Workers Vanguard No. 938

|

5 June 2009

|

| |

The Civil War: The Second American Revolution

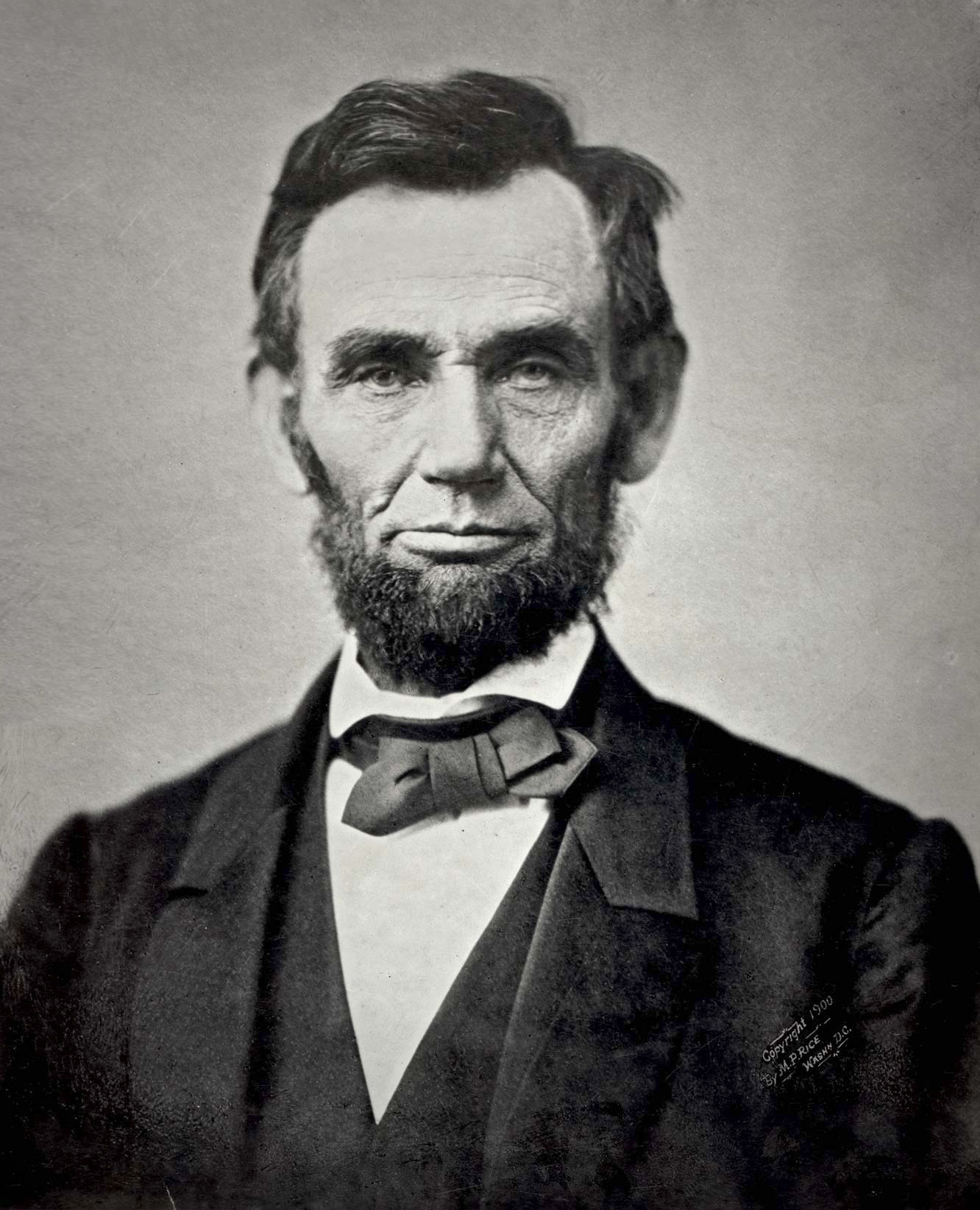

Honor Abraham Lincoln!

By Bert Mason

The following was written as a contribution for a Spartacist League internal educational series.

February 12 marked the bicentennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth. Since the days of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the founders of scientific socialism, revolutionaries have held Lincoln in high esteem. His world-historic achievement—the single most important event in American history

—was to lead the North in a horrendously bloody civil war that smashed the Southern Confederacy and abolished slavery in the United States. In “Comments on the North American Events” (7 October 1862), Marx wrote with characteristic eloquence:

“Lincoln is a sui generis figure in the annals of history. He has no initiative, no idealistic impetus, no cothurnus [dignified, somewhat stilted style of ancient tragedy], no historical trappings. He gives his most important actions always the most commonplace form. Other people claim to be ‘fighting for an idea,’ when it is for them a matter of square feet of land. Lincoln, even when he is motivated by an idea, talks about ‘square feet.’ He sings the bravura aria of his part hesitatively, reluctantly and unwillingly, as though apologising for being compelled by circumstances ‘to act the lion.’…

“Lincoln is not the product of a popular revolution. This plebeian, who worked his way up from stone-breaker to Senator in Illinois, without intellectual brilliance, without a particularly outstanding character, without exceptional importance—an average person of good will, was placed at the top by the interplay of the forces of universal suffrage unaware of the great issues at stake. The new world has never achieved a greater triumph than by this demonstration that, given its political and social organisation, ordinary people of good will can accomplish feats which only heroes could accomplish in the old world!”

Many opponents of revolutionary Marxism, from black nationalists to reformist leftists, have made a virtual cottage industry out of the slander that “Honest Abe” was a racist or even a white-supremacist. The reformist who impugns Lincoln for his bourgeois conceptions, which in fact reflected his time, place and position, does not hesitate for a moment to ally with unctuous “progressives” today who praise “diversity” while fighting tooth and nail to maintain the racial oppression and anti-immigrant chauvinism that are endemic to this most brutal of imperialist countries.

Take the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). In Cold Truth, Liberating Truth: How This System Has Always Oppressed Black People, And How All Oppression Can Finally Be Ended, a pamphlet originally published in 1989 and reprinted in Revolution (17 February 2008), the RCP writes:

“It is a lie that ‘Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves’ because he was morally outraged over slavery. Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation freeing the slaves (and not all the slaves at first, but only those in the states that had joined the southern Confederacy) because he saw that it would be impossible to win the Civil War against that southern Confederacy without freeing these slaves and allowing them to fight in the Union army.

“Lincoln spoke and acted for the bourgeoisie—the factory-owners, railroad-owners, and other capitalists centered in the North—and he conducted the war in their interests” (emphasis in original).

Aside from the scurrilous suggestion that Lincoln was not an opponent of slavery who abhorred that “peculiar institution,” the RCP rejects Marxist materialism in favor of liberal moralizing, denying that against the reactionary class of slaveholders and the antiquated slave system, the Northern capitalists represented a revolutionary class whose victory was in the interests of historical progress. Presenting the goals of the North and South as equally rapacious, the RCP neither sides with the North nor characterizes its victory as the consummation of a social revolution.

Indeed, the Civil War—the Second American Revolution—was the last of the great bourgeois revolutions, which began with the English Civil War of the 17th century and found their culmination in the French Revolution of the 18th. For the RCP, however, there is no contradiction whatsoever in condemning Lincoln as a representative of the 19th-century American bourgeoisie while doing everything in its power to embrace bourgeois liberalism today—from its antiwar coalitions with capitalist spokesmen to its implicit support for the Democratic Party and Barack Obama in the name of “drive out the Bush regime.”

Abraham Lincoln: Bourgeois Revolutionary

In the preface to his 1859 book, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Karl Marx wrote that in studying the transformation of the whole immense superstructure that arises from revolutionary changes in the economic foundation:

“It is always necessary to distinguish between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, artistic or philosophic—in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out. Just as one does not judge an individual by what he thinks about himself, so one cannot judge such a period of transformation by its consciousness, but, on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained from the contradictions of material life, from the conflict existing between the social forces of production and the relations of production. No social formation is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.”

The American Civil War was a bourgeois revolution, and Lincoln was both bourgeois and revolutionary at the same time—with all the contradictions this implies. Because the task of the Second American Revolution was to eradicate an antiquated social system based on chattel slavery and erect in its place the dominion of industrial capitalism based on wage labor from one end of the North American landmass to the other, it could not eradicate every form of class and social oppression—the hallmark of all propertied classes throughout the history of class society. As materialists, Marxists do not judge historical figures primarily based on the ideas in their heads but on how well they fulfilled the tasks of their epoch. While Lincoln had bourgeois conceptions—how could it be otherwise!—he was uniquely qualified to carry out the task before him, and in the last analysis he rose to the occasion as no other. That is the essence of his historical greatness.

While bestowing begrudging praise on Lincoln’s achievements with the left hand, the leftist critic often takes it back with the right. Lincoln, the critic will admit, opposed slavery; he came to see that a hard war was necessary and prepared to issue his Emancipation Proclamation. However, the critic is more concerned with Lincoln’s attitudes than his deeds: Lincoln was not John Brown, he was not Frederick Douglass, he was not Marx and Engels, he was not even as left-wing as his Treasury secretary Salmon P. Chase. For example, while Lincoln agreed with John Brown in thinking slavery wrong, he could not excuse Brown’s violence, bloodshed and “acts of treason” in attempting to seize the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry to spark a slave rebellion on the eve of the Civil War. Finally, the critic will argue, while Marx and Engels from 3,000 miles away knew that the American Civil War was about slavery, Lincoln and the Republicans sought to ignore the root of the problem and wage the conflict on constitutional grounds to save the Union. Such facts are indisputable, but they must be seen in their historical context.

In his Abraham Lincoln (2009), James M. McPherson remarks:

“Only after years of studying the powerful crosscurrents of political and military pressures on Lincoln did I come to appreciate the skill with which he steered between the numerous shoals of conservatism and radicalism, free states and slave states, abolitionists, Republicans, Democrats, and border-state Unionists to maintain a steady course that brought the nation to victory—and the abolition of slavery—in the end. If he had moved decisively against slavery in the war’s first year, as radicals pressed him to do, he might well have fractured his war coalition, driven border-state Unionists over to the Confederacy, lost the war, and witnessed the survival of slavery for at least another generation.”

Facing innumerable pressures when the war broke out in April 1861, Lincoln grappled with how to respond to them. But the pressures—as intense as they were—were not merely strategic in nature. As the president of a constitutional republic, Lincoln believed that it was his duty to uphold the Constitution and the rule of law. While he detested slavery, he believed it was not his right to abolish it. That ideology flowed from the whole bourgeois constitutional framework of the United States.

In the first year of the war, Lincoln pursued a policy of conciliating the four border slave states—Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri—in an effort to retain their loyalty to the Union. Marx and Engels criticized this policy because it weakened the Union’s war effort and emboldened the slaveholders. However, did this policy stem from disdain for the enslaved black masses or from a desire on Lincoln’s part to let bygones be bygones—i.e., coexist with the slave South? No. It flowed from the whole previous history of the United States. In 1776, 1800 and even as late as 1820, the North and South had similar values and institutions. With the Industrial Revolution, however, the North surged ahead in virtually every area—railroads, canals, literacy, inventions—while the South stagnated. Yet the two regions remained part of the same nation, setting the stage for compromise after compromise. For a whole historical period, Lincoln was hardly alone in seeking détente. In 1848, even the more left-wing Salmon Chase rejected the view espoused by radicals in his Liberty Party that the Constitution empowered the government to abolish slavery in the states, preferring a bloc with antislavery Whigs and Democrats that would agitate merely for keeping slavery out of the territories.

While he conciliated the border states for a time, Lincoln stood firm against secession, countering his cabinet members’ willingness to compromise in the face of the Confederacy’s belligerence. After his fateful election in 1860, which set the stage for the secession of the Southern states and the Civil War, Lincoln reined in his future secretary of state William H. Seward for advocating support to the Crittenden Compromise, an attempt to allow slavery to flourish anywhere south of 36°30'. Then Lincoln rejected Seward’s proposal to abandon Fort Sumter in the Charleston, South Carolina, harbor. Had it not been for Lincoln’s relentless efforts to goad his officers to fight and his stubborn support for Ulysses S. Grant in the face of substantial Northern opposition, the North might not have vanquished the slavocracy in that time and place. Lincoln’s resoluteness, his iron determination to achieve victory and his refusal to stand down to the Confederacy are hallmarks of his revolutionary role and enduring testaments to his greatness.

Borrowing from today’s terminology, one could argue that Lincoln began as a reformist, believing that the reactionary social system in the South could be pressured into change and that the institution of slavery would eventually wither on the vine. But he underwent a radical shift when bloody experience in the crucible of war—combined with the mass flight of the slaves to the Union lines—taught him that the nation could be preserved only by means of social revolution. In contrast to this remarkable personal transformation, the Great French Revolution required a series of tumultuous stages to reach its revolutionary climax, a protracted process that was marked by the domination of different and antagonistic groupings—from the Girondins to the Montagnards to the Committee of Public Safety. The Mensheviks were also reformists, but they didn’t become revolutionaries but counterrevolutionaries.

Was Lincoln a Racist?

Although it is beyond dispute that Lincoln occasionally appealed to racist consciousness and expressed racist opinions, the record is not as cut-and-dried as the typical liberal moralist or his leftist cousin will assert. Before a proslavery crowd in Charleston, Illinois, during the fourth debate with Stephen A. Douglas on 18 September 1858, Lincoln declared:

“I will say, then, that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races; that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say, in addition to this, that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And in as much as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I, as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

Yet two months earlier in Chicago, Lincoln had insisted, “Let us discard all this quibbling about this man and the other man, this race and that race and the other race being inferior, and therefore they must be placed in an inferior position; discarding our standard that we have left us. Let us discard all these things, and unite as one people throughout this land, until we shall once more stand up declaring that all men are created equal.”

However, more important than these words were Lincoln’s actions in defense of the slaves, the freedmen and the black troops in the Union Army. For example, in the autumn of 1864, pressure mounted for Lincoln to consummate a prisoner exchange that would exclude black soldiers. Some Republican leaders warned that Union men “will work and vote against the President, because they think sympathy with a few negroes, also captured, is the cause of a refusal” to exchange prisoners. Ignoring these threats, Lincoln’s agent in the exchange negotiations asserted, “The wrongs, indignities, and privations suffered by our soldiers would move me to consent to anything to procure their exchange, except to barter away the honor and the faith of the Government of the United States, which has been so solemnly pledged to the colored soldiers in its ranks” (James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom [1988]).

That’s not all. Confronting growing defeatist sentiment in the North, the grim prospect of defeat in the impending 1864 presidential elections and a cacophony of demands to abandon the Emancipation Proclamation from Democrats and even staunch Republicans, Lincoln stood firm. In response to fulminations such as “Tens of thousands of white men must yet bite the dust to allay the negro mania of the President,” Lincoln responded, “If they [the black soldiers] stake their lives for us they must be prompted by the strongest motive—even the promise of freedom. And the promise being made, must be kept.” Emphasizing the point, he maintained, “There have been men who have proposed to me to return to slavery the black warriors of Port Hudson & Olustee to their masters to conciliate the South. I should be damned in time & in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies, come what will.”

In the last months of the war, the emancipation of the slaves began to raise broader political and economic questions. When reports filtered northward of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s indifference toward the thousands of freedmen that had attached themselves to his army, Lincoln’s war secretary Edwin Stanton traveled to Savannah, Georgia, in January 1865 to talk with Sherman and consult with black leaders. As a result of Stanton’s visit, Sherman issued “Special Field Orders, No. 15,” which granted the freed slaves rich plantation land belonging to former slaveholders.

Indignantly protesting that Lincoln valued the restoration of the Union over the emancipation of the slaves, the RCP cites his famous letter to Horace Greeley of 22 August 1862, which declared: “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” The RCP neglects to add that a month later, on September 22, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Commenting on this momentous event, Marx called Lincoln’s manifesto abolishing slavery “the most important document in American history since the establishment of the Union, tantamount to the tearing up of the old American Constitution.”

What was more important for Lincoln’s cause, Union or emancipation? The very question betrays a subjective idealist approach that ignores the objective reality of the time. The two tasks had become inextricably intertwined in the reality of a war that pitted a modern industrial capitalist mode of production in the North against an archaic agrarian slave system in the South. Restoration of the Union required emancipation, and emancipation required a Union victory. For embodying and melding those two great tasks, Lincoln will forever occupy an honored place in history.

Much Ado About Colonization

An oft-repeated theme among Lincoln’s detractors is that the 16th president—a racist to his bones, they assert—was dedicated above all else to deporting the freed black slaves to distant shores. The most caustic purveyor of this timeworn slander is Lerone Bennett Jr., executive editor emeritus of Ebony and the author of Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream (2000). Bennett shrieks that “Abraham Lincoln’s deepest desire was to deport all black people and create an all-white nation. It’s—sounds like a wild idea now and it is a wild idea, but from about 1852 until his death, he worked feverishly to try to create deportation plans, colonization plans to send black people either to Africa or to...South America, or to the islands of the sea” (interview with Brian Lamb, 10 September 2000, www.booknotes.org/transcript/?programID=1581).

Lincoln did not invent the idea of colonization. Schemes to remove black people from the United States went back to the American Colonization Society, which was founded in 1816. Very much a product of his times, Lincoln was long a supporter of colonization because he believed that the ideal of racial harmony in America was impossible. Although reprehensible and misguided, Lincoln’s colonization schemes were motivated not by racist antipathy toward black people but by his perceptions of enduring white racism in America. In the course of meeting with black leaders at the White House on 14 July 1862, Lincoln declared:

“You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race suffer very greatly, many of them by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word, we suffer on each side. If this is admitted, it affords a reason at least why we should be separated….

“Your race are suffering, in my judgment, the greatest wrong inflicted on any people. But even when you cease to be slaves, you are yet far removed from being placed on an equality with the white race. You are cut off from many of the advantages which the other race enjoy. The aspiration of men is to enjoy equality with the best, when free; but on this broad continent not a single man of your race is made the equal of a single man of ours. Go where you are treated the best, and the ban is still upon you.”

— cited in “Report on Colonization and Emigration, Made to the Secretary of the Interior, by the Agent of Emigration” (1862)

It is therefore not surprising that Lincoln advocated colonization most strenuously at the very moment that he was preparing his Provisional Emancipation Proclamation following the watershed Union victory at Antietam, which Marx said “decided the fate of the American Civil War.” With his colonization proposals, Lincoln sought to sweeten what many whites considered the bitter pill of black emancipation.

However indefensible the idea of colonization was, Lincoln insisted that it must be voluntary. Even then, blacks overwhelmingly rejected colonization as both racist and impractical, holding anticolonization meetings in Chicago and Springfield to protest it. Indeed, Frederick Douglass declared in September 1862: “Mr. Lincoln assumes the language and arguments of an itinerant Colonization lecturer, showing all his inconsistencies, his pride of race and blood, his contempt for Negroes and his canting hypocrisy.” One of the administration’s two concrete moves to implement colonization, the Île à Vache fiasco, led to the deaths of dozens of freed blacks. However, when Lincoln learned of the disaster, he did the honorable thing and ordered the Navy to return the survivors to the United States.

Besides free blacks and Radical Abolitionists, many other contemporaries of Lincoln were incensed at his colonization efforts. Publications like Harper’s Weekly considered the proposal to resettle millions of people to distant shores insane. In Eric Foner’s words, “For what idea was more utopian and impractical than this fantastic scheme?” (“Lincoln and Colonization,” in Our Lincoln: New Perspectives on Lincoln and His World, ed., Eric Foner [2008]).

By the waning days of the war, Lincoln’s utterances on colonization—if not his attitude—had evolved. In a diary entry dated 1 July 1864, Lincoln’s secretary John Hay remarked, “I am glad that the President has sloughed off the idea of colonization.” But much more to the point than attempts to decipher Lincoln’s attitudes is the indisputable fact that Lincoln’s policies on the ground were progressively rendering his colonization schemes a dead letter. Foner writes that in 1863 and 1864, Lincoln began to consider the role that blacks would play in a post-slavery America. He showed particular interest in efforts that were under way to establish schools for blacks in the South Carolina Sea Islands and in how former slaves were being put to work on plantations in the Mississippi Valley. In August 1863, he instructed General Nathaniel P. Banks to establish a system in Louisiana during wartime Reconstruction in which “the two races could gradually live themselves out of their old relation to each other, and both come out better prepared for the new.”

Historian Richard N. Current wrote, “By the end of war, Lincoln had abandoned the idea of resettling free slaves outside the United States. He had come to accept the fact that Negroes, as a matter of justice as well as practicality, must be allowed to remain in the only homeland they knew, given education and opportunities for self-support, and started on the way to complete assimilation into American society” (cited at “Mr. Lincoln and Freedom,” www.mrlincolnandfreedom.org). Indeed, on 11 April 1865, following Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln gave a speech in which he declared that literate blacks and black Union Army veterans should have the right to vote in a reconstructed Union—an early step toward the 14th Amendment and citizenship for the freed slaves.

A dishonest charlatan that considers Lincoln no better than Hitler, Lerone Bennett brings the very concept of scholarship into disrepute. In disgust at Bennett’s diatribes, one critic, Edward Steers Jr., sarcastically titled his review, “Great Emancipator or Grand Wizard?” And McPherson wrote that while Lincoln “was not a radical abolitionist, he did consider slavery morally wrong, and seized the opportunity presented by the war to move against it. Bennett fails to appreciate the acuity and empathy that enabled Lincoln to transcend his prejudices and to preside over the greatest social revolution in American history, the liberation of four million slaves” (“Lincoln the Devil,” New York Times, 27 August 2000).

Honor Lincoln— Finish the Civil War!

At times, Frederick Douglass was highly critical of Lincoln’s moderation and his relegation of black people to the status of what he called “step-children.” But Douglass also saw another side of the 16th president. In his autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1882), the great abolitionist wrote of his meeting with Lincoln at the White House in 1864:

“The increasing opposition to the war, in the North, and the mad cry against it, because it was being made an abolition war, alarmed Mr. Lincoln, and made him apprehensive that a peace might be forced upon him which would leave still in slavery all who had not come within our lines. What he wanted was to make his proclamation as effective as possible in the event of such a peace.… What he said on this day showed a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I had ever seen before in anything spoken or written by him. I listened with the deepest interest and profoundest satisfaction, and, at his suggestion, agreed to undertake the organizing of a band of scouts, composed of colored men, whose business should be somewhat after the original plan of John Brown, to go into the rebel States, beyond the lines of our armies, and carry the news of emancipation, and urge the slaves to come within our boundaries.”

Rather than weigh the “good” Lincoln against the “bad” in search of the golden mean, Marxists must seek to understand that he was a bourgeois politician in a time of war and revolution—“a big, inconsistent, brave man,” in the words of W.E.B. Du Bois (cited in Henry Louis Gates Jr., “Was Lincoln a Racist?” The Root, available at www.theroot.com/views/was-lincoln-racist).

With the election of Barack Obama as America’s first black president, bourgeois media pundits are acting as if he is the reincarnation of Abraham Lincoln. Billboards show a huge portrait of Lincoln with Obama’s face superimposed on it. Obama takes the presidential oath on Lincoln’s Bible. Liberal students go a step further, preferring Obama over Lincoln because Lincoln, they assert, was a racist who would have disapproved of a black president. In fact, U.S. imperialism’s current Commander-in-Chief has as much in common with the bourgeois revolutionary Abraham Lincoln as British prime minister Gordon Brown has with the great English revolutionary Oliver Cromwell or French president Nicolas Sarkozy has with the French revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre.

In condemning Lincoln as a racist and besmirching his supreme role in the liquidation of slavery, fake leftists like the RCP surely must have a hard time with Marx’s November 1864 letter to Lincoln on behalf of the First International congratulating the American people for his re-election as president (see accompanying box). By declaring that the European workers saw the star-spangled banner as carrying the destiny of their class, was Marx forsaking the red flag of communism? Not at all. For Marx and the workers of the Old World, Lincoln’s re-election guaranteed the irreversibility of the Emancipation Proclamation; it meant that the Union Army—first and foremost its “black warriors”—did not fight in vain. And they understood that with the demise of the slave power, the unbridled growth of capitalism would lay the foundation for the growth of the American proletariat—capitalism’s future gravedigger.

At bottom, the impulse to denounce Lincoln and to minimize his monumental role in history denies that political people—even great ones—are constrained by objective reality. If only poor Lincoln had not lacked the necessary will to eradicate all forms of racial oppression! As Marx explained, “Mankind thus inevitably sets itself only such tasks as it is able to solve, since closer examination will always show that the problem itself arises only when the material conditions for its solution are already present or at least in the course of formation” (A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy [1859]). The elimination of racial oppression in all its forms was not possible in 1861 or 1865 because the objective means to accomplish it were not yet present—the unfettered growth of industrial capitalism in America and the development of the working class.

Lincoln accomplished the task placed before him by history: the abolition of slavery. He could do so despite, and because of, the conceptions in his head. The task of Trotskyists—revolutionary Marxists—is different. Our aim is proletarian revolution. Our perspective is revolutionary integrationism. While opposing every manifestation of racist oppression, we underline that liberating black people from racial oppression and poverty—conditions inherent to the U.S. capitalist system—can be achieved only by establishing an egalitarian socialist society. Building such a society requires the overthrow of the capitalist system by the working class and its allies. This is possible only by forging a revolutionary, internationalist working-class party that champions the rights of all the oppressed and declares war on all manifestations of social, class and sexual oppression. That task will be fulfilled by a third American revolution—a workers revolution.