On The 50th Anniversary Of The Mississippi Freedom Summer -All Honor To The Black Liberation Fighters -Terry Gross -NPR

50 Years Ago, Students Fought For Black Rights During 'Freedom Summer'

50 Years Ago, Students Fought For Black Rights During 'Freedom Summer'

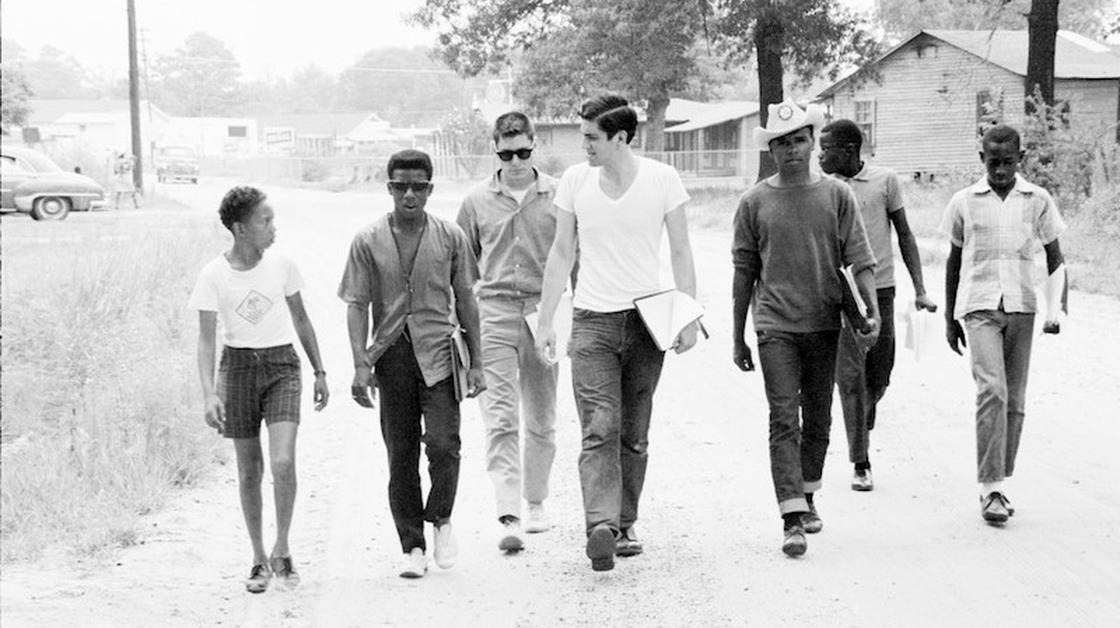

hide captionFreedom Summer volunteers and locals canvass in Mississippi in 1964 to get black people to the polls.

Freedom Summer volunteers and locals canvass in Mississippi in 1964 to get black people to the polls.

Courtesy of Ted Polumbaum/NewseumFreedom Summer was organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, which recruited 700 college students — mostly white students from the North — to travel to Mississippi and help African-Americans register to vote. The organizers, the students and the black people trying to register were all risking their lives, a measure of how pervasive racism was at the time.

A new documentary about the movement, called Freedom Summer, airs on PBS Tuesday.

hide captionA missing persons poster displays the photographs of civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner after they disappeared in Mississippi. It was later discovered that they were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan.

Just as Freedom Summer was beginning, two white participants, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, and one African-American organizer, James Chaney, disappeared. It was later discovered they were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan.

Charles Cobb, one of the movement's organizers featured in the film, was a field secretary for SNCC in Mississippi. He says he had been working there full-time for two to three years when the organization decided to bring attention to the state.

"We knew the people who would be coming would be mostly white and that the country would be concerned," Cobb says.

The murders affected the project, he says.

"As you might expect, it alarmed [the students'] parents," he says. "And the parents began calling the congressmen, and began calling — if they could — the White House, and saying, 'You better make sure that our kids get out of Mississippi alive.' "

Interview Highlights

On recruiting students from the NorthStanley Nelson: Very, very early it was decided [they would] bring down 700 to 1,000 students, and they went about recruiting in different ways, mainly ... from college campuses. So one person in the film, a woman, said she just saw a poster up at her college campus and went to a meeting and signed up.

One of the things that we show in the film, we found this great footage of them — SNCC and CORE [the Congress of Racial Equality] — doing interviews. People had to go through an interview process because [the organizers] really understood that this was going to be dangerous, and they had to get a core group of people to go down who also understood that this was going to be dangerous.

Charles Cobb: We could show people how best to try and protect yourself from actual physical [harm] — what to do if you're attacked by a mob, how to cover your body, how to protect somebody who you're with without engaging in fistfights or whipping out a pistol. ... We could show people how to do that. We had some experience in that because we all came out of the sit-in movement and were used to being surrounded by mobs of hostile whites.

On the murder of volunteers the day before the group was scheduled to arrive in Mississippi

Nelson: Mickey Schwerner had been in Mississippi for months before as an organizer; James Chaney was a local African-American, a Mississippian, who was also part of CORE and an organizer. They had gone up to Oxford, Ohio, to the training and there [they] met Andrew Goodman. A church was bombed in Mississippi and ... James Chaney and Mickey Schwerner decided to go down early and to see what happened, because that was in the area they were working. Andrew Goodman went with them. ...

This was, I think, a day before the rest of the group was going to go down to Mississippi. This was really even before the actual Freedom Summer had started. They went down and the day after ... they disappeared.

Cobb: It was an example of what we had really been talking to volunteers about before the three were missing, that you are going in to a murderously violent state and you have to understand that the danger affects you every day, all day long. The missing workers drove that point home because we were quite frank telling the volunteers, "We think they are dead." ...

hide captionFannie Lou Hamer was an activist who spoke out for black rights during Freedom Summer.

Fannie Lou Hamer was an activist who spoke out for black rights during Freedom Summer.

Courtesy of Ken Thompson/General Board of Global Ministries of The United Methodist ChurchNelson: When the white community heard that this Freedom Summer was going to happen, I think, in some ways, they overreacted completely. In Jackson, Miss., the city bought a tank that they armed; they increased the jail capacity. They were really ready for riots and they wanted to portray it that way. ...

The Ku Klux Klan, which had kind of been silent for a long time in Mississippi, [started] to rise again.

On the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

Nelson: 1964 was a presidential election year and Lyndon Johnson would be nominated for the presidency in Atlantic City. The idea of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was to take an alternate delegation to the convention in Atlantic City and try to obtain the right to be seated as opposed to the regular delegation from Mississippi.

The regular delegation from Mississippi was all-white. There was no way an African-American person could become part of that delegation, and that was against the rules of the Democratic National Convention — so the idea was, "We will take our own delegation, which is integrated, and we will take that and get a hearing at the Democratic National Convention and be seated as the delegation from Mississippi." ...

[The MFDP] got what it wanted. ... It got its hearing at the convention. And it had an incredible lineup, which was televised from the convention. Martin Luther King [Jr.] spoke in favor of the [MFDP]... and they really won the day.

On the gains of the Freedom Summer movement

Cobb: One important gain was [that] the challenge to the Mississippi Democratic Freedom Party changed the National Democratic Party. It's out of this challenge that you get what are now known as the [former Sen. George] "McGovern rules," which expanded the participation of women and minorities in the Democratic Party.

I think attitudes were changed in Mississippi. People saw that it was possible, in a wider sense, to struggle against white supremacy — and it changed the attitudes of those students who participated in that. Mario Savio, who would shortly lead the free speech movement at Berkeley in California, was a volunteer in Mississippi; so was [former Massachusetts Rep.] Barney Frank. I think it changed the attitude of these young people who came south.

No comments:

Post a Comment