human emancipation

forward. So while the task of a unified capitalist state was supportable alone

on historical grounds in the United States of the 1860s (as was their qualified

support for German unification later in the decade) the key to their support

was the overthrow of the more backward slave labor system in one part of the

country (aided by those who thrived on the results of that system like the

Cotton Whigs in the North) in order to allow the new then progressive

capitalist system to thrive.

In the age of advanced imperialist

society today, of which the United States is currently the prime example, and

villain, we find that we are, unlike Marx and Engels, almost always negative

about capitalism’s role in world politics. And we are always harping on the

need to overthrow the system in order to bring forth a new socialist

reconstruction of society. Thus one could be excused for forgetting that at

earlier points in history capitalism played a progressive role. A role that

Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky and other leading Marxists, if not applauded, then

at least understood represented human progress. Of course, one does not expect

everyone to be a historical materialist and therefore know that in the Marxist

scheme of things both the struggle to bring America under a unitary state that

would create a national capitalist market by virtue of a Union victory and the

historically more important struggle to abolish slavery that turned out to be a

necessary outcome of that Union struggle were progressive in the eyes of our

forebears, and our eyes too.

Furthermore few know about the fact

that the small number of Marxist supporters in the United States during that

Civil period, and the greater German immigrant communities here that where

spawned when radicals were force to flee Europe with the failure of the German

revolutions of 1848 were mostly fervent supporters of the Union side in the

conflict. Some of them called the “Red Republicans” and “Red 48ers” formed an

early experienced military cadre in the then fledgling Union armies. Below is a

short sketch drawn on the effect that these hardened foreign –born

abolitionists had on some of the raw recruits who showed up in their regiments

and brigades during those hard four years of fighting, the last year of which

we are commemorating this month.

*************

Wilhelm Sorge, as he looked around the town, as he saw the dirty dusty streets of Boston clogged with rampaging rain-washed mucks and in some physical disrepair, especially the sidewalks weighted down with well-wishers who continued to come out to cheer on the departing boys, in some need of fixing after all the endless regiments raised helped create this condition after almost a year of war. The Brothers’ war they were beginning to call it around the press rooms not so much because of the eleven state departure as because the social tensions around the slavery issue were decimating many families, arms in hand, North and South, creating schisms that would not heal for years, if ever. All this time, all the almost year the war against the departed brethren down south who had gone on to form their own nation had gone, had made Wilhelm pensive.

Boston, although Wilhelm had not been born here but in Cologne over in Germany he, unlike his father who due to his damn “red republican” politics and the fellowship of his youth, including those who perished on the barricades or died rotting in jail would always be a Cologne man at heart but he had come of age here and felt differently, felt that his fate was tied in with America whatever the final outcome of the war. He thought back to how his father, Friedrich, the owner of small print shop on Milk Street, a former barricade fighter in his native Cologne back in ’48 (as his father would say it when discussing that time with his peer fellow exiles at the German-American club over on Hanover Street), a known “high abolitionist” around town had played his part in raising that dust that he saw before him with his endless tirades about the necessity of creating regiments in preparation for the civil war that he knew in his bones was coming, seeming ever since Kansas times back in the mid-50s when Friedrich tirelessly raised money for arms to the Kansas abolitionists in their fight against the pro-slavery elements. Probably raised money among the German exiles for that monomaniac John Brown who started this whole conflagration.

They had, father and son, argued constantly for a time about Wilhelm’s enlisting in the fight, in Massa Lincoln’s fight Wilhelm called it, mocking the speech pattern of the nigras who worked the warehouses at Sanborne and Son. That argument had eventually died down if it had not been extinguished when both men had seen that the other’s arguments held no sway, and perhaps best left unsaid since the daily casualty reports posted in front of the Gazette office and the increasing number of mothers, aunts, sisters, sweethearts dressed in funeral black spoke to the appalling loses. Losses that perhaps only a brothers’ war could unleash. Wilhelm flat out saw no reason to fight, saw benefits to his career as a budding factor such as it was by keeping out of the fight and decidedly did not want to lift a finger to free the sweaty turgid slaves. Wilhelm was by no measure his father’s son on that score.

As Wilhelm thought about the present political situation thinking amid the dust clouds being raised as he walked along Tremont Street he said to himself that no, he had decidedly not changed his mind over that time, over the year since he and his father had first quarreled, and subsequently, every time, every damn time his father, the “high abolitionist” Friedrich Sorge held forth on his favorite subject-freeing the “nigras.” Or rather his favorite subject of having his eldest son, one Wilhelm Sorge, him, put on the blue uniform of the Union side and go down south, south somewhere and fill in a spot in the depleting armies of the North. There were plenty of farm boys and mill hands eager to lay down their heads on some bloody battlefield with a white tombstone for a pillow for that cause.

No, as well, he had not changed his mind one bit about how his employers had been “robbed” since the military actions had started the previous year and the flow of cotton had been so diminished that he was only working his clerk’s job at the Sanborne and Sons warehouses three days a week, and the factor job was being held up indefinitely. The damn Lincoln naval blockade and the wimpy position of the British in their Ponius Pilate washing hands on the matter had wreaked havoc on supplies coming through. He was supplementing that meager wage working for Jim Smith, the former neighborhood blacksmith now turned small arms manufacturer, who was always in need of a smart clerk who also had a strong pair of hands and back to work on the artillery carriages that he produced on order from Massachusetts Legislature for the Army of the Potomac. And, no, one thousand times no he had not changed his mind about the nigra stinks that had bothered him when they had worked at the Sanborne warehouses in the days before secession when those locations were filled with beautiful southern cotton that needed to be hauled on or off waiting ships dockside.

What was making Wilhelm really pensive though, making him think every once in a while a vagrant thought about joining up in the war effort was that all his friends, his old Klimt school friends and Goethe Club friends had enlisted in one of the waves of the various deployments of Massachusetts-raised regiments. Those friends had baited him about his manhood even as he offered to take them on one by one or collectively if they so desired to see who the real man was. Moreover he grew pensive, and somewhat sheepish, every time he passed by the German graveyard on Milk Street where he could see fresh flowers sticking out of urns in front of newly buried soldier boys. Soldier boys like Werther Schmidt, his school friend, whose mother was daily prostrate before his fresh-flowered grave. He would cross the street when he spied her all in black coming up the other way for he could not stand the look she would give him when she passed. Gave him like he, not some Johnny Reb or more likely some disease, had been the cause of poor Werther’s death.

But who was he kidding. Lately Wilhelm Sorge had not become pensive as a result of pressure from his father and friends, nor about his reduced circumstances, nor about Negro stinks but about what Miss Lucinda Mason thought of him. Miss Lucinda Mason whose father, like his, was a “high abolitionist” and was instrumental in assisting in forming the newly authorized regiments in Massachusetts. And while her father was mildly tolerate of Wilhelm’s slackness about serving his country Lucinda, while smitten by her German young man met at a dance to raise funds for the Union efforts of all places, continually harped on the need for him to “enter service” as she called it. And of course if the rosy-cheeked, wasp-waisted Miss Lucinda Mason harped on an issue then that indeed would make a man pensive. Yes, it was like that with young Wilhelm about Miss Lucinda Mason.