Lessons from 20th Century Alabama's Black Communists for Black Lives Matter

On the 25th anniversary of the groundbreaking history, Hammer and Hoe, author Robin D.G. Kelley discusses the lessons Alabama’s forgotten black communists can offer today’s activists.

August 31, 2015

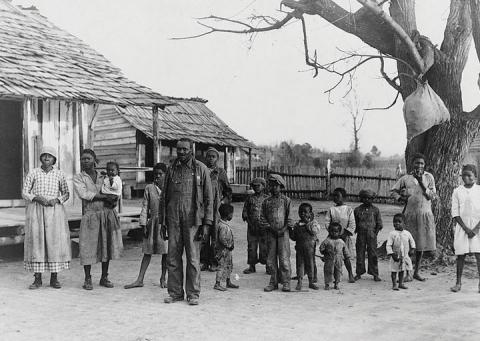

A sharecropping family.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/08/alabama-hammer-and-hoe-robin-kelley-communist-party/

When historian Robin D. G. Kelley began work in the 1980s on what would become his classic work of radical history, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression, he was surrounded by activism. There was an uprising against police violence in Liberty City, Florida; multiracial coalitions propelled Harold Washington to the mayor’s office in Chicago; and the presidential campaign of Jesse Jackson was gathering steam. As a young activist and campus organizer, Kelley was part of the movement that pushed the University of California system to divest from its holdings in South Africa, but he was also discovering a tradition of black radical organizing closer to home—that of the Communist Party in Alabama.

Kelley’s dissertation on that subject became Hammer and Hoe, a book that explores what might have seemed to be a fairly esoteric topic yet offered lessons that activists have been drawing on for twenty-five years. Throughout that time, the book has remained in print, winning awards and, more important to Kelley, a place in the hearts and strategic thinking of decades of young organizers struggling with the questions of race, gender, class, and solidarity.

In Hammer and Hoe, Kelley details in wonderfully vivid prose how black workers in Alabama made communism their own, blending the teachings of Marx and Lenin with those of the black church and the lessons of decades of resistance to slavery, segregation, and racist terrorism. They were sharecroppers and domestic workers, relief recipients and factory workers. They were men and women who had been denied access to “skilled” positions so that white men could take the jobs instead, and, through those experiences, had found their way to a radicalism that was international in scope but deeply local in practice.

Those Alabama communists, Kelley notes, did not see their struggles for voting rights as separate from their struggles against economic exploitation by property owners, factory bosses, or the ostensibly progressive leaders of an unequal New Deal order. To be able to fight either of those struggles they had to challenge the racist terror of the Ku Klux Klan, often in collusion with the police, and to escape the clutches of a criminal legal system that locked up and executed black people based on the thinnest shreds of evidence. The trials of the Scottsboro Nine are in Hammer and Hoe, but so are the stories of many people who have been forgotten, who dared to stand up to injustice and paid with their lives.

This summer, the University of North Carolina press published an updated, 25th-anniversary edition of the book. With a nod to the present moment, this edition comes with a new preface and a dedication to the young activists of recent years, whose fights against austerity, racism, militarism, and capitalism itself have echoed, consciously or unconsciously, the struggles of Kelley’s subjects.

Kelley is currently the Gary B. Nash Professor of American History at UCLA. He sat for an interview with The Nation Sarah Jaffe over this summer. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Sarah Jaffe: You write in the new preface that more people have reached out to you about this book than any other in the past few years. Why do you think that is?

Robin Kelley: The book does a few things that interest readers today. It is about a radical social movement that really was trying to shift the paradigm—it wasn’t about making better reforms, it wasn’t operating within the Democratic Party—in a very unlikely place like Alabama, where the conditions of repression were so enormous. [In doing so], it links two [contemporary] movements that we now think of as separate. One is anti-capitalism and its roots in the Occupy movement and elsewhere, the other is what has now been identified as Black Lives Matter, the struggle against police violence and the carceral state. It just so happens that the Communist party in Alabama focused on these two things directly. And for them these were inseparable.

SJ: You write about the end of the Cold War and how anti-capitalism has begun to rise again since the 2008 financial crisis. Do you think this country is finally ready to understand the contributions of socialists and Communists to its history and to its present?

RK: The Cold War has been so thoroughly suppressed in the public consciousness that there are whole generations of people who don’t have a clue. I have students who don’t even know what the Cold War is.

That kind of erasure creates a blank space. That’s the good news. The bad news is that the frame of reference has become so slim that the key debates even among some of the most vocal advocates for Occupy has been how to reform capitalism, and that really is about returning to the welfare state or imposing regulation, thinking capitalism is going to be with us forever, it’s just the way it is. But unless we can actually break paradigmatically with the structure of capitalism itself we’re not going to come up with good alternatives.

I think Naomi Klein’s book is important because she’s saying that capitalism itself is the problem. The question is, when can activists have the time and luxury to sit down and say, “How do we actually rebuild our new society?”

There’s a sense that we’re in a state of emergency. You’ve got home foreclosures and you’ve got death. You’ve got dispossession. You’ve got people who don’t have access to water. But then, to be honest, all those models of trying to create the alternative to capitalist living in indigenous communities, whether it’s the Zapatistas or elsewhere, have actually come out of states of emergency.

How does Hammer and Hoe relate to that? No one’s going to read that book and say the Communists of Alabama were able to create socialism. But they were functioning in a state of emergency and they were able to surmount differences that today, in today’s identity politics, people think are insurmountable. They got white people from the Klan to join their organization. Not all of them. But if you can get one, I’m applauding you!

The fact that they were able to make those leaps, that’s not tolerance of difference. That’s a transformational identity in a transformational movement that says we’re comrades.

SJ: You write about the way the Alabama communist party grew from the cultures and ideas of the people it served—particularly Alabama’s black working class—and the way that the white left has trouble sometimes seeing and understanding the black left. How are white progressives still misreading the black left?

RK: This is a mantra that has been repeated since the 19th century at least: that issues of race or issues of gender, that those issues are somehow a distraction from the real issues. But history has proven that these things are inseparable, because creating hierarchies of difference is essentially an ideological and economic project.

Slavery and dispossessing Indians and making sure that women are being paid wages that could allow them to buy hats, these are ideologies that actually structure capitalism. Anyone who’s serious about socialism, or some kind of non-capitalist path for development, must address them not as separate issues but as issues that help us have a deeper analysis of how political economy works. Again I come back to Hammer and Hoe, because part of the critique of the New Deal was to say this great welfare state expansion was built on a racial hierarchy in which they were allowed to pay black workers in public works programs less money, or pay southern workers less money than northern. In other words, it’s a hierarchy structured by race, by class, by gender. Unless we understand how the structure works we’ll never be able to address the economic problems.

Is making a revolution simply about having a fairer state? Making sure that everyone has decent housing? Or is it about changing our relationships to one another so that you don’t need state violence to keep the machine operating? How do you actually create a culture in which you can actually have something like a beloved community, where the struggle for the community is part of the project of making change?

That’s part of what I think the best elements of Occupy were trying to do, the best elements of Black Lives Matter: create new community.

SJ: You also wrote about the way white people’s fear of “social equality” for black people was a fear of interracial sex—a fear we heard echoed in Dylann Roof’s statement to his victims as he pulled the trigger in Charleston. Can you talk a bit about that, and the way the Alabama Communists organized against it?

RK: From the very inception of the Communist Party’s presence in the south, anticommunists used sex as a way to mobilize fear and opposition. “What Communists want to do is nationalize your daughters”—I love that line. It’s the combination of sexual depravity associated with Communism and the fact that black rights was a central position. This is one of the ways they were able to keep people away from the Party. It didn’t quite work because, of course, in the south, then and now, there’s never been any real barriers to interracial sex. Especially if you’re talking about white men and women of color. Ask Strom Thurmond about that.

The issue is ultimately about the white supremacy’s treatment of women as property. It’s about women as property, masked in the form of security. For Dylann Roof to make the statement and kill six black women, out of nine, is to also repeat the notion that white women are mere property and that his job is to protect that property from being sullied by black men. That black men are natural rapists is such an old but ingrained myth that I can’t imagine what it’s going to take to uproot it.

SJ: Hammer and Hoe takes place during the Great Depression; we’re still living with the effects of the Great Recession. Can you compare and contrast the organizing that was happening then around jobs and labor and the unemployed, and what’s happening now?

RK: Nothing in the New Deal was a gift, it was all struggled over and fought for. The best parts of the New Deal weren’t so much relief. It was Section 7 of the National Industrial Recovery Act that said workers have the right to organize. Then in 1935 it became stronger. The fact that in most places, industrial trade unions could organize with some limited protections from the state allowed unions to grow.

Strong community-based organizing really matters. Nowadays there’s so much mobility, so much displacement that the notion of an established community, those days are over. So what takes its place? Virtual organizing. And I’m not criticizing it at all because I think it’s played a very important role in being able to mobilize huge numbers of people for different events. The problem is that virtual organizing, while successful at mobilizing for events, it’s very hard to sustain the day-to-day organizational structure that is required for long-term struggles.

People are trying to figure out how we develop stronger organizations—not bigger organizations, because, even in the days of the New Deal, some of the most effective movements were never huge mass movements, but they were movements that were able to sustain themselves, and they were movements that were able to put forward what we think of as transformative demands.

Transformative demands are those demands that, on the one hand, attend to a particular crisis, whether it’s we need relief or we need housing, etc. But then those demands are ratcheted up and ultimately question the very logic of the prevailing system. If you say we need housing then the state could respond and say, “We’re going to have a market system providing housing,” and they’re like, “no, that’s not going to work, we’re going to demand something different than a market-based system.”

One of the problems with so many exciting movements today is this tendency not to make transformative demands, not to make any demands, because somehow making a demand would formalize an organization in such a way where it would undermine democracy, it could be co-opted by the Democratic party or co-opted by the trade unions or whatever. So without those demands you don’t have a space or a platform in which to have a debate over what the future looks like.

I’m not saying it’s fixed like that. There are lots of organizations today that are making transformative demands, I name some in the book. But whatever we think about the problems of the Communist Party, and there are many, it was an international organization that was well-organized and put forward transformative demands.

I don’t know whether the refusal to make demands can lead to something even better. But one of the consequences is that you end up having a segment of the movement embrace the Obama administration’s agenda, which is that racial profiling is bad policing so we need more effective policing, body cameras for cops, better officer training, this sort of thing. We know from the history that none of that stuff really makes a difference. What we’re looking for is transformative changes, eventually the elimination of state violence and the police force itself.

SJ: In Hammer and Hoe, there’s a lot about the way violence was used specifically to quell labor and left organizing by black people in Alabama. You write, “Most scholars have underestimated the Southern Left and have underrated the role violence played in quashing radical movements…”

RK: State violence was necessary to suppress labor-based movements, any social justice movements. It was necessary to intimidate whole groups of people from even thinking about coming together. It was so embedded in the structure of everyday life that it became second nature. There was a constant distrust of working people who spoke up. A constant distrust of black people. And a capacity to transfer that distrust to white working people who gave up cooperation for the sake of security.

The security of whiteness is a very fragile security. You have these systems operating, and at the base of them all is violence. Violence also becomes endemic in the culture in which men and women and children and parents inside their own households embrace that violence as a way to maintain hierarchy within those structures. They mirror the violence of the state. Private violence is tied directly to public violence.

Violence is everywhere, so unless we see that and understand its relationship to the maintenance of the current political economy we’re going to treat public violence separate from private violence, gendered private violence as a separate thing. You’ve got police violence, which is very much tied to economic justice issues, because where does that police violence take place for the most part? In places like Baltimore where you can have a black regime running a city but people whose lives depend on the good graces of their neighbors, on very low wages, whatever’s left of the welfare state. People who live precarious lives are the ones who are most likely to experience that state violence.

That’s why whenever we have exceptional cases, people who actually are not living precarious lives, they just happen to be black, those are the stories that are raised up. They are important, but to raise them up above all other stories of state violence is to basically produce an analysis that’s devoid of class and that separates out the political economy from state violence.

We have to go back and make sure that we understand the relationship between all these forms of violence and their relationship to the economy, and not think of the economy as simply wages, housing, working conditions, consumerism, trade—economy is so much more than that. Economy is access to resources. Economy is being able to live a life that’s not precarious. Economy is racial. Economy is gendered. Economy is not a separate category from race or gender.

SJ: You write about how law enforcement and the state were complicit in extralegal violence and lynching, how law enforcement would arrest some organizer and turn him over to the Klan. How should that inform our understanding of situations like the killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman?

RK: One of the ways, at least in the 1930s and before that, that the state was able to avoid the expense of prosecution, the expense of detention and also allow for the reproduction of white supremacy on a mass basis was lynching. You think of lynching as terrorizing black communities, terrorizing Mexican communities, it definitely does that. But what it also does is consolidate a white working class investment in a notion of security in a juridical structure that allows them some semblance of citizenship. These are people who, when you really look at their daily life, barely have the privileges of citizenship except in lynching. They could participate even if it’s just as observer.

Naomi Murakawa has this really important book called The First Civil Right, and she shows we had some changes: The Truman administration pushed forward civil rights legislation, more resources for policing to try to stop these kinds of acts of violence. Those resources then fed into a growing criminal justice system. What we end up getting is fewer lynchings—police shooting someone in the back isn’t exactly a lynching, it doesn’t function in the same way. Is it murder? Absolutely. Is it extrajudicial? Yes.

So the reduction of lynchings also means the expansion of a criminal justice system, which actually does detain live bodies and contain them and corrals them. It burgeons and burgeons. It also means that these extrajudicial killings take place with the sanction of the state. Now it’s with police officers who are better armed than they ever were. What hasn’t changed is the basic racial structure of the criminal justice process. The mechanisms change, the processes change, and those processes have enormous consequences, but the basic ideology over time, it’s tweaked.

SJ: Related to both of those, what about the use of armed self-defense among the people you researched? What can we learn from them to apply to today’s conversations about “riots” and how we’re obsessed with particularly black resistance being nonviolent?

RK: One of the biggest myths that is still perpetuated today is that somehow the only natural and legitimate forms of black politics have to embrace nonviolence. No other political agenda or movement has to do the same.

Nonviolence as a political strategy was pretty common among progressive forces in the postwar period, for good reason. However, if you take the history of black freedom struggles, self-defense has been the first principle. It had to be—during Reconstruction something like 58,000 black people were killed. Akinyele Omowale Umoja has this great book called We Will Shoot Back where he proves that in every county in Mississippi where you had organized armed self-defense they had less violence, fewer killings.

Now there’s a difference between armed self-defense and violence as a strategy of resistance. Riots are not necessarily violent strategies of resistance. Riots are oftentimes attacks on property. If you look at the body count of who dies in riots, it’s mostly the people who live in the ghettos. If we look at the body count of the history of riots, even going back to the late 19th and early 20th century, Tulsa, these are racial pogroms where, again, it’s mobs of white people reinforcing their citizenship and white privilege through the violence against the black bodies. Black people have been more the victims of violence than perpetrators of violence against the state.

These are the kind of mythologies that we have to contend with. The amazing thing about the Communist Party in Alabama is that they had dramatic moments and shootouts, yes, in the rural areas in particular you had these moments of militancy, but most of the activists, their strategy was more tricksterism, they wanted to avoid violence to live another day. They knew that they were outnumbered and they were outgunned and so they had to find strategies that were not nonviolent or proviolent but ones that were self-preserving and sustainable.

That’s why every time the question is raised or people have to pronounce their nonviolent intent, that’s about projecting the violence of the state onto the bodies of the very people who are the victims of violence. I am a supporter of nonviolence, but that’s another story.

SJ: Why do you think all of this is happening now?

RK: I think that these movements had been bubbling under the surface, especially with the Clinton administration. Clinton was such a disappointment that a lot of the oppositional movements that have laid the foundation for Occupy were established in the ’90s under Clinton, against welfare deform and all that. To me, the level of organization in preparation for Occupy means that Occupy wasn’t spontaneous. It was an opportunity. The crisis of 2008 was an opportunity, the mobilization around Trayvon Martin and the wave of deaths and social media create opportunities for existing organizations to become visible. If we did not have organization, we wouldn’t have this, that’s my argument. It goes against some of the prevailing wisdom, which is that the conditions just made people so angry and so frustrated that they came out. There’s some of that, but you can’t get people out without organization. That’s why, if there’s a lesson in here, it’s that you’ve got to always organize—whether it’s the optimal time or the non-optimal time, you’ve got to be ready, always.

Kelley’s dissertation on that subject became Hammer and Hoe, a book that explores what might have seemed to be a fairly esoteric topic yet offered lessons that activists have been drawing on for twenty-five years. Throughout that time, the book has remained in print, winning awards and, more important to Kelley, a place in the hearts and strategic thinking of decades of young organizers struggling with the questions of race, gender, class, and solidarity.

In Hammer and Hoe, Kelley details in wonderfully vivid prose how black workers in Alabama made communism their own, blending the teachings of Marx and Lenin with those of the black church and the lessons of decades of resistance to slavery, segregation, and racist terrorism. They were sharecroppers and domestic workers, relief recipients and factory workers. They were men and women who had been denied access to “skilled” positions so that white men could take the jobs instead, and, through those experiences, had found their way to a radicalism that was international in scope but deeply local in practice.

Those Alabama communists, Kelley notes, did not see their struggles for voting rights as separate from their struggles against economic exploitation by property owners, factory bosses, or the ostensibly progressive leaders of an unequal New Deal order. To be able to fight either of those struggles they had to challenge the racist terror of the Ku Klux Klan, often in collusion with the police, and to escape the clutches of a criminal legal system that locked up and executed black people based on the thinnest shreds of evidence. The trials of the Scottsboro Nine are in Hammer and Hoe, but so are the stories of many people who have been forgotten, who dared to stand up to injustice and paid with their lives.

This summer, the University of North Carolina press published an updated, 25th-anniversary edition of the book. With a nod to the present moment, this edition comes with a new preface and a dedication to the young activists of recent years, whose fights against austerity, racism, militarism, and capitalism itself have echoed, consciously or unconsciously, the struggles of Kelley’s subjects.

Kelley is currently the Gary B. Nash Professor of American History at UCLA. He sat for an interview with The Nation Sarah Jaffe over this summer. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Sarah Jaffe: You write in the new preface that more people have reached out to you about this book than any other in the past few years. Why do you think that is?

Robin Kelley: The book does a few things that interest readers today. It is about a radical social movement that really was trying to shift the paradigm—it wasn’t about making better reforms, it wasn’t operating within the Democratic Party—in a very unlikely place like Alabama, where the conditions of repression were so enormous. [In doing so], it links two [contemporary] movements that we now think of as separate. One is anti-capitalism and its roots in the Occupy movement and elsewhere, the other is what has now been identified as Black Lives Matter, the struggle against police violence and the carceral state. It just so happens that the Communist party in Alabama focused on these two things directly. And for them these were inseparable.

SJ: You write about the end of the Cold War and how anti-capitalism has begun to rise again since the 2008 financial crisis. Do you think this country is finally ready to understand the contributions of socialists and Communists to its history and to its present?

RK: The Cold War has been so thoroughly suppressed in the public consciousness that there are whole generations of people who don’t have a clue. I have students who don’t even know what the Cold War is.

That kind of erasure creates a blank space. That’s the good news. The bad news is that the frame of reference has become so slim that the key debates even among some of the most vocal advocates for Occupy has been how to reform capitalism, and that really is about returning to the welfare state or imposing regulation, thinking capitalism is going to be with us forever, it’s just the way it is. But unless we can actually break paradigmatically with the structure of capitalism itself we’re not going to come up with good alternatives.

I think Naomi Klein’s book is important because she’s saying that capitalism itself is the problem. The question is, when can activists have the time and luxury to sit down and say, “How do we actually rebuild our new society?”

There’s a sense that we’re in a state of emergency. You’ve got home foreclosures and you’ve got death. You’ve got dispossession. You’ve got people who don’t have access to water. But then, to be honest, all those models of trying to create the alternative to capitalist living in indigenous communities, whether it’s the Zapatistas or elsewhere, have actually come out of states of emergency.

How does Hammer and Hoe relate to that? No one’s going to read that book and say the Communists of Alabama were able to create socialism. But they were functioning in a state of emergency and they were able to surmount differences that today, in today’s identity politics, people think are insurmountable. They got white people from the Klan to join their organization. Not all of them. But if you can get one, I’m applauding you!

The fact that they were able to make those leaps, that’s not tolerance of difference. That’s a transformational identity in a transformational movement that says we’re comrades.

SJ: You write about the way the Alabama communist party grew from the cultures and ideas of the people it served—particularly Alabama’s black working class—and the way that the white left has trouble sometimes seeing and understanding the black left. How are white progressives still misreading the black left?

RK: This is a mantra that has been repeated since the 19th century at least: that issues of race or issues of gender, that those issues are somehow a distraction from the real issues. But history has proven that these things are inseparable, because creating hierarchies of difference is essentially an ideological and economic project.

Slavery and dispossessing Indians and making sure that women are being paid wages that could allow them to buy hats, these are ideologies that actually structure capitalism. Anyone who’s serious about socialism, or some kind of non-capitalist path for development, must address them not as separate issues but as issues that help us have a deeper analysis of how political economy works. Again I come back to Hammer and Hoe, because part of the critique of the New Deal was to say this great welfare state expansion was built on a racial hierarchy in which they were allowed to pay black workers in public works programs less money, or pay southern workers less money than northern. In other words, it’s a hierarchy structured by race, by class, by gender. Unless we understand how the structure works we’ll never be able to address the economic problems.

Is making a revolution simply about having a fairer state? Making sure that everyone has decent housing? Or is it about changing our relationships to one another so that you don’t need state violence to keep the machine operating? How do you actually create a culture in which you can actually have something like a beloved community, where the struggle for the community is part of the project of making change?

That’s part of what I think the best elements of Occupy were trying to do, the best elements of Black Lives Matter: create new community.

SJ: You also wrote about the way white people’s fear of “social equality” for black people was a fear of interracial sex—a fear we heard echoed in Dylann Roof’s statement to his victims as he pulled the trigger in Charleston. Can you talk a bit about that, and the way the Alabama Communists organized against it?

RK: From the very inception of the Communist Party’s presence in the south, anticommunists used sex as a way to mobilize fear and opposition. “What Communists want to do is nationalize your daughters”—I love that line. It’s the combination of sexual depravity associated with Communism and the fact that black rights was a central position. This is one of the ways they were able to keep people away from the Party. It didn’t quite work because, of course, in the south, then and now, there’s never been any real barriers to interracial sex. Especially if you’re talking about white men and women of color. Ask Strom Thurmond about that.

The issue is ultimately about the white supremacy’s treatment of women as property. It’s about women as property, masked in the form of security. For Dylann Roof to make the statement and kill six black women, out of nine, is to also repeat the notion that white women are mere property and that his job is to protect that property from being sullied by black men. That black men are natural rapists is such an old but ingrained myth that I can’t imagine what it’s going to take to uproot it.

SJ: Hammer and Hoe takes place during the Great Depression; we’re still living with the effects of the Great Recession. Can you compare and contrast the organizing that was happening then around jobs and labor and the unemployed, and what’s happening now?

RK: Nothing in the New Deal was a gift, it was all struggled over and fought for. The best parts of the New Deal weren’t so much relief. It was Section 7 of the National Industrial Recovery Act that said workers have the right to organize. Then in 1935 it became stronger. The fact that in most places, industrial trade unions could organize with some limited protections from the state allowed unions to grow.

Strong community-based organizing really matters. Nowadays there’s so much mobility, so much displacement that the notion of an established community, those days are over. So what takes its place? Virtual organizing. And I’m not criticizing it at all because I think it’s played a very important role in being able to mobilize huge numbers of people for different events. The problem is that virtual organizing, while successful at mobilizing for events, it’s very hard to sustain the day-to-day organizational structure that is required for long-term struggles.

People are trying to figure out how we develop stronger organizations—not bigger organizations, because, even in the days of the New Deal, some of the most effective movements were never huge mass movements, but they were movements that were able to sustain themselves, and they were movements that were able to put forward what we think of as transformative demands.

Transformative demands are those demands that, on the one hand, attend to a particular crisis, whether it’s we need relief or we need housing, etc. But then those demands are ratcheted up and ultimately question the very logic of the prevailing system. If you say we need housing then the state could respond and say, “We’re going to have a market system providing housing,” and they’re like, “no, that’s not going to work, we’re going to demand something different than a market-based system.”

One of the problems with so many exciting movements today is this tendency not to make transformative demands, not to make any demands, because somehow making a demand would formalize an organization in such a way where it would undermine democracy, it could be co-opted by the Democratic party or co-opted by the trade unions or whatever. So without those demands you don’t have a space or a platform in which to have a debate over what the future looks like.

I’m not saying it’s fixed like that. There are lots of organizations today that are making transformative demands, I name some in the book. But whatever we think about the problems of the Communist Party, and there are many, it was an international organization that was well-organized and put forward transformative demands.

I don’t know whether the refusal to make demands can lead to something even better. But one of the consequences is that you end up having a segment of the movement embrace the Obama administration’s agenda, which is that racial profiling is bad policing so we need more effective policing, body cameras for cops, better officer training, this sort of thing. We know from the history that none of that stuff really makes a difference. What we’re looking for is transformative changes, eventually the elimination of state violence and the police force itself.

SJ: In Hammer and Hoe, there’s a lot about the way violence was used specifically to quell labor and left organizing by black people in Alabama. You write, “Most scholars have underestimated the Southern Left and have underrated the role violence played in quashing radical movements…”

RK: State violence was necessary to suppress labor-based movements, any social justice movements. It was necessary to intimidate whole groups of people from even thinking about coming together. It was so embedded in the structure of everyday life that it became second nature. There was a constant distrust of working people who spoke up. A constant distrust of black people. And a capacity to transfer that distrust to white working people who gave up cooperation for the sake of security.

The security of whiteness is a very fragile security. You have these systems operating, and at the base of them all is violence. Violence also becomes endemic in the culture in which men and women and children and parents inside their own households embrace that violence as a way to maintain hierarchy within those structures. They mirror the violence of the state. Private violence is tied directly to public violence.

Violence is everywhere, so unless we see that and understand its relationship to the maintenance of the current political economy we’re going to treat public violence separate from private violence, gendered private violence as a separate thing. You’ve got police violence, which is very much tied to economic justice issues, because where does that police violence take place for the most part? In places like Baltimore where you can have a black regime running a city but people whose lives depend on the good graces of their neighbors, on very low wages, whatever’s left of the welfare state. People who live precarious lives are the ones who are most likely to experience that state violence.

That’s why whenever we have exceptional cases, people who actually are not living precarious lives, they just happen to be black, those are the stories that are raised up. They are important, but to raise them up above all other stories of state violence is to basically produce an analysis that’s devoid of class and that separates out the political economy from state violence.

We have to go back and make sure that we understand the relationship between all these forms of violence and their relationship to the economy, and not think of the economy as simply wages, housing, working conditions, consumerism, trade—economy is so much more than that. Economy is access to resources. Economy is being able to live a life that’s not precarious. Economy is racial. Economy is gendered. Economy is not a separate category from race or gender.

SJ: You write about how law enforcement and the state were complicit in extralegal violence and lynching, how law enforcement would arrest some organizer and turn him over to the Klan. How should that inform our understanding of situations like the killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman?

RK: One of the ways, at least in the 1930s and before that, that the state was able to avoid the expense of prosecution, the expense of detention and also allow for the reproduction of white supremacy on a mass basis was lynching. You think of lynching as terrorizing black communities, terrorizing Mexican communities, it definitely does that. But what it also does is consolidate a white working class investment in a notion of security in a juridical structure that allows them some semblance of citizenship. These are people who, when you really look at their daily life, barely have the privileges of citizenship except in lynching. They could participate even if it’s just as observer.

Naomi Murakawa has this really important book called The First Civil Right, and she shows we had some changes: The Truman administration pushed forward civil rights legislation, more resources for policing to try to stop these kinds of acts of violence. Those resources then fed into a growing criminal justice system. What we end up getting is fewer lynchings—police shooting someone in the back isn’t exactly a lynching, it doesn’t function in the same way. Is it murder? Absolutely. Is it extrajudicial? Yes.

So the reduction of lynchings also means the expansion of a criminal justice system, which actually does detain live bodies and contain them and corrals them. It burgeons and burgeons. It also means that these extrajudicial killings take place with the sanction of the state. Now it’s with police officers who are better armed than they ever were. What hasn’t changed is the basic racial structure of the criminal justice process. The mechanisms change, the processes change, and those processes have enormous consequences, but the basic ideology over time, it’s tweaked.

SJ: Related to both of those, what about the use of armed self-defense among the people you researched? What can we learn from them to apply to today’s conversations about “riots” and how we’re obsessed with particularly black resistance being nonviolent?

RK: One of the biggest myths that is still perpetuated today is that somehow the only natural and legitimate forms of black politics have to embrace nonviolence. No other political agenda or movement has to do the same.

Nonviolence as a political strategy was pretty common among progressive forces in the postwar period, for good reason. However, if you take the history of black freedom struggles, self-defense has been the first principle. It had to be—during Reconstruction something like 58,000 black people were killed. Akinyele Omowale Umoja has this great book called We Will Shoot Back where he proves that in every county in Mississippi where you had organized armed self-defense they had less violence, fewer killings.

Now there’s a difference between armed self-defense and violence as a strategy of resistance. Riots are not necessarily violent strategies of resistance. Riots are oftentimes attacks on property. If you look at the body count of who dies in riots, it’s mostly the people who live in the ghettos. If we look at the body count of the history of riots, even going back to the late 19th and early 20th century, Tulsa, these are racial pogroms where, again, it’s mobs of white people reinforcing their citizenship and white privilege through the violence against the black bodies. Black people have been more the victims of violence than perpetrators of violence against the state.

These are the kind of mythologies that we have to contend with. The amazing thing about the Communist Party in Alabama is that they had dramatic moments and shootouts, yes, in the rural areas in particular you had these moments of militancy, but most of the activists, their strategy was more tricksterism, they wanted to avoid violence to live another day. They knew that they were outnumbered and they were outgunned and so they had to find strategies that were not nonviolent or proviolent but ones that were self-preserving and sustainable.

That’s why every time the question is raised or people have to pronounce their nonviolent intent, that’s about projecting the violence of the state onto the bodies of the very people who are the victims of violence. I am a supporter of nonviolence, but that’s another story.

SJ: Why do you think all of this is happening now?

RK: I think that these movements had been bubbling under the surface, especially with the Clinton administration. Clinton was such a disappointment that a lot of the oppositional movements that have laid the foundation for Occupy were established in the ’90s under Clinton, against welfare deform and all that. To me, the level of organization in preparation for Occupy means that Occupy wasn’t spontaneous. It was an opportunity. The crisis of 2008 was an opportunity, the mobilization around Trayvon Martin and the wave of deaths and social media create opportunities for existing organizations to become visible. If we did not have organization, we wouldn’t have this, that’s my argument. It goes against some of the prevailing wisdom, which is that the conditions just made people so angry and so frustrated that they came out. There’s some of that, but you can’t get people out without organization. That’s why, if there’s a lesson in here, it’s that you’ve got to always organize—whether it’s the optimal time or the non-optimal time, you’ve got to be ready, always.

.jpg)

means if the Senate will not be able to block

the deal

means if the Senate will not be able to block

the deal