Workers Vanguard No. 1165

|

15 November 2019

|

| |

Down With School Segregation, Legacy of Slavery!

Part One

We print below, edited for publication, a presentation by comrade L. Singer at a Spartacist League forum held in Chicago on October 26. It was first given in Brooklyn, New York.

Under the reactionary Trump presidency, which revels in unabashed bigotry, there has been a lot of feigned concern in the liberal, pro-Democratic Party bourgeois press about the perils of racism. In the past year, numerous articles reported that New York City has some of the most segregated schools in the U.S. and that only seven black students got into Stuyvesant this year. Stuyvesant is the top elite public high school in NYC that admits 900 kids out of a school system of more than a million students. Mayor Bill de Blasio, a so-called “progressive” Democrat, and schools chancellor Richard Carranza have postured as being for integration, proposing a few token changes that have been met with a vicious backlash. De Blasio had suggested phasing out the racist test that determines admission to the elite schools, proposing to let in the top 7 percent of students from every middle school. Predictably, the mayor abandoned this proposal.

Meanwhile, the same newspapers that claim to be so concerned about school segregation, like the cynical mouthpiece of the ruling class, the New York Times, publish scare articles about other tokenistic proposals, like the idea of getting rid of the elementary school Gifted & Talented programs. Journalist Jelani Cobb aptly described this alarmist campaign as making it sound as if de Blasio was declaring war on smart children. The point is to all but ensure that no change ever happens. Of course, we would support any measure that would provide even a scrap of greater access to quality education. But these plans will not affect the vast majority of NYC students, who would still be confined to underfunded and overcrowded schools that are little more than holding pens, complete with metal detectors, surveillance cameras and “zero tolerance” discipline enforced by armed NYPD cops.

By the way, I have a daughter who is in the Gifted & Talented program in her district. (There are multiple districts within almost every borough.) There are only a few G&T classes of about 35 kids for the entire district of over 30,000 students, and while the district is roughly 15 percent black, there is not one black student in her class. This one “gifted” class is in a school that is 80 percent non-white. If you don’t get into the class when you’re four years old, admission being based on a single test, it’s unlikely you ever will. Meanwhile, the same district has a 70 percent white school that is much better funded. Getting to go there depends on where you live. Parents in that zone don’t need to worry about kids getting into the G&T program because their school is better. So, getting rid of the G&T would actually do little to change the overall racial segregation of the schools. But even little things elicit a big racist furor.

NYC public schools are 70 percent black and Latino. While 43 percent of the city’s population is white, only 15 percent of the public school student body is. And much of that 15 percent goes to the best public schools, where the students are mostly white, while over 70 percent of black and Latino students go to schools that are less than 10 percent white. In NYC, a bastion of enlightened liberalism presently run by the Democrats, as is usual, there are two separate systems of education. Where a student ends up is largely determined by race and class. This is true all over capitalist America. And while New York has its particularities and special means by which schools are segregated, in every major city in the U.S. the reality of segregated education persists and has even worsened in the last few decades. So here we are, 65 years after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision and over 150 years after the victory of the North in the Civil War. So, why are schools still segregated?

As Marxists, we understand that black oppression is the cornerstone of American capitalism, a system built from colonial times on the backs of black slaves. This point is fundamental. In this racist, class-divided society, a tiny handful of people own the banks and industry. It is labor power—the sweat and blood of the working class—that is the source of the capitalists’ profits. Black people are specially oppressed as a race-color caste, segregated in the main at the bottom of society and confronted every day with the legacy of chattel slavery. Racial oppression is ingrained in the U.S. capitalist economy and every social institution. Anti-black racism is ruthlessly promoted by the ruling class to keep the working people divided and to conceal their common class interests against the exploiters.

An expression of black oppression in America is the racist rulers’ conscious and systematic denial of quality education to the mass of the black population. The capitalist class hoards the vast wealth of society for themselves. They run the education system to serve their interests, including by promoting bourgeois ideology. The elite schools are intended to prepare the next generation of technocrats, bureaucrats and CEOs. When it comes to the working class and the poor, including whites, the capitalists seek to spend on education only what they think they can realize back in profit from exploiting labor, and they also use the schools for military recruitment. The racist rulers see little use in educating the majority of black and Latino youth because as capitalism decays, it has no decent jobs for them to fill. The lives of the ghetto and barrio poor have already been written off as expendable, leaving them to die on the streets or to be thrown behind bars as millions have been.

The truth is that no reform under capitalism can fundamentally transform the social conditions that continue to imprison the impoverished black masses. The lack of affordable, quality housing is directly connected to the hellish conditions of the schools. Both are endemic to the capitalist profit system. Only the working class has the social power and class interest to wage an uncompromising struggle for quality, integrated education and housing for all. To win full political, social and economic equality for black people requires that the multiracial working class rip the economy out of the hands of the capitalists and reorganize it on a socialist basis, so that production is for human need, not profit. In order to wage this revolutionary struggle, the working class must become the champion of black equality. This also means organizing politically in opposition to all the agencies of the class enemy. The illusions that working people and minorities have in the Democratic Party of racist capitalism and war are a deadly obstacle to the struggle.

That’s my second fundamental point. The Democratic Party, which postures as the friend of workers, black people and all the oppressed, is in fact their class enemy. All the Democrats, including those calling themselves “progressive,” represent the capitalist class and defend its interests. In recent decades, the Democrats, just as much if not more than their Republican counterparts, have maintained segregation in education and have made it, if anything, worse. The bipartisan attacks on public education have gone hand in hand with decades of sustained capitalist onslaught against the living standards of the working class. In the face of this unrelenting class war, the pro-capitalist union misleaders have accepted giveback after giveback, while binding workers to the Democrats. It is vital to replace these labor traitors with a leadership committed to political independence of the working class.

This leads me to my third fundamental point: the need for a revolutionary vanguard party. Central to the program of such a party must be the fight for revolutionary integrationism. This is counterposed to liberal integrationism—the idea that integration and equality can be achieved by reforms under capitalism. Liberal integrationism is basically a lie that amounts to prettifying the brutal reality of racial oppression. Revolutionary integrationism is also counterposed to all forms of black separatism, which, at bottom, are expressions of despair over the prospects for integrated class struggle. Our task is building a revolutionary party that arms the working class with the consciousness that the fight against black oppression is central to the fight to emancipate labor and all the oppressed from the bondage of capitalist exploitation.

The grotesque inequality between the filthy rich and the poor that is seen in all decaying capitalist societies is particularly acute in New York, the center of U.S. finance capital. When de Blasio ran for mayor, he did so promising to tackle inequality, much in the same manner as we see with Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in the current presidential campaign. At that time, a lot of reformist leftists were pushing illusions in de Blasio. His “tale of two cities” campaign slogan tapped into real anger among the vast majority in the city who suffered under ex-mayor Michael Bloomberg’s rule. An actual capitalist worth more than $50 billion, Bloomberg and his Wall Street cronies swam in profits, while most everyone else either treaded water or sank deeper into poverty. He attacked the city unions, including calling transit workers “thugs” when they dared to strike in 2005. He closed schools in black and Latino neighborhoods and pushed anti-union charters, installing the citywide system of “school choice,” a fraud that led to even greater segregation of schools.

But de Blasio in office has shown time and again that, like those before him, he is the mayor of Wall Street, ruling on behalf of the financial titans who lord it over the working class—white, black, Latino, Asian and immigrant. Under de Blasio’s reign, billions have been dished out by the city to real estate magnates who throw up luxury skyscrapers, while slumlords hike up rents and drive working people and the poor out of gentrifying neighborhoods. As the homeless population in NYC continues to grow, one out of ten public school students is in temporary housing, including homeless shelters.

Admission to elementary schools is mostly tied to residential districts, and housing in New York City is segregated. In addition, the best middle schools and high schools have other means of keeping black and Latino kids out, including through screening for test scores, absences and lateness. You can have multiple segregated schools in one building. For example, at the John Jay educational complex in posh Park Slope, Brooklyn, there are four high schools, three of which are roughly 90 percent black and Latino. The other school, Millennium, is only 40 percent black and Latino and gets vastly more funding. One parent said: “It’s a Jim Crow system in Brooklyn in 2017.” That same year, after one of the high school principals, Jill Bloomberg (no relation to the other Bloomberg), tried to address segregation at her school and the greater resources allotted to Millennium, she was, no joke, investigated for “communist organizing.” The investigation was eventually dropped. But it testifies to how little has changed and why when the issue of integration is raised, so is the specter of communism.

Finish the Civil War!

When you touch integration, you are touching the question of revolution and the unfinished business of the Civil War. To understand why black youth, and increasingly Latinos, are by and large sent to unequal and inferior schools, one needs to understand the legacy of slavery in this country and that black people today constitute a race-color caste. This caste status was consolidated in the aftermath of the defeat of Reconstruction, so it’s crucial to know that history as a means to understand the present and the way out for the future.

American capitalism was founded on black chattel slavery. The consolidation of slavery gave rise to the concept of what was known as the “Negro” and “white” races. While the idea that there are different races is scientific nonsense, it is a social fact essential to understanding this society. The color line, developed to justify slavery, became permanent and hereditary. Black slaves remained black slaves, as did their children and grandchildren. The peculiar “principle” that in the U.S. determined who would be a slave was the “one drop” rule—one drop of “black” blood makes you black.

The veteran Trotskyist Richard Fraser underscored in his writings some 60 years ago how the concept of race was central to the development of American capitalism. He outlined how the material basis of black oppression drew upon a precapitalist system of production. Slavery played a key role in the development of British industrial capitalism and U.S. capitalism. British textile owners received Southern cotton, which was handled by powerful New York merchants. Those merchants sold manufactured goods to the South.

Although slavery and capitalism were intertwined, they were different economic systems. The Southern plantation system acted as a brake on the growth of industrial capitalism. Throughout the period between the American Revolution and the Civil War, repeated “compromises” sought to offset what was called the “irrepressible conflict” between the North and South. However, each compromise only delayed the inevitable conflict and further entrenched the power of the slavocracy. It took a civil war to smash the slavocracy. The North’s victory was made possible only through the emancipation of the millions of black chattel slaves and the arming of 200,000 free black men and former slaves in a war that destroyed the slave system. There are many good articles on this history in our Black History and the Class Struggle pamphlet series.

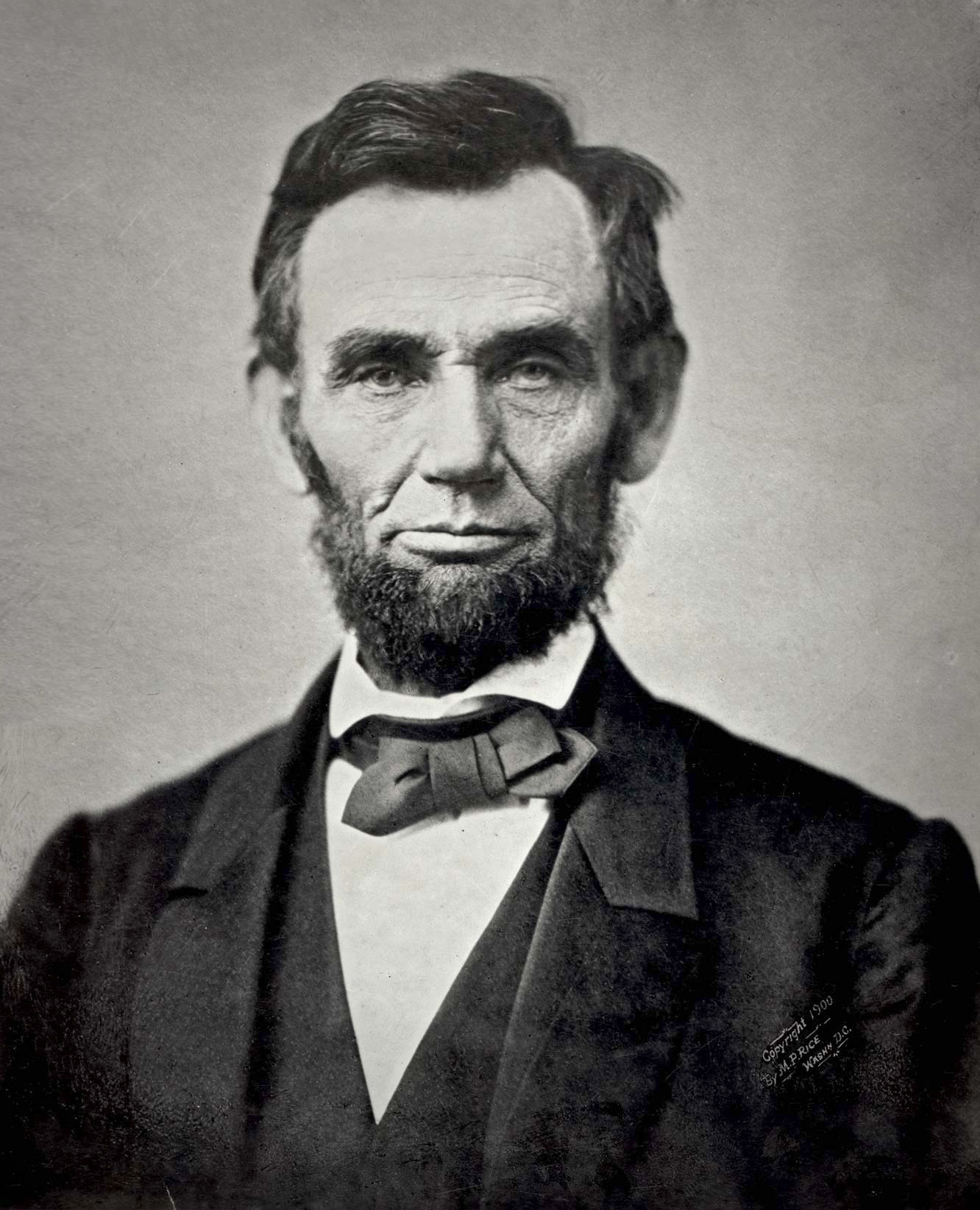

On the eve of the Civil War, 90 percent of black people in the U.S. were enslaved, with nearly half the free blacks living in the North. Most of the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision deals with whether black people who were not slaves were citizens of the United States. As Chief Justice Roger Taney, a white-supremacist, put it:

“The question is simply this: Can a negro whose ancestors were imported into this country and sold as slaves become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guarantied by that instrument to the citizen, one of which rights is the privilege of suing in a court of the United States in the cases specified in the Constitution?”

And Taney continued that black people “had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” In other words, black people in the U.S. would forever be marked as inferior because their ancestors had been slaves. The Dred Scott decision would reverberate over and over, and still does today, as a definition of race-color caste oppression.

The fight for education has always been a hallmark of struggles by the oppressed for freedom. In the pre-Civil War South, slaves who dared to learn to read met the lash of their masters’ whips; those who dared to teach them faced imprisonment or met a worse fate at the hands of lynch mobs. Before the 19th century, only South Carolina and Georgia explicitly forbade the teaching of blacks. But the slaveowners learned from the example of slave uprisings in the Western Hemisphere, particularly the Haitian Revolution, which achieved independence for Haiti in 1804. The successful uprising in Haiti, as well as the Gabriel Prosser and Denmark Vesey insurrectionary conspiracies and the Nat Turner revolt, were all organized and led by literate blacks. Laws were passed in all states south of the Mason-Dixon line making it a crime to teach a slave to read or write.

For Frederick Douglass, who fought his way out of slavery and became a political leader of the radical left wing of the abolitionist movement, there was great motivation to educate himself, no matter the cost. He wrote: “‘Very well,’ thought I. ‘Knowledge unfits a child to be a slave.’ I instinctively assented to the proposition, and from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom.”

It’s a common view in this country that the South was the seat of American barbarism, while enlightenment was to be found in the North. In reality, the South—because it is where slavery was dominant and where the overwhelming majority of black people lived after emancipation—represented a concentrated expression of the deep racist prejudice that permeated the whole country. Many of the concepts associated with the South originated in the North, found full fruition in the South and were exported back to the rest of the country. Segregation was no less deeply entrenched in the North than in the South. After the American Revolution, the idea of public schools began to take greater hold, coinciding with the expanding capitalist system’s need for basic education of workers. These were called common schools at the time, and in the North they were mostly not open to free blacks, and definitely not to slaves.

While slavery was abolished in most Northern states in the 1820s, these states offered little access to education for blacks. In most major cities, if there was any educational opportunity for black youth, it was in segregated schools. These were not public schools, but schools funded primarily by abolitionists and Quakers.

In some small communities in the North, black children were allowed to attend predominantly white local schools, but they were segregated. In a book I read on this history, a black man described what it was like going to school in Pennsylvania at that time, when black children were not allowed to drink from the same bucket or cup as the white children and had to sit back in the corner away from the fire no matter how cold the weather might be. This treatment of free black people in the North was an early example of caste subjugation: a population—officially free and not slave—could be segregated, discriminated against, and at times violently attacked, for no reason other than their skin color.

It wasn’t until the 1830s that major cities in the North started public schools for black youth, and these schools were inferior. Black parents called these schools “caste” schools. In Boston in 1848, a black printer, Benjamin Roberts, wanted his five-year-old daughter to attend the school closest to their home, which was a white school. Roberts sued the city of Boston on behalf of his daughter. His attorney was abolitionist Charles Sumner, assisted by Robert Morris, one of the nation’s first black attorneys. Sumner argued that segregation was a violation of the Massachusetts constitution and “equality under the law.” He argued that “the separation of children in the public schools of Boston, on account of color or race, is in the nature of caste, and is a violation of equality.” In response, Judge Shaw’s ruling against Roberts states: “It is urged, that this maintenance of separate schools tends to deepen and perpetuate the odious distinction of caste, founded in a deep-rooted prejudice in public opinion. This prejudice, if it exists, is not created by law, and probably cannot be changed by law.”

This 1848 ruling would later be cited in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case to show the compatibility of segregation and a mandate of equality before the law. In Rochester, New York, Frederick Douglass’s young daughter Rosetta applied in 1849 to a private school. She was admitted, but she was told she wasn’t allowed to be in the same room with white students. Douglass objected, but he ended up having her privately tutored. In Illinois in 1849, the state legislature provided for state-supported public schools for the first time, but voted for them to exclude black children.

One of the most profound gains resulting from the defeat of the slavocracy in the Civil War was the establishment of a system of public education for all, black and white. V.I. Lenin, the revolutionary Bolshevik leader, noted in “The Question of Ministry of Education Policy” (1913):

“America is not among the advanced countries as far as the number of literates is concerned. There are about 11 per cent illiterates and among the Negroes the figure is as high as 44 per cent. But the American Negroes are more than twice as well off in respect of public education as the Russian peasantry. The American Negroes, no matter how much they may be, to the shame of the American Republic, oppressed, are better off than the Russian peasants—and they are better off because exactly half a century ago the people routed the American slave-owners, crushed that serpent and completely swept away slavery and the slave-owning state system, and the political privileges of the slave-owners in America.”

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Workers Vanguard No. 1166

|

29 November 2019

|

| |

Down With School Segregation, Legacy of Slavery!

Part Two

We print below, edited for publication, the second part of a presentation by comrade L. Singer at a Spartacist League forum held in Chicago on October 26. The talk was first given in Brooklyn. Part One appeared in WV No. 1165 (15 November).

Most of the first free public schools in the South were established after the Civil War and during Radical Reconstruction, the turbulent decade of Southern interracial bourgeois democracy. The freedmen and their white allies were protected by federal troops, many of them black. The Reconstruction Acts, passed by Congress in 1867, mandated the military occupation of the ex-Confederate states and provided for universal common school education. The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868; this stated that everybody born in the U.S. was a citizen, invalidating the Dred Scott decision. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified, granting the right to vote to all male citizens. Black people who served in the Union Army were among the principal leaders of Reconstruction governments and fought tenaciously against segregation.

Thousands of public schools were built, to the enormous benefit of black people and poor whites, although the schools largely remained segregated by race. Some 1,500 schools were built in Texas alone by 1872, and by 1875 half of all children in Mississippi, Florida and South Carolina were attending school. The freedmen’s drive for education for themselves and their children was insatiable, as it was viewed as a path out of conditions of servitude. Thousands of Northern teachers, black and white, flocked to the South to aid the freedmen and were themselves often the target of violence by racists.

There were some attempts to desegregate schools. One effort was led by Robert Smalls, who had earned fame as a slave in 1862 by commandeering a heavily armed Confederate ship in Charleston harbor. He delivered it to the Union fleet, bringing himself and 16 other slaves to freedom. After the war, Smalls was elected to the new South Carolina government. He pushed through legislation to desegregate schools in the state. But when the first black student entered the University of South Carolina, the teachers resigned and the entire student body left the school! In New Orleans in the early 1870s, there was even a brief experiment with integrated public schools. In January 1866, the New Orleans Tribune, the first black daily newspaper in the U.S., published the headline: “All children, without discrimination, will sit together.”

But widespread and violent opposition to “race mixing” ensured that the majority of Southern schools were segregated, and it goes without saying that the black schools were inferior. While abolitionists opposed the heinous institution of slavery, many saw full equality for black people as a whole different matter. As I noted earlier, prior to the Civil War, systematic segregation had taken root in the North, where a fight against the color line was also waged. Radical abolitionist Charles Sumner, in every Congressional session from 1870 until his death four years later, fought against Jim Crow, which he termed “the last tinge of slavery.” Civil War hero Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson was ejected from a local school board in 1869 for demanding an end to segregated schools in Rhode Island.

Frederick Douglass powerfully argued the case for integration, especially as a basis for unity of poor whites and blacks against their common enemy: “The cunning ex-slaveholder sets those who should be his enemies to fighting each other and thus diverts attention from himself. Educate the colored children and white children together in your day and night schools throughout the South, and they will learn to know each other better, and be better able to cooperate for mutual benefit.”

Reconstruction was the first attempt in this country to create a society in which black and white people were equal citizens—which flew in the face of all U.S. history. While Reconstruction is usually viewed as an issue of black and white, the defeat of the slavocracy also accentuated class differences among Southern whites. Democratic Party appeals to white supremacy were a way to block unity between poor whites and blacks. There was no real labor movement in the U.S. before the Civil War. However, it came on the scene afterwards; strikes and other labor protests became widespread. By 1868, the federal government conceded the eight-hour day to federal workers. Karl Marx captured the scene in the first volume of Capital (1867):

“In the United States of North America, every independent movement of the workers was paralysed so long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic. Labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded. But out of the death of slavery a new life at once arose. The first fruit of the Civil War was the eight hours’ agitation, that ran with the seven-leagued boots of the locomotive from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from New England to California.”

It was a highly combative labor movement, and that combativity reached its height in the Great Rail Strike of 1877. The crushing of that strike coincided with the final undoing of Reconstruction. Some of the federal troops removed from the South were sent against the rail workers, an early example of how labor rights and black rights are intertwined. The growth of labor militancy in the U.S. and internationally helped persuade Northern capitalists that their class interests, which had led them into the Civil War to destroy the Southern slave system, now compelled opposition to the demands of the black freedmen, as well as to the struggles of the working class.

Despite the tenacious struggles of a few courageous white Radical Republicans like Sumner and his House colleague Thaddeus Stevens, as well as black leaders like Douglass, Reconstruction was defeated. The withdrawal of the last Union troops with the Compromise of 1877 made clear that Northern capital was interested in consolidating the economic advantages of its victory over the Confederacy, not in black rights. Left defenseless before their former owners, black people were driven out of government and off their land as Reconstruction regimes were smashed by naked racist terror.

A number of Supreme Court decisions, taken together, legally codified the end of Reconstruction. They also demonstrated that the courts are part of the bourgeois state machine, whose purpose is to defend capitalist class rule against the exploited and oppressed, regardless of which bourgeois party holds power. The core of the state consists of the police, army and prisons, as well as the courts. In 1883, the Supreme Court struck down the 1875 Civil Rights Act as unconstitutional. That Act, passed in honor of Sumner the year after his death, was a watered-down version of a bill he had proposed to promote integration. In 1896, the Court affirmed segregation as the law of the land in the Plessy decision. Homer Plessy, a man of mixed-race ancestry, sued in Louisiana after he was arrested for trying to sit in the “white section” of a train. The Court declared that if black people regard separate facilities as racial discrimination, it’s because they choose to interpret them as such, i.e., it’s all in their heads.

Arguing that segregation violates no part of the Constitution or its amendments, the Plessy ruling allowed separate treatment by race so long as it was supposedly equal. In Brown v. Board of Education: Caste, Culture, and the Constitution (2003), authors Robert Cottrol, Raymond Diamond and Leland Ware note: “At its zenith this system of segregation would turn Negroes into a group of American untouchables, ritually separated from the dominant white population in almost every observable facet of daily existence.” Laws were put into effect throughout the South mandating separate seating on buses, separate water fountains, separate bathrooms, separate schools, separate Bibles to swear on in court. Laws echoing those that existed in the time of slavery were passed that forbade white teachers from teaching black children.

It is out of the ashes of the defeat of Reconstruction that Booker T. Washington arose as the voice of accommodation to Jim Crow segregation. Washington disparaged Reconstruction and blamed black people for their own oppression, deeming them “unfit” for “high-minded” professions. In periods of defeat, like now, echoes are heard of Washington’s gospel of self-help, appealing to black youth to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps—in other words, to accept the racist status quo and look to the white rulers for patronage.

Heroic struggles erupted in the 1950s and ’60s that aimed to end the formal legal inequalities imposed on black people. Brown v. Board of Education struck down the doctrine of “separate but equal” for schools. But there was immediate and often violent resistance to desegregation, and foot-dragging by the federal government. In Prince Edward County, Virginia, starting in 1959 all public schools were shut down for five years to prevent integration. White kids got vouchers paid for by public funds to attend private schools; the black kids got nothing.

Fundamentally, the civil rights movement did not remedy the systemic racial oppression at the core of U.S. capitalism. Its liberal leadership, exemplified by Martin Luther King Jr., sought legal reforms through pressuring the capitalist Democrats and courts, the same forces maintaining de facto segregation outside the South. In the North, there were no laws forbidding black people to eat at the same lunch counters as whites; but the unwritten laws of American capitalist exploitation kept black people a “last hired, first fired,” doubly oppressed race-color caste. In 1965, the great writer James Baldwin remarked: “De facto segregation means Negroes are segregated, but nobody did it.”

In 1954, addressing how the Brown decision applied to segregation in New York City, the school superintendent insisted, “We have natural segregation here—it’s accidental.” Today, we hear that a lot, too. School officials in the North argued against using the word “segregation” on the grounds that segregation is deliberate—“racial imbalance” was the preferred term. The same thing is heard today, along with “lack of diversity.” While there was some struggle for school desegregation in the mid to late 1950s, it was in the early 1960s that larger struggles broke out.

Democrats and Social Democrats

In Chicago, segregation of housing and schools was openly enforced by the Democratic Party machine of Richard J. Daley. When the school superintendent, Benjamin Willis, was pressured to address overcrowding at black schools, he ordered 100 mobile classrooms rather than busing black kids to white schools. There was a boycott by over 222,000 students in 1963 against the segregation embodied in these “Willis wagons.” The Chicago Tribune called the boycott and other protest a “reign of chaos” and denounced the organizers as “reckless” for pulling kids out of school. That might sound familiar: the current “progressive” Democratic mayor, Lori Lightfoot, has lobbed similar vitriol at teachers who are now on strike. Daley and the Chicago Democrats viciously resisted any attempt at integration and made sure that schools and housing would stay segregated, as they still are.

In NYC, the struggle for integration reached a fever pitch in the early 1960s amid tumultuous struggles for decent housing and jobs and against rampant cop terror. In 1964, massive school boycotts by black and Puerto Rican parents and students were among the country’s largest civil rights demonstrations on record. The first boycott was led by liberal Brooklyn minister Milton Galamison and Bayard Rustin, today an icon of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), who was already an expert in selling out struggles on behalf of the Democratic Party, which he wanted to “realign.” Some 460,000 students didn’t go to school. There was a racist backlash, with 10,000 white mothers, organized as “parents and taxpayers,” marching across the Brooklyn Bridge to denounce “busing.”

A second boycott was called, but this time Rustin wouldn’t support it, labeling it too militant. Liberal white organizations saw the boycott as an inappropriate tactic; the New York Times declared it a “violent, illegal approach of adult-encouraged truancy!” Notably, Malcolm X supported the boycott, observing: “You don’t have to go to Mississippi to find a segregated school system, we have it right here in New York City.”

White Democratic Party politicians and black Democrats in the civil rights movement abandoned the battle. The NYC teachers union, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), was led by Albert Shanker, an anti-Communist “democratic socialist” who ran the UFT like a business. He refused to have the union endorse the 1964 school boycott for integration.

The Spartacist League intervened into the boycott. When the struggle for black rights develops a mass character, it poses a direct threat to the capitalist system but cannot go forward without a revolutionary leadership. Our Spartacist article (No. 2, July-August 1964) stated that such a leadership would seek “to educate the black workers about the real nature of the Democratic Party of cold-war liberals, Southern racists, kept union leaders, and Uncle Toms in order to break up the system of two capitalist parties which perpetuates the status quo.”

This struggle was happening in the lead-up to the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964. Here we see the racist role of the Democrats in full effect. It was a Democratic Congressman from Brooklyn, Emanuel Celler, who enabled the incorporation of an amendment that the act could not be used to “overcome racial imbalance” in public schools. There was an anti-busing amendment as well, to stop “any official or court of the United States to issue any order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by requiring the transportation of pupils or students from one school to another…in order to achieve such racial balance.” So here you have the Democrats gutting the civil rights legislation they claimed to support in the abstract and upholding the segregation of Northern schools. This anti-busing amendment would be regularly cited in the Chicago Tribune to argue in defense of school segregation.

The civil rights movement mainly benefited a thin layer of middle-class black people, but it could not make a dent in the deep-seated oppression of the black ghetto masses. The formula of equal rights under the law provides no answer to the miserable conditions of black life entrenched in American capitalist society: joblessness, crumbling homes, overcrowded schools, racist cop terror. Fed up with these conditions, Harlem erupted in 1964 and Watts in 1965, as did ghettos across the country over the next three years. These upheavals were an expression of the bankruptcy of the liberal-led civil rights movement in the face of these social conditions.

There was a growth in black separatist sentiment, which did not and could not generate a program of struggle to get rid of racial oppression under capitalism. The black nationalists who raised “community control” made a virtue of the ingrained segregation that was seen as unchangeable. By the late 1960s, “community control” had become a major slogan used by the ruling class, mainly acting through the Democratic Party, to co-opt a layer of young black activists. Many of these activists, including those who voiced white-baiting separatist rhetoric, became overseers of the segregated black ghettos. The actual content of the “community control” slogan was an appeal for more black Democratic Party politicians, cops, judges and administrators. Since then, black mayors have been installed in one major city after another to help contain the discontent of the black masses, while presiding over cop terror and unleashing attacks on social programs and labor.

All these events are the background to understanding the 1968 New York City teachers strike. The administration of Mayor John V. Lindsay was trying to bust the public employee unions, which were quite combative in the mid 1960s. There was a transit strike in 1966, led by Mike Quill. On its eve, Quill famously ripped up an anti-strike court injunction. Republican governor Nelson Rockefeller announced that he was “determined that this should never happen again.” The Taylor Law banning public employee strikes was put in place in 1967. When sanitation workers struck in early 1968, Lindsay decided that the time had come to break the public-sector unions.

Teachers had gone on strike in 1967, defying the Taylor Law. A leaflet we put out on September 24 after that strike noted the “policy of ‘professionalism’ advocated by the UFT leadership has held the union largely aloof from many of the past struggles of the ghetto communities, widening the gap between teacher, student and parent. Such a situation [of UFT indifference combined with black nationalist calls for ‘keeping the schools open’] provides a ready excuse for the development of racist attitudes.”

The spark for the 1968 strike came when the newly appointed black superintendent of Brooklyn’s Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district fired union teachers in order to replace them with non-union ones. Lindsay and Rockefeller, in cahoots with the Ford Foundation, pulled out all the stops to bust the union by mobilizing black people and Latinos in the ghettos and barrios against the strike, using the demagogic call for “community control” of the schools. While politically denouncing Shanker, we stood with the union, which was at that time disproportionately Jewish, in its fight for survival. In our leaflet “New York City School Strike: Beware Liberal Union Busters!” (13 November 1968), we sought to link the struggles of the union movement to those of New York’s black and Puerto Rican working people. Most of the reformist left came out in support of outright strikebreaking, siding with the “community control” crowd.

A few years later, there was a teachers strike in Newark, New Jersey, that played out differently. In 1971, black Democratic mayor Kenneth Gibson attacked the teachers union. However, because the union had an integrated membership and a black woman president, the ensuing teachers strike had substantial support from the city’s black population. The Newark teachers strike exposed the anti-union purpose behind the rhetoric of “community control” that had been wielded three years earlier in an attempt to break the NYC teachers union.

Racist Mobs and Liberals Defeat Busing

By the early to mid 1970s, the fight for school busing had become the front line in the fight for integration. The battle in Boston, a quintessential Democratic Party stronghold, took place almost 20 years after Brown and after every conceivable legal and political obstacle had been thrown up against integrating its schools. In 1974, a landmark Supreme Court decision prohibited busing black schoolchildren from Detroit to the suburbs, where the white schools were. This ruling set a precedent, including in Boston. The busing of black students there was purposely limited to neighborhoods like South Boston, known as Southie, which at the time was one of the poorest white areas outside of Appalachia. The aim was to pit poor and working-class whites against blacks. Again, demagogic politicians inflamed racist sentiments in these white ethnic enclaves under the watchwords of defend “neighborhood schools” and “stop forced busing.”

The Spartacist League intervened in Boston with a class-struggle program, calling to defend school busing as a minimal application of the elementary democratic right of black people to equality. We called to extend busing to the wealthier suburbs, so that poor kids, black and white, could have access to quality education. We called for quality, racially integrated housing and free universal higher education. While the NAACP and such craven reformists as the Socialist Workers Party called for federal troops to Boston, we fought for labor-black defense to stop racist mob attacks and protect black schoolchildren. We knew the defeat of busing in Boston would set the stage for further attacks against black people and for rolling back social gains more broadly, which it did.

All the metropolitan areas in the country with the most integrated schools had mandatory city-suburban busing plans. Most of these plans had been reversed or stopped by the 1990s. In 2007, the Supreme Court threw out school desegregation plans in Seattle and Louisville, enabling the overturn of others that remained across the country and eviscerating the Brown decision.

While busing was an inadequate solution to school segregation, it did not “fail” but was killed by an alliance of liberals in Congress and howling mobs of racists in the streets. The reformist left played its part in this defeat by channeling the fight to defend busing into faith in the Democrats and appeals for federal intervention.

A few months ago, an early Democratic Party presidential debate included the spectacle of Kamala Harris, former California attorney general, going after Joe Biden for opposing busing for black schoolchildren. Of course, Biden supported racist anti-busing measures as a Senator from Delaware. But this criticism is pure hypocrisy coming from Harris. For one, the role played by Biden in killing busing was not his alone, but that of the Democratic Party as a whole. And while a younger Harris personally benefited from the busing program in Berkeley, California, she went on to bus thousands of black and Latino youth, only not to better schools but to prison hellholes.

A number of petty-bourgeois liberal writers have powerfully documented the segregated and horrible conditions of the majority of public schools in this country. But they all propose the same dead-end answer of a better capitalist government to change things, while putting the fundamental blame on racist backwardness among whites.

This is a deeply and viciously racist country. But backward consciousness is not the source of racial oppression, although it is part of sustaining the oppression and degradation of black people, Latinos and other minorities. Racial oppression fundamentally stems from the American capitalist system and division of the working class along racial lines. As veteran American Trotskyist Richard Fraser put it:

“Karl Marx proved conclusively, however, that it was not greed but property relations which make it possible for exploitation to exist. When applied to the Negro question, the theory of morality means that the root of the problem of discrimination and white supremacy is prejudice. This is the reigning theory of American liberalism and is the means by which the capitalists throw the responsibility for the Jim Crow system upon the population as a whole. If people weren’t prejudiced there would be no Negro problem. This contention is fundamentally false.”

— “The Negro Struggle and the Proletarian Revolution” (1953), printed in “In Memoriam— Richard S. Fraser,” Prometheus Research Series No. 3, August 1990

The capitalist rulers have profited immensely by sowing racial divisions, pitting white workers against blacks, Asians against blacks and Latinos, blacks against immigrants and so on. They want to mask the fact that the class division between the workers and the capitalists is the primary dividing line in this society. Truth is, racial oppression serves to deepen the exploitation of all workers. The horrific conditions of life that black and immigrant workers have long endured are increasingly faced by the working class as a whole.

Funding for education and other social services is always rationed in a way that purposely fans racial and ethnic tensions. De Blasio’s pseudo-attempt to get rid of the racist, elite NYC high school exam was fiercely opposed by some Asian parents, who bought into the bourgeoisie’s lie that “merit” is what gets one to the top. To this end, the rulers have long invoked the myth of the Asian “model minority” as yet another way to blame black people for their own oppression. Such pernicious stereotypes also disappear national and class differences among Asians. In NYC alone, some quarter-million Asians live in poverty. Asians are also a component part of labor in the city.

Asians, as well as Latinos and other predominantly non-white minorities, suffer oppression in capitalist America. However, as an intermediate layer, they navigate a society where the main racial divide is between black and white, and every institution is permeated by anti-black racism. Many Latino students in the U.S. attend deeply segregated and impoverished schools. In California, Latinos attend schools that are 84 percent non-white. There is also a whole history of segregation of Latinos on the basis of anti-Spanish discrimination, including “English only” schools.

In 1970, a federal district court ruled that the Brown decision applied to segregation of Mexican students in Texas. In response, Houston school officials classified Mexican students as “white” in order to place them in black schools and then declared those schools “integrated,” while leaving white schools untouched. The rights of workers, Latinos and Asians, black people and immigrants will either go forward together or fall back separately. That’s why we emphasize the fight for bilingual education as part of the struggle for free, quality, integrated education for all. Bilingual education, which is vital for all Spanish-speaking and immigrant children, would also benefit native English speakers.

For Free, Quality, Integrated Public Education for All!

Today, the blame for the lack of learning and for low test scores is cynically put on teachers and their unions. But over the last four decades, public education has come under sustained bipartisan assault, from extreme cutbacks to widespread school closures. The Obama administration led the pack in launching sweeping attacks on the public schools and the teachers unions packaged as education “reform,” which included a major expansion of the privately run charter industry.

Among the advocates of this “reform” are some of America’s biggest billionaires and venture capitalists, like Bill Gates and Sam Walton. Cornell University professor Noliwe Rooks, in her book Cutting School (2017), usefully details how increased privatization of the public schools is a way to slash the cost of educating poor and minority youth and at the same time enables individual capitalists to make lots of money. She writes: “Charter schools,…vouchers, virtual schools, and an alternatively certified, non-unionized teaching force represent the bulk of the contemporary solutions offered as cures for what ails communities that are upward of 80 percent Black and Latino.”

Out of desperation over the awful state of inner-city public schools, many black and Latino parents have been manipulated into thinking that charter schools are some kind of answer. In fact, the overwhelmingly non-union charters are even more segregated than the public schools and are notorious for vicious discipline and excluding non-English speakers and disabled students. We call for class struggle to destroy the charter industry through bringing its teachers and staff into the public schools and the unions. An important step in this direction would be for labor to organize the existing charters, as has already happened in some cases. Teachers at recently unionized charters in Chicago have engaged in strike action; unity in struggle of Chicago public school and charter teachers would give a big boost to further organizing drives.

There has been a series of teachers strikes across the country, beginning in West Virginia a year and a half ago up through Chicago today. These walkouts over better pay and conditions found wide support as well as some expressions of solidarity from other unions. But the potential impact of these battles has largely been wasted by the trade-union officialdom that ties the unions to the same Democratic Party that has been attacking them and devastating public education.

An article on the Chicago teachers strike in the DSA-sponsored Jacobin was titled “It’s Chicago Educators Versus the Ruling Class” (23 October). However, it declares, “Following Sanders’s lead, Harris, Warren, and Biden, have expressed support for union demands, exposing [Chicago mayor Lori] Lightfoot’s pro-big business economic program”—as though these other Democrats don’t have a pro-big business program. They all are capitalist politicians upholding viciously racist U.S. imperialism.

Every child across the country, whatever their background, deserves to attend a school with the same level of resources now allocated to the elite NYC high schools. The same filthy rich ruling class attacking public education and teachers unions from L.A. to Chicago to NYC has been waging a broader one-sided class war against working people in this country. From auto workers in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and Flint, Michigan, to transit and sanitation workers in NYC and Chicago, the multiracial working class has every interest in fighting for free, quality, integrated public education for all, up to and including the universities!

But it will take a leap in consciousness and organization for the proletariat to bring its power to bear in this fight, which must be linked to the struggle for its own freedom from capitalist wage slavery. Key to this task is building a revolutionary, internationalist workers party that will politically combat those like the DSA and the reformist Socialist Alternative that push support to the same old racist capitalist Democratic Party of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sanders, as well as Nancy Pelosi and Biden. This support has only led to defeats for the oppressed and blocks the road to liberation.

Our model is Lenin and Trotsky’s Bolshevik Party, which led the working class to power in the Russian Revolution of October 1917. That revolution was a beacon for the workers and oppressed around the world and sent shivers down the U.S. bourgeoisie’s spine. Tsarist Russia had been, in Lenin’s words, a “prison house of peoples” of many oppressed nations and national minorities. By building a revolutionary party based on the social power of the workers, with a clear political program opposing capitalist exploitation, national oppression and all forms of Great Russian chauvinism, the Bolsheviks were able to shatter the old order. They sought to truly provide education to the masses and to do away with the bourgeois distinction between mental and manual labor.

Our task in the U.S. is to build a party like the Bolsheviks, with a heavily black and Latino leadership, that mobilizes all workers to fight black oppression. Communist leadership and interracial class struggle can break down racial and ethnic divisions within the working class. A revolutionary workers party, acting as a tribune of all the oppressed, can bring together the power of labor with the anger of the ghettos and barrios in order to smash this entire system of racist capitalist oppression and bring about workers rule. A socialist revolution will finish the unfinished tasks of the Civil War, achieving freedom and equality for black people in this country. It will take nothing less to realize such a basic demand as, “All children, without discrimination, will sit together”!