Honor An Historic Leader Of The American Abolitionist Movement-John Brown Late Of Harper's Ferry

Chapter Five

Bleeding Kansas

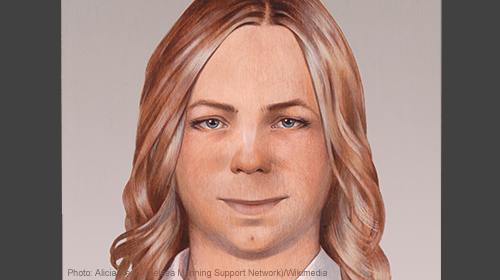

depicting the dominating figure of John Brown against a territorial Kansas background.

| "I found my father and one brother, William, lying dead in the road, . . .; I saw my other brother lying dead on the ground, . . .; his fingers were cut off, and his arms were cut off; his head was cut open; there was a hole in his breast. William’s head was cut open, and a hole was in his jaw, as though it was made by a knife, and a hole was also in his side. My father was shot in the forehead and stabbed in the breast.” – John Doyle affidavit, 1856, Special Congressional Investigative Committee |  | In the aftermath, John Brown decided a blow against the pro-slavery side was needed. On May 23, Brown; his sons Owen, Frederick, Salmon, and Oliver; Henry Thompson and two other men departed for Pottawatomie. Dragging several pro-slavery settlers from their cabins, Brown’s group brutally killed Allen Wilkinson, William Sherman, and James, Drury, and William Doyle and mutilated their bodies. John Brown committed none of the murders himself, which apparently were carried out by Henry Thompson, Theodore Weiner, Owen Brown, and possibly Salmon Brown. However, the elder Brown oversaw their acts and acknowledged afterwards, “I approved of it.” After they were through, the group rejoined the Pottawatomie Rifles. |

| Meanwhile, John Brown and his men joined Captain Samuel Shore and his volunteers on June 1 to march on Black Jack Springs, where a large group of Missouri militia was camped. The next day, this force engaged the Missourians, under the command of Henry Clay Pate. After several hours, Pate and his men surrendered. Brown intended to exchange his prisoners for the release of free-state prisoners, including his two sons. Three days after his victory, however, the Missourians were freed and Brown’s group was broken up by U.S. troops under Col. Edwin Sumner, under orders “to disperse all armed bodies assembled without authority.” |  during the Civil War |

| Kansas was the scene of much violence over the next few months, with both pro-slavery and free-state groups guilty of numerous instances of robbery and murder. During much of the summer, John Brown apparently was inactive, instead tending the ailing Henry Thompson and Salmon Brown, wounded during or after Black Jack, and Owen Brown, sick with fever. In early August, Brown took several members of his family to Nebraska, where he left them, and returned to Kansas with son Frederick. Shortly thereafter, John Brown prepared a “Covenant,” an agreement of the men serving under him to serve as a volunteer force of Kansas Regulars “for the maintainance [sic] of the rights & liberties of the Free-State Citizens of Kansas.” By the end of August, John Brown was encamped near Osawatomie, where an attack by a large pro-slavery force was expected. On August 30, Frederick Brown was shot and killed on the road near Samuel Adair’s cabin by Martin White, who was traveling with the Missourians. Alarm spread through Osawatomie as the pro-slavery group under Gen. John W. Reid approached the town. The much smaller contingent of free-state men was able to delay Reid’s taking of the town for a short period before Reid’s men overwhelmed Brown and his men, took possession of Osawatomie, and burned the town. Accounts from both sides exaggerated the number of casualties from the Battle of Osawatomie. Five free-state men are known to have been killed, while an indeterminant number of pro-slavery men died, possibly in the range of ten. |  dedicated in 1877 to John Brown and the men killed during the Battle of Osawatomie. |

during the Civil War | The arrival of a new governor, John W. Geary, in early September instituted a relatively more peaceful situation in Kansas. John Brown Jr. was released after three months of captivity, but the cabins that he and his brother Jason had built had been destroyed in the aftermath of the Pottawatomie Massacre. John Brown with sons John Jr. and Jason and their families, and son Owen, who had returned to Kansas, headed north out of the territory in October. By December 1856, John Brown was in Ohio visiting relatives. |

Primary Documents:

Letter, Wealthy Brown to Louisa C. Barber, March 23, 1856

Letter, John Brown Jr. to Friend Louisa, March 29, 1856

Letter, John Brown Jr. to Frederick Douglass' Paper, April 4, 1856

Affidavits of Mahala and John Doyle, James Harris, and Louisa Jane Wilkinson on the Pottawatomie Massacre, June 1856

"The Voice of Kansas-Let the South Respond,"De Bow's Review, August 1856

"Articles of Enlistment and By Laws of the Kansas Regulars," 1856 (from Sanborn)

Letter, John Brown to Mary Ann Brown, October 11, 1856

Pamphlet, John Brown, as viewed by H. Clay Pate, 1859

Clipping, Jason Brown to the Akron Beacon, January 21, 1880 (on Pottawatomie Massacre)

Clipping, John Brown Jr. to the Cleveland Leader, November 16, 1883 (on Pottawatomie Massacre)

Clipping, August Bondi to the Kansas Free Press, December 1883

Clipping, August Bondi to the Salina Herald, January 24, 1884

Manuscript, Owen Brown on leaving Kansas in 1856, April 26, 1888

Clipping, Owen Brown on the Fight at Black Jack, Springfield Republican, January 14, 1889

Letter, Salmon Brown to William Connelley, May 28, 1913 (on Pottawatomie Massacre)

Letter, John Brown Jr. to Friend Louisa, March 29, 1856

Letter, John Brown Jr. to Frederick Douglass' Paper, April 4, 1856

Affidavits of Mahala and John Doyle, James Harris, and Louisa Jane Wilkinson on the Pottawatomie Massacre, June 1856

"The Voice of Kansas-Let the South Respond,"De Bow's Review, August 1856

"Articles of Enlistment and By Laws of the Kansas Regulars," 1856 (from Sanborn)

Letter, John Brown to Mary Ann Brown, October 11, 1856

Pamphlet, John Brown, as viewed by H. Clay Pate, 1859

Clipping, Jason Brown to the Akron Beacon, January 21, 1880 (on Pottawatomie Massacre)

Clipping, John Brown Jr. to the Cleveland Leader, November 16, 1883 (on Pottawatomie Massacre)

Clipping, August Bondi to the Kansas Free Press, December 1883

Clipping, August Bondi to the Salina Herald, January 24, 1884

Manuscript, Owen Brown on leaving Kansas in 1856, April 26, 1888

Clipping, Owen Brown on the Fight at Black Jack, Springfield Republican, January 14, 1889

Letter, Salmon Brown to William Connelley, May 28, 1913 (on Pottawatomie Massacre)