From The Anti-War Archives Vietnam and the Soldiers’ Revolt

Volume 68, Issue 02 (June 2016)

Vietnam and the Soldiers’ Revolt

The Politics of a Forgotten History

Derek Seidman is an assistant professor of history at D’Youville College in Buffalo. He is writing a book about the history of GI protest during the Vietnam War.

This article is part of an MR series on the 50th anniversary of the U.S. war in Vietnam.

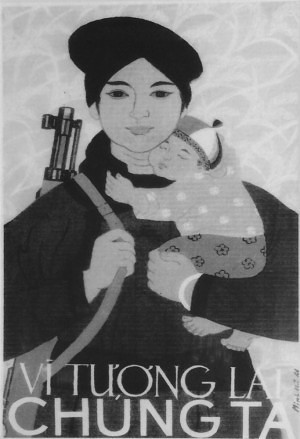

It has been nearly fifty years since the height of the Vietnam War—or, as it is known in Vietnam, the American War—and yet its memory continues to loom large over U.S. politics, culture, and foreign policy. The battle to define the war’s lessons and legacies has been a proxy for larger clashes over domestic politics, national identity, and U.S. global power. One of its most debated areas has been the mass antiwar movement that achieved its greatest heights in the United States but also operated globally. Within this, and for the antiwar left especially, a major point of interest has been the history of soldier protest during the war. This interest grew with the 2003 invasion of Iraq, when both dissident soldiers and antiwar civilians looked back to the legacy of Vietnam-era GI resistance as a usable history to help oppose the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. David Cortright’s classic 1975 account of troop resistance, Soldiers in Revolt, was republished in 2005, and that same year, the documentary film Sir! No Sir! helped to popularize the hidden history of active-duty soldier protest.

Activists looked back to this history for good reason. It was an exciting front within the broader antiwar movement, one that bucked conventional wisdom. Soldiers, such potent symbols of U.S. patriotism, turned their guns around—metaphorically, but also, at times, literally—during a time of war. Thousands of troops protested, petitioned, dissented, disobeyed, and deserted. Antiwar soldiers were strategically important, bestowing a special kind of legitimacy and authority on the peace movement. There was also a more concrete dream: that antiwar GIs, stationed literally at the war’s point of production, had a unique capacity to end it.

Fascinating in itself, the story of Vietnam-era GI protest also serves as a weapon in the ongoing battle over the memory of the Vietnam War. If war is politics by other means, the same could be said about memory and narrative of historical events. The battle to shape our accepted understanding of the past—the stories we recall, the icons and symbols we think of—is deeply linked to political interests.

All sides have attempted to define the collective memory of the Vietnam War in ways that advance their current visions for global and domestic politics and superimpose them on the past. Think, for example, of the persistence of the “spit upon” or “baby killer” myths, or the claim that the antiwar movement “stabbed” soldiers “in the back” (even many of my students, born decades later, say these are the first things they think about when they hear “Vietnam War”).1 The continued influence of these myths has helped prop up consent for militarism at home and abroad. The story of GI protest during the war is an important counter to the conventional story, for it hits at the heart of some of the most emotive symbols in these political battles: the soldiers. It offers grounding for an alternative politics from the antiwar left. It is history worth knowing.

Context

Three larger factors combined to create the context for the rise of Vietnam-era GI protest. The first was the nature of the Vietnam War itself. It was widely unpopular within U.S. society, and this sentiment stretched into the military’s ranks and intensified as the war went on. In Vietnam, the war was deeply disorienting: troops faced harsh natural elements and guerrilla-style tactics, and they often could not distinguish between civilians and soldiers. Few knew why they were fighting; once they arrived in-country, the Cold War rationale for the war felt like a vapid abstraction. The “body count” strategy seemed perverse, and military victories brought no political headway. As the war went on, few wanted to be, as the saying went, the last soldier to die for a mistake. This attitude reverberated beyond combat roles and throughout the whole military.

Second was the conflict between the institutional culture of the Cold War military and lower-ranking soldiers. The military’s conservative, traditionalist norms clashed with the sensibilities of many GIs of the era. Despite formal desegregation, racism was prevalent, with a white-dominated officer corps and pervasive prejudice against blacks. The system of military justice restricted troops’ civil liberties and placed arbitrary power in the hands of higher-ups. In Vietnam, many soldiers felt they were used as pawns by commanders who sent them into dangerous battles to advance their own careers. And with all this, the military was fed by the draft, which coerced two-thirds of all combat troops, mostly poor and working-class youth, into battle.2

Third was the mass appeal of protest politics during the late 1960s and early 1970s. These were years of global insurgency, when millions embraced the spirit of rebellion. The polarization around the war deepened and sank into the consciousness of many troops heading to Vietnam. As two journalists put it, the late-Vietnam era soldier had “seen antiwar sentiment grow into a unifying force for his generation” and come to identify with it instead of the “dispirited remnant of America’s Southeast Asia fighting machine.”3 Three movements were particularly important in shaping GI protest: the antiwar movement, Black Power, and the counterculture. These galvanized many soldiers, offering radical critiques and a language of protest that they brought into the ranks.

Beginnings

The first acts of active-duty GI protest broke out in 1965 and 1966. They were isolated and individualistic, reflecting the infant stage of the broader antiwar movement, as well as the early years of U.S. escalation in Vietnam. But they pioneered a set of aims and tactics that would shape the larger wave of protest to come. Equally important, they emboldened other soldiers and compelled the civilian antiwar left to provide solidarity and material support that would enable the rise of a full-fledged GI movement.

In November 1965, Lieutenant Henry Howe, who was stationed at Fort Bliss, was arrested after attending an antiwar demonstration in El Paso, Texas. Howe was in civilian dress and carried a sign calling President Lyndon Johnson a fascist. The antiwar movement soon organized the “Freedom Now for Lieutenant Howe Committee,” and the ACLU came to his aid. Convicted and jailed for “conduct unbecoming an officer” and “contemptuous words against the President,” Howe became the antiwar movement’s first GI cause célèbre. Others soon followed, including Captain Howard Levy, a dermatologist who refused to train Green Berets headed for Vietnam, and the Fort Hood 3, a trio of young privates who refused shipment to Vietnam. The Fort Hood 3 made the biggest splash yet, sparking New York City’s antiwar left into a defense campaign that signaled the beginning of a civilian-GI alliance. One of the three was in the orbit of the Communist Party, previewing a trend of left involvement in soldier organizing.

By the end of 1966, cases like these had developed an initial set of protest tactics and an agenda for GI dissent that pivoted around civil liberties, racism, and, above all, the war. Others soon built upon these. In 1966 and 1967, Private Andy Stapp organized a group at Fort Sill, Kansas, that became the American Servicemen’s Union (ASU). The ASU framed GIs as the military’s working class and aimed to unionize them along radical, anti-imperialist lines. The group’s eight-point program included demands for “An End to the Saluting and Sir-ing of Officers” and “Rank-and-File Control over Court-Martial Boards.” The ASU was the first organized expression of a lower-ranking GI class politics, and they even garnered a cover story in Esquire.4 Around the same time, the Black Power movement emerged within the ranks. In July 1967, William Harvey and George Daniels, two black marines from Brooklyn, organized a rap session with fellow troops, where they declared that black men had no place fighting a “white man’s war” in Vietnam. The soldiers were court-martialed for “promoting disloyalty” and dealt long prison terms. The prosecutor claimed that Harvey and Daniels created “an extraordinarily dangerous situation” by urging black marines to “stick together” in refusing to go to Vietnam.5 The ASU and Harvey and Daniels drew support from the antiwar movement and politicized other troops. Taken together, these cases of dissent from 1965 to 1967 prepared the way for the larger GI movement.

Up to this time, antiwar activists mostly considered GIs moral symbols whose presence in the movement could help disarm opponents. Yet they also genuinely sympathized with soldiers, viewing them as working-class victims of an unjust war. Throughout its early years, the antiwar movement sought out veterans to speak at rallies and promoted slogans like “Support the G.I.s: Bring Them Home Now!” But the bulk of the civilian movement did not initially see soldiers as a group to be organized. “The idea of looking to GIs as part of the antiwar constituency was considered bizarre at that time by most of the movement,” wrote antiwar leader Fred Halstead.6

By 1968, however, things had changed. The rising examples of GI protest showed antiwar activists that soldiers could be much more than moral props or objects of sympathy; they could be agents for peace in their own right—a major, dynamic constituency of the antiwar movement. They did need to be organized; indeed, they were already organizing themselves. Moreover, both sides needed each other. The civilian movement created a larger atmosphere for troop resistance and could provide moral and material support. GIs offered the civilian movement a new kind of legitimacy, as well as a strategic front that struck at the heart of the war machine. And by the end of 1967, both sides were building a tighter relationship through common work in urban hubs located near military bases. In San Francisco, for example, a blossoming relationship between antiwar GIs and civilians produced new breakthroughs in creative tactics and solidarity efforts. Perhaps most famously, the October 1968 Presidio Mutiny that involved 27 troops showed the potential for collective GI resistance. Such local developments in the Bay Area would soon go national and even global.

The GI Movement

All of this set the stage for the rise of the GI movement in 1968. The GI movement was a collective effort by soldiers, veterans, and civilian activists to build dissent within the military during the war’s last half-decade. It was united by the common goals of organizing troops, ending the war, fighting racism, and defending troop civil liberties. Most organizing with the GI movement was local, shaped by the conditions soldiers confronted. The different parts of the movement, however, were knitted together through common narratives, symbols, and tactics. The GI movement grabbed media headlines and generated alarm from the military brass. It would be the first time in U.S. history that a mass antiwar movement tried to organize within the military in a sustained way, imagining soldiers as a core constituency for a radical mission of ending the war and re-envisioning foreign policy.

Two organizing breakthroughs in 1968 were crucial to the rise of the GI movement. The first was the rise of GI antiwar coffeehouses. Civilian activists established these venues near military bases to attract and politicize GIs and give them an alternative, countercultural space to gather. These coffeehouses served as centers for local antiwar organizing and helped build solidarity between GIs and civilian activists. The first coffeehouse, called the UFO, opened its doors in early 1968 in Columbia, South Carolina, near Fort Jackson, the army’s largest basic training installation. The UFO was the brainchild of Fred Gardner, an antiwar activist from the Bay Area. Gardner believed that the army “was filling up with people who would rather be making love to the music of Jimi Hendrix than war to the lies of Lyndon Johnson.”7 The UFO aimed to attract these soldiers, and it did so by the hundreds. The example of the UFO inspired others, and coffeehouses quickly spread across the United States and beyond. They soon became targets of repression, sometimes violent attacks, but not before they made an impact in spreading the GI movement.

The second breakthrough was the birth of the GI underground press. These were antiwar newspapers aimed at soldiers that circulated widely throughout the Vietnam-era military. The first GI paper, Vietnam GI, appeared in late 1967, edited by a Vietnam veteran named Jeff Sharlet, and dozens of other papers soon followed. Their titles mocked the military— The Last Harass, A Four Year Bummer, Kill for Peace—and their pages contained uncensored news about the war, heroic reports of GI protest, satiric cartoons that bashed military authority, information on legal help, and letters written by soldiers. More importantly, the production and circulation of the papers provided a common project for dissident soldiers and their allies across the world. Organizers for the GI movement distributed the papers deep into the ranks, and thousands of troops were exposed to their antiwar message. Through the GI press, troops stationed from Europe to Japan and from the United States to Vietnam could plug into the global effort to build soldier opposition to the war.8

With the first coffeehouses and GI papers came a host of new soldier organizations. Scores of dissident troops joined newly formed groups like GIs for Peace at Fort Bliss, GIs United Against the War in Vietnam at Fort Jackson and Fort Bragg, and the Concerned Officers Movement. These organizations engaged in a range of activities, from petitioning and protesting on bases to mobilizing turnout for regional demonstrations. They inevitably faced harassment and punishment, but they used this to build defense campaigns that attracted media attention and popularized soldier protest.

A burgeoning network of civilian support was also central to defending GIs against repression and expanding the GI movement. Campaigns like 1968’s “Summer of Support” and groups like the GI-Civilian Alliance for Peace and the United States Servicemen’s Fund (USSF) spread the word about GI resistance and provided valuable solidarity, from organizers on the ground to material aid. The USSF raised hundreds of thousands of dollars that it distributed to local projects. Organizations like the Pacific Counseling Center and the GI Civil Liberties Defense Committee provided top-notch movement lawyers to defend dozens of antiwar soldiers. All this contradicts the myth of an antiwar movement that hated the troops. In fact, by working together in solidarity, GIs and civilian allies made soldier organizing a key front for the antiwar movement by the end of 1968.

The GI movement continued to grow through 1969 and into the early 1970s. Soldier protest became a ubiquitous part of the peace movement, with thousands of troops involved in mass marches, signing petitions, and small-scale direct actions. For example, 1,365 GIs signed a November 1969 full-page New York Times ad against the war. Hundreds, including those stationed in Vietnam, showed their support for the 1969 Moratorium demonstrations. One soldier wrote from Vietnam to report that “59 Marines and 1 corpsman signed our petition for Xmas moratorium and we have more planned for this month.”9 Another GI wrote from Long Binh to say he was “enlisting the support of the soldiers” and included with his a letter a signed petition that was “simply a statement of support for the Vietnam Moratorium.”10

While thousands of soldiers signed petitions like these during the war, others took more immediate measures. A soldier stationed at “Pig Headquarters, Long Binh” described a Memorial Day event at which “several of the ‘lower EM’ [enlisted men] decided to have a war protest parade in the company area.” Because the “folks at home have the privilege of parading in their hard hats and T-shirts,” he explained, “we felt it was appropriate to express sentiments against the war in the same manner.”11

Troops also defended their civil liberties against military authority. The Uniform Code of Military Justice gave commanders arbitrary power to punish dissenters. Soldiers countered military justice with “GI rights,” a broad defense of the constitutional rights of servicemembers to express their opposition to the war, even as they served. Hundreds of soldiers struggled for their free-speech rights, aided by a legal defense network led by some of the nation’s most prominent attorneys. Soldiers in Vietnam invoked the language of rights as they complained of the invasiveness of military authority and its erosion of their morale.

Vietnam was a working-class war, and most of the soldiers who resisted were the rank-and-file troops who bore its greatest burdens. In opposition to the “lifers” up top, soldiers formed groups, even unions, animated by the concerns and consciousness of the lower ranks. The class structure of the military was also deeply racialized. Top commanders were mostly white, while black GIs fought and died in disproportionate numbers and suffered an excessive amount of Article 15s, courts-martial, and other punishments. This racism existed against a backdrop of rising black political radicalism, with figures like Malcolm X and the Black Panthers serving as inspiration for young troops. Black GIs formed anti-imperialist organizations like the Unsatisfied Black Soldiers in West Germany and the Movement for a Democratic Military in California. They refused riot duty, wore African medallions, raised their fists in Black Power salutes, and sometimes spearheaded efforts at interracial GI organizing.

The depth and breadth of soldier dissent is seen most fully in the GI underground press. By the turn of 1970, scores of antiwar papers were circulating among thousands of soldiers throughout the military. Hundreds of troops took it upon themselves to order bundles of these papers and distribute them across the globe. In 1971 several GIs wrote to the Ally from Vietnam: “We, the undersigned…would like as many copies[,] over a hundred [if] possible,” and said the papers would “be distributed between two companies here in Chu Lai.”12 The Ally and other GI papers received hundreds of letters like this, and they offer a glimpse of how troops brought the antiwar press deep into their ranks. Producing, circulating, reading, and writing to GI papers were central unifiers for troop resistance from the United States to Europe and Japan to Vietnam. The pages of these papers contained news and analysis about the war and GI resistance around the world, and through them soldiers saw themselves as part of a wider movement.

In addition to distributing papers as a form of movement-building, GIs wrote them thousands of letters that reveal much about the hidden world of Vietnam-era soldier resistance. These letters captured the antiwar, countercultural politics of many troops, and described the tension on the ground between GIs and higher-ups. A Marine stationed in Chu Lai wrote that he had “a lot of people behind him” when he complained that “the pigs keep fucking with us and pulling their petty shit” because our “hair to [sic] long, mustache not trimed [sic] like Hitler…, living area not clean, for wearing peace medallions or beads…for having a peace symbol in your hooch.”13 Letters also hinted at collective solidarities among GIs. Some described group actions or were signed by multiple troops. Nearly a dozen soldiers signed a 1970 letter from Vietnam that declared: “We have all been fucked in some way by this Army. All of us would like to distribute copies of your paper. Some of us are draftees, the others enlistees, but we all agree that this war is immoral.”14

Meanwhile, coffeehouses and movement centers continued to spread. By 1971, close to two dozen had appeared across the United States, Western Europe, and the Pacific Rim. These continued to be hubs for organizing and the cultivation of GI-civilian solidarity that resisted the war and the military. Thousands of soldiers visited these establishments. Vibrant communities of resistance from Killeen, Texas, to Mountain Home, Idaho, sustained antiwar protest that brought the peace movement to military bases and towns. Even more, GI protest had gone truly global, with organizing efforts everywhere from West Germany to Japan to England to the Philippines, and even at obscure bases in Iceland, Turkey, and Spain. Soldiers and their allies imagined these local activities as parts of a worldwide GI rebellion.

The U.S. radical left played an important role in the GI movement. Enlisted “GI organizers” connected to civilian radicals fomented troop dissent with an impact that belied their small numbers.15 Politically driven and backed by networks of savvy activists, these troops were a vanguard within the ranks that played a catalyzing role analogous to left-wing CIO militants of the 1930s. Some had links to left groups who provided material aid and ideological motivation. Andy Stapp, for example, was associated with Youth Against War and Fascism; Private Joe Miles, who organized dozens of troops at Fort Jackson to defend GI rights, was a member of the Young Socialist Alliance. Radical allies mobilized the “Legal Left” to defend persecuted troops, continuing a tradition of mass defense campaigns that went back to Sacco and Vanzetti. The legacies of the left’s role in the GI movement were mixed: sectarianism, opportunism, turf battles, alienating rhetoric, and patronizing behavior towards troops were all persistent problems. But radical leftists also played an indispensable role in providing political will and tireless organizing efforts.

The breadth and dynamism of the GI movement was displayed on May 15, 1971, when antiwar troops turned the traditional Armed Forces Day into what they called Armed Farces Day. Creative protests involving hundreds of troops occurred at nineteen separate military installations, in some cases forcing commanders to cancel their planned festivities.16 Dissent extended into the Air Force and especially the Navy. In 1971 the “SOS Movement” (Save Our Sailors) spread across the California coast, with hundreds of soldiers and civilians organizing in attempts to prevent the U.S.S. Constellation and Coral Sea from sailing to Vietnam. Throughout all this, the self-activity that fueled the GI movement continued: sailors agitated and conspired below deck; troops staged ad hoc protests in their company areas in Vietnam; African American soldiers held anti-racist rallies in West Germany.

In Vietnam

The GI movement was an organized expression of a much larger reservoir of troop discontent. By the early 1970s, the military in Vietnam was ridden with decentralized rebellion. Many combat troops felt that the unpopular war “wasn’t worth it,” and they saw themselves being used as “pawns” and “bait” in a “lifer’s game” of career advancement. To stay safe and sane, troops developed what Fred Gardner called a “vague survival politics” that responded to the immediate dangers they faced in Vietnam. These tactics became weapons that grunts used to exert bottom-up power to protect their bodies and minds as they waited out the war.17

The starkest form of survival politics was outright refusal of combat orders, but such mutiny was rare. More common were maneuvers to avoid combat without openly risking punishment. Soldiers used the “search-and-evade” tactic, in which they pretended to obey fighting orders while secretly avoiding armed contact. One veteran explained that his unit would “go a hundred yards, find us some heavy foliage, smoke, rap and sack out.”18 Combat avoidance was “virtually a principle of war” by late 1971. Troops also sabotaged military equipment: gears were jammed on ships and fires mysteriously broke out on deck, which prevented embarking to Vietnam.

The most violent form of revolt was “fragging,” or the attempted murder of higher-ups. Nearly 600 instances were reported between 1969 and 1971, though more likely went unreported. Some fragging attempts happened in the field but many occurred in the rear, often because of anger over punishment for drugs or racial tensions. One GI called fragging “the standard response of the Army’s little people” to “any action directed by their superiors that they consider unnecessary harassment.” Actual fraggings could take the form of a grenade explosion or feigned friendly fire, but more important was the widespread knowledge that they could happen. The practice of fragging, said one officer, was “troops’ way of controlling officers,” and it was “deadly effective.”19 While brutal, fraggings grew out of the surreal atmosphere of the war and its normalized violence. They reflected the disintegration of the late Vietnam-era army and the fact that some GIs saw their main conflict with the military rather than the Vietnamese.

Soldiers in Vietnam also waged a cultural rebellion that drew on the symbols and language of the 1960s counterculture. They grew their hair out and wore protest decorations. They etched peace signs and psychedelic art on their Zippo lighters, along with slogans like “Pray for peace and put a Lifer out of a job,” and “We are the unwilling led by the unqualified doing the unfortunate for the ungrateful.” They used drugs to relax and escape the stress of war, and GI “heads” celebrated getting high as a rejection of the war and the army’s authoritarianism. This GI counterculture was also a rank-and-file class culture. The rebellious identities that soldiers asserted were distinctly those of the lower ranks, of the grunts who performed the thankless labor of the war while, as they saw it, uptight lifers sat in air-conditioned buildings barking out orders.

One measure of the depths of GI rebellion is the deep sense of alarm that it generated among military and political elites. Congress devoted hours of hearings in the early 1970s to the investigation of radical subversion in the armed forces. Military intelligence closely monitored the activities of the GI movement, and even General Westmoreland worried about the GI coffeehouses. Army leaders openly lamented the scope of the crisis. Most famously, the celebrated military historian Colonel Robert D. Heinl published an article in the June 1971 edition of the Armed Forces Journal titled “The Collapse of the Armed Forces.” It began with the stunning words: “The morale, discipline and battleworthiness of the U.S. Armed Forces are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at any time in this century and possibly in the history of the United States.” Over the next twenty pages, Heinl elaborated in grim detail the breakdown of the military: the disintegration of discipline, the spread of dissent, and the unraveling of morale.20

The media echoed this sense of crisis. “Not since the Civil War,” stated the Washington Post in 1971, “has the Army been so torn by rebellion.” In 1970, Newsweek wrote of “the New GI” who opposed the war, embraced the counterculture, and identified with protest politics. These soldiers were “young antiwar warriors” who “flout[ed] the conventional ‘my-country-right-or-wrong’ military values of yesteryear” and “prefer[ed] pot and peace posters to the beer and pin-ups of their more traditional comrades.” The crisis in the military that these “New GIs” created would soon lead elites to completely overhaul the armed forces.21

Decline

As much as it thrived, the GI movement also faced serious obstacles, and several factors contributed to the decline of soldier resistance in the early 1970s. While many troops sympathized with the antiwar movement, most declined to actively participate. Speaking out was risky, with harassment and punishment, even a dishonorable discharge, awaiting dissidents. Moreover, involvement was unstable even for those that joined the GI movement. The military regularly transferred soldiers, and the grind of service could isolate and wear down individuals. Thousands of soldiers participated or sympathized with antiwar protest, but the finite nature of enlistment—the incentive to suck it up, wait it out, and get out—and the levers of military justice militated against many GIs acting on their beliefs.

Outright repression also hampered the GI movement. Local police and military intelligence closely monitored coffeehouses, and they were targeted with fines, arrests, and even paramilitary violence. Bullets were shot through the Shelter Half in Tacoma; the Covered Wagon in Idaho was firebombed. Soldiers who received and distributed GI papers had their mail read. Protesters were given Article 15 punishments, courts-martial, or thrown into the stockade. GIs knew that association with dissent invited unpleasant consequences.

Left sectarianism also hurt the GI movement. Some coffeehouses were taken over by tiny groups and turned into recruitment operations. Competing sects theorized GIs as the potential vanguard of their hoped-for revolutionary movements. Their dogmatic style limited the reach of local GI movements and created, as one report stated, “an atmosphere that many people can’t relate to.”22 The radical politics of organizers could be an asset, but the tactical errors of some and their often condescending attitude towards soldiers contributed to the failure of a dynamic, sustainable coffeehouse project that could draw on GI self-activity.

Most crucial was the winding down of the war itself in 1972 and 1973. Steady combat troop reduction and the end of the draft stemmed the channeling of social unrest into the ranks. GI organizing efforts continued into the late 1970s, but they were never able to achieve previous levels of success. When the ordeal of the Vietnam War ended, so did the conditions that bred the possibility of a large wave of GI dissent.

Legacies

Nearly a half-century later, what are the legacies of Vietnam-era GI resistance? First, dissident troops helped create a crisis within the military that ultimately contributed to the end of the draft and the war. With the rise of the All-Volunteer Force in the 1970s and 1980s, elites overhauled the military for a post-Vietnam, neoliberal era. It is also worth noting that protest by black GIs during the Vietnam War catalyzed substantial reforms within the armed forces to integrate the higher ranks and deal the final death blow to the Jim Crow army.

Second, Vietnam left a model of resistance for later generations. Since 2003, Iraq and Afghanistan veterans have been inspired by the example of the GI movement. They have linked up with Vietnam-era movement veterans and borrowed many of their tactics, from public testimony and agitprop actions to coffeehouses and antiwar papers. The precedent of Vietnam-era GI resistance and the preservation of its memory helped pave the way for the current era of troop dissent.

Third, the history of the GI movement debunks the widespread trope of a civilian peace movement that hated U.S. troops. This has long been the most potent myth aimed at discrediting the antiwar left and inciting support for militarist ventures. It is important to remember that the antiwar movement’s orientation towards Vietnam-era GIs was mostly one of sympathy and solidarity. Antiwar activists saw troops as exploited by a deceptive political class and a draft rigged by class and race. They sought to help them and organize them to defend their rights and end the war. Many troops saw the antiwar movement, not the war’s backers, as their biggest ally. As one soldier put it in a letter: “We troops here in Vietnam are against the war and the demonstrations in the states do not hurt our morale. We are very glad to see someone cares and is working to bring us home.”23

This brings us to a final point. Hegemonic “common sense” rests in part on political constructions of historical memory and popular icons. The soldier is a powerful cultural figure that has been defined by a linkage between knee-jerk support for “the troops” and uncritical support for war-making, military spending, and an emotional investment in a culture of militarism. The historical erasure of soldier protest has aided both conservative reaction and liberal militarism in marginalizing left dissent and simplistically pitting middle-class protesters against working-class troops.24 The history of Vietnam-era GI resistance is a vital counter-memory that reminds us that many troops were not against protesters, but that they were the protesters; that the civilian antiwar movement didn’t spit at soldiers but rather oriented towards them with sympathy and solidarity; that thousands of working-class troops stood for peace over war and militarism; and that it was the war and the military, not antiwar protesters, that demoralized many GIs fighting in Vietnam. This is important history to remember if the left is to challenge the dominant myths that continue to underpin a culture of military aggression.

Notes

On the spit-upon veteran myth and other tropes used to discredit the antiwar movement and the left, see Jeremy Lembcke’sThe Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam(New York: NYU Press, 2000) and H. Bruce Franklin’sVietnam and Other American Fantasies(Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001).

On the spit-upon veteran myth and other tropes used to discredit the antiwar movement and the left, see Jeremy Lembcke’sThe Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam(New York: NYU Press, 2000) and H. Bruce Franklin’sVietnam and Other American Fantasies(Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001). See Christian Appy’sWorking-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), chapter 1.

See Christian Appy’sWorking-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), chapter 1. Haynes Johnson and George C. Wilson,Army in Anguish (New York: Pocket Books, 1972), 73.

Haynes Johnson and George C. Wilson,Army in Anguish (New York: Pocket Books, 1972), 73. Andy Stapp,Up Against the Brass (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1970) and “Exclusive!: The Plot to Unionize the U.S. Army,”Esquire, August 1968.

Andy Stapp,Up Against the Brass (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1970) and “Exclusive!: The Plot to Unionize the U.S. Army,”Esquire, August 1968. “Two Marines Test Right of Dissent,”New York Times, March 7, 1969.

“Two Marines Test Right of Dissent,”New York Times, March 7, 1969. Fred Halstead,Out Now!: A Participant’s Account of the American Movement Against the Vietnam War(New York: Monad, 1978), 173.

Fred Halstead,Out Now!: A Participant’s Account of the American Movement Against the Vietnam War(New York: Monad, 1978), 173. Fred Gardner, “Hollywood Confidential: Part I,” in Viet Nam Generation Journal Online 3, no. 3.

Fred Gardner, “Hollywood Confidential: Part I,” in Viet Nam Generation Journal Online 3, no. 3. For more on the GI underground press, see Derek Seidman, “Paper Soldiers: The Ally and the GI Underground Press” inProtest on the Page: Essays on Print and the Culture of Dissent (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2015).

For more on the GI underground press, see Derek Seidman, “Paper Soldiers: The Ally and the GI Underground Press” inProtest on the Page: Essays on Print and the Culture of Dissent (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2015). S.R. to theAlly, February 7, 1970, Box 2 Folder 6, Clark Smith Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society [WHS].

S.R. to theAlly, February 7, 1970, Box 2 Folder 6, Clark Smith Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society [WHS]. Long Binh Post, October 28, 1969, Vietnam, Vietnam Moratorium Committee Records, Box 1 Folder 7, WHS.

Long Binh Post, October 28, 1969, Vietnam, Vietnam Moratorium Committee Records, Box 1 Folder 7, WHS. Sp4 “Getting Short and Getting Out” to theAlly, n.d., Box 2 Folder 1, Clark Smith Collection, WHS.

Sp4 “Getting Short and Getting Out” to theAlly, n.d., Box 2 Folder 1, Clark Smith Collection, WHS. R.M, S. C. K., and F.J.H. to theAlly, January 3, 1971, Box 2 Folder 6, Clark Smith Collection, WHS.

R.M, S. C. K., and F.J.H. to theAlly, January 3, 1971, Box 2 Folder 6, Clark Smith Collection, WHS. The Gremlin to theAlly, n.d., Box 2 Folder 5, Clark Smith Collection, WHS.

The Gremlin to theAlly, n.d., Box 2 Folder 5, Clark Smith Collection, WHS. 86th Maint. BT to theAlly, June 20, 1970, Box 2 Folder 3, Clark Smith Collection, WHS.

86th Maint. BT to theAlly, June 20, 1970, Box 2 Folder 3, Clark Smith Collection, WHS. “GI Organizer” was a term used by Lawrence Radine inThe Taming of the Troops: Modernizations in Social Control in the U.S. Army (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1974), chapter 1.

“GI Organizer” was a term used by Lawrence Radine inThe Taming of the Troops: Modernizations in Social Control in the U.S. Army (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1974), chapter 1. David Cortright,Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance during the Vietnam War(Chicago: Haymarket, 2005), 82–83.

David Cortright,Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance during the Vietnam War(Chicago: Haymarket, 2005), 82–83. Fred Gardner, “War and GI Morale,”New York Times, November 21, 1970, 31.

Fred Gardner, “War and GI Morale,”New York Times, November 21, 1970, 31. “The Troubled U.S. Army in Vietnam,”Newsweek, January 11, 1971.

“The Troubled U.S. Army in Vietnam,”Newsweek, January 11, 1971. “Fragging and Other Symptoms of Withdrawal,”Saturday Review, January 8,1972.

“Fragging and Other Symptoms of Withdrawal,”Saturday Review, January 8,1972. Col. Robert D. Heinl, Jr., “The Collapse of the Armed Forces,”Armed Forces Journal, June 7, 1971.

Col. Robert D. Heinl, Jr., “The Collapse of the Armed Forces,”Armed Forces Journal, June 7, 1971. “Army Seldom So Torn By Rebellion,”Washington Post, February 10, 1971; “The New GI: For Pot and Peace,”Newsweek, February 2, 1970, 24.

“Army Seldom So Torn By Rebellion,”Washington Post, February 10, 1971; “The New GI: For Pot and Peace,”Newsweek, February 2, 1970, 24. “Report From the Fort Bragg Collective (Haymarket Square Coffeehouse),” Box 1, Folder “Project Description (Internal),” David Cortright Collection, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

“Report From the Fort Bragg Collective (Haymarket Square Coffeehouse),” Box 1, Folder “Project Description (Internal),” David Cortright Collection, Swarthmore College Peace Collection. “Dear People”, October 23, 1969, Student Mobilization Committee Collection, Box 2 Folder 6, WHS.

“Dear People”, October 23, 1969, Student Mobilization Committee Collection, Box 2 Folder 6, WHS. On the construction of the middle class protesters versus working class pro-war troops trope, see Penny Lewis,Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks: The Vietnam Antiwar Movement As Myth and Memory (Ithaca, NY: ILR, 2013). I borrow the term “countermemory” from Lewis.

On the construction of the middle class protesters versus working class pro-war troops trope, see Penny Lewis,Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks: The Vietnam Antiwar Movement As Myth and Memory (Ithaca, NY: ILR, 2013). I borrow the term “countermemory” from Lewis.