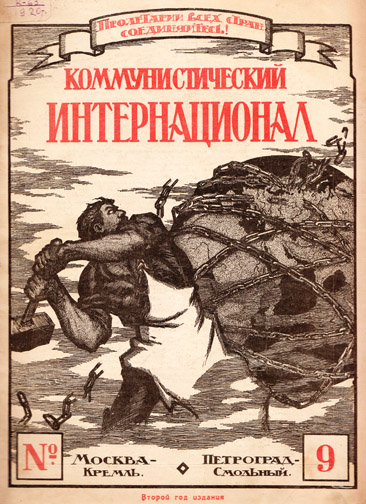

Honor The 90th Anniversary Of The Founding Of The Communist International (March, 1919)- Honor The Anniversary Of The Historic First World Congress Of The CI

Markin comment:

Some anniversaries, like those marking the publication of a book, play or poem, are worthy of remembrance every five, ten, or twenty-five years. Other more world historic events like the remembrance of the Paris Commune of 1871, the Bolshevik Russian Revolution of 1917, and, as here, the founding of the Communist International (also known as the Third International, Comintern, and CI) in 1919 are worthy of yearly attention. Why is that so in the case of the long departed (1943, by Stalin fiat) and, at the end unlamented, Comintern? That is what this year’s remembrance, through CI documentation and other commentary, will attempt to impart on those leftist militants who are serious about studying the lessons of our revolutionary, our communist revolutionary past.

No question that the old injunction of Marx and Engels as early as the Communist Manifesto that the workers of the world needed to unite would have been hollow, and reduced to hortatory holiday speechifying (there was enough of that, as it was) without an organization expression. And they, Marx and Engels, fitfully made their efforts with the all-encompassing pan-working class First International. Later the less all encompassing but still party of the whole class-oriented socialist Second International made important, if limited, contributions to fulfilling that slogan before the advent of world imperialism left its outlook wanting, very wanting.

The Third International thus was created, as mentioned in one of the commentaries in this series, to pick up the fallen banner of international socialism after the betrayals of the Second International. More importantly, it was the first international organization that took upon itself in its early, heroic revolutionary days, at least, the strategic question of how to make, and win, a revolution in the age of world imperialism. The Trotsky-led effort of creating a Fourth International in the 1930s, somewhat stillborn as it turned out to be, nevertheless based itself, correctly, on those early days of the Comintern. So in some of the specific details of the posts in this year’s series, highlighting the 90th anniversary of the Third World Congress this is “just” history, but right underneath, and not far underneath at that, are rich lessons for us to ponder today.

******

First Congress of the Communist International

The International Situation and the Policy of the Entente

Source: Theses Resolutions and Manifestos of the First Four Congress of the Third International, translated by Alix Holt and Barbara Holland. Ink Links 1980;

Transcribed: by Andy Blunden.

6 March, 1919

Theses

The experience of the imperialist war has helped to unmask completely the imperialist policy of the bourgeois ‘democracies’ as being the struggle of states to carve up the world and consolidate the economic and political dictatorship of finance capital over the exploited and oppressed masses. The war has resulted in the killing and maiming of millions of people, the enslavement of the proletariat, the destruction of the middle classes, the incredible enrichment of the upper sections of the bourgeoisie through war contracts, loans, etc. and the triumph of military reaction in every country – and, in consequence, illusions of national defence, civil peace and ‘democracy’ are being destroyed. The policy of peace-making reveals the true aims of imperialists everywhere; it demonstrates, once and for all, the real nature of imperialism.

The Brest-Litovsk Peace and the Unmasking of German Imperialism

Brest-Litovsk and the subsequent Treaty of Bucharest have revealed the rapacious and reactionary character of the imperialism of the Central Powers. The victors have wrung annexations and indemnities from defenceless Russia. The principle of the self-determination of peoples has been a fig-leaf, hiding a policy of annexations: vassal states have been created, whose reactionary governments have aided the policy of plunder and suppressed the revolutionary movement of the labouring masses. German imperialism was not an outright victor in the international struggle and was therefore unable, at that time, to show itself in its true colours. It was forced to live in an uneasy peace with Soviet Russia, cloaking its predatory and reactionary policy with hypocritical phrases.

The Entente powers, who proved victorious in the World War, threw off their mask to show the true face of world imperialism.

The Victory of the Entente and the Alignment of States

The victory of the Entente powers has divided the so-called civilised countries of the world into several groups. The first of these includes the rulers of the capitalist world, the imperialist Great Powers victorious in the war (Britain, America, France, Japan, Italy). Opposed to them are the imperialist countries broken by their defeat in the war and undermined by the outbreak of proletarian revolution (Germany, Austria, Hungary and their formal vassals). The vassal states of the Entente form the third group. They include the small capitalist countries that entered the war on the side of the Entente (Belgium, Serbia, Portugal and others), and also the newly established national republics and buffer-states (the Czechoslovak republic, Poland, the Russian White Guard republics and others). The neutral states are in a position similar to that of the vassal states, but they are subject to strong economic and political pressures, as a result of which their position frequently resembles that of the defeated states. The Russian socialist republic is a workers’ and peasants’ state, standing outside the capitalist world and representing a great social threat to triumphant imperialism – the threat that all the fruits of victory will be destroyed by the onslaught of world revolution.

Entente Imperialism’s ‘Peace Policy'; Imperialism Reveals its True Nature

Taken as a whole, the ‘peace policy’ of the five great lords of the world, the Entente Powers, has revealed and continues to reveal the true nature of imperialism.

Notwithstanding all the phrases about a ‘democratic foreign policy’, it represents the complete triumph of secret diplomacy, which decides the fate of the world by deals between the agents of the financial trusts, arranged behind the backs and at the expense of the labouring millions of the world. AU important questions without exception are decided in Paris by the committee of the five powers, at closed sessions and in the absence of representatives of the defeated, neutral or even vassal states.

The speeches of Lloyd George, Clemenceau, Sonnino and others openly proclaim and accept the need for annexations and indemnities at the expense of the vanquished.

In spite of all the talk of ‘a war for universal disarmament’, the necessity of further armament and in particular the maintenance of British naval power to ‘safeguard the freedom of the seas’. as it is called, is openly proclaimed.

The principle of the self-determination of peoples, officially recognised by the Entente is, in practice, trampled underfoot and instead the disputed territories are divided between the ruling states and their vassals. Alsace-Lorraine has been incorporated into France without its population being consulted. Ireland, India and Egypt are denied the right of self-determination; the Yugoslav government and the Czechoslovak republic are being established by armed force, shameless bargaining is going on over the division of European and Asiatic Turkey, the redistribution of the German colonies has begun, etc.

The policy of indemnities has been pursued to a point where the vanquished states are being stripped bare. Not only are these countries presented with bills that run into billions, not only are their military means confiscated, they are being robbed by the Entente countries of their steam engines, carriages, ships, agricultural machinery, gold stocks, etc. In addition, prisoners of war are being turned into slave labourers for the victors. Projects are being put forward to introduce compulsory labour service for the German workers, whom the powers of the Entente want to transform into penniless and hungry slaves of Entente capital.

The policy of extreme national misanthropy is expressed in the ceaseless campaign waged against the vanquished nationalities in the press of the Entente Powers and the occupying powers, and in the blockade, which threatens the peoples of Germany and Austria with death by starvation. This policy encourages pogroms against the German population by the accomplices of the Entente – the Czech and Polish chauvinists – and pogroms against the Jewish population that overshadow all the exploits of Russian Tsarism.

The ‘democratic’ states of the Entente are conducting a policy of extreme reaction.

Reaction is triumphing in the Entente countries – France, for instance, has returned to the blackest times of Napoleon III’s rule – and in all the countries of the capitalist world which come within the Entente sphere of influence. The Allies are stifling the revolution in the occupied territories of Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, etc.; they are turning the bourgeois-collaborationist governments of the vanquished countries against the revolutionary workers, by threatening them with the withdrawal of food supplies. The Allies have declared they will sink German ships which dare to raise the red flag of revolution; they have refused to recognise the German Soviets; they have abolished the eight-hour working day in the occupied German territories. Besides directly supporting reactionary policies in the neutral countries, and forcibly promoting them in the vassal states (the Paderewski regime in Poland), they are inciting the reactionary forces of these countries (Finland, Poland, Sweden, etc.) against revolutionary Russia and demanding the intervention of the German armed forces.

Contradictions among the Entente Powers

A number of deep contradictions are emerging among the Great Powers which rule the capitalist world, in spite of the similarity of the fundamental features of their imperialist policy.

These contradictions centre, in the main, around the peace programme of American finance capital (the so-called Wilson programme).

The most important points of this programme are: ‘freedom of the seas’, the ‘League of Nations’ and ‘internationalisation of the colonies’. The slogan ‘freedom of the seas’ – stripped of its hypocritical mask – means, in fact, the abolition of the naval supremacy of certain great powers (above all, Britain), and the opening of all sea routes to American trade. ‘League of Nations’ would mean that the European powers (in the first place, France) lose the right to subjugate directly and annex weaker states and peoples. ‘Internationalisation of the colonies’ establishes the same rule in relation to the colonial territories.

The content of the programme is explained by the fact that since American capital does not possess the world’s largest fleet, it lacks the opportunity of carrying out direct annexations in Europe and therefore strives to exploit the weak states and peoples through trade and capital investment. American capital aims at forcing the other powers to form a syndicate of State-Trusts to supervise the ‘just’ division of opportunities for exploitation, while reducing the struggle between these State-Trusts to a purely economic one. In the field of economic exploitation, highly-developed American finance capital can count on achieving the leading position, thus ensuring its economic and political supremacy in the world.

The policy of ‘freedom of the seas’ conflicts sharply with the interests of Britain, Japan and, to some extent, of Italy (in the Adriatic). The establishment of a ‘League of Nations’ and the ‘Internationalisation of the colonies’ are in fundamental conflict with the interests of other imperialist powers. In France, where finance capital still retains features of money-lending, industry is weakly developed and the productive forces were completely destroyed in the war, the imperialists are prepared to support the capitalist system by the most extreme methods: the barbaric plunder of Germany, the direct subjugation and intense exploitation of vassal states (the proposals for a Danubian federation, the Yugoslav state), and the forcible extraction of money from the Russian people as repayment for the heavy loans contracted with the French Shylock. France and Italy (and, in a different way, Japan) can also, by virtue of being continental powers, pursue a policy of direct annexations.

While the interests of the Great Powers conflict with those of America, they also conflict with one another. Britain is afraid of France strengthening its position on the continent, while the interests of Britain and France in Asia Minor and Africa are incompatible. Italian interests in the Balkan Peninsula and the Tyrol clash with French interests. Japan disputes the Pacific islands with British Australia, etc.

Groups and Currents in the Ranks of the Entente

The contradictions among the Great Powers are leading to the development of various groupings within the ranks of the Entente. Two main groupings have so far emerged: the first includes France, Britain and Japan, and is directed against America and Italy, while the second involves Britain and America and opposes the other Great Powers. The first alignment was predominant up until the beginning of January 1919, when President Wilson dropped his demand for the abolition of British naval supremacy. The development of the revolutionary workers’ and soldiers’ movement in Britain has forced the imperialists of different countries to recognise the need for a mutual agreement, an end to their Russian adventure and the rapid conclusion of peace. Hence, the pro-American current is gaining strength. Since January 1919, it has been the dominant alignment. The Anglo-American bloc is opposed to the preferential right of France to plunder Germany and is against this right being invoked too indiscriminately. It seeks to reduce the excessive annexation demands made by France, Italy and Japan and prevent the latter from establishing direct control over the recently created vassal states. With regard to the Russian question, it is more inclined to favour peace, for it wants a free hand to conclude the division of the world before strangling the European revolution and, finally, turning to crush the revolution in Russia.

These two alignments correspond to the two currents, the one extreme annexationist and the other more moderate; the Wilson-Lloyd George grouping supports the moderate policy.

The ‘League of Nations'

In view of the irreconcilable differences that have become apparent among the Entente powers, the ‘League of Nations’, should it come into formal existence, will only have the significance of a holy alliance of capitalists bent on crushing the workers’ revolution. Propaganda for the ‘League of Nations’, though, is the best way of confusing the revolutionary consciousness of the working class. It replaces the idea of an International of revolutionary workers’ republics with the idea of an international association, of sham democracies, attainable through a coalition between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie.

The ‘League of Nations’ is a deceptive slogan employed by the social-traitors, in their role as errand boys of international capital, to divide the forces of the proletariat and promote the imperialist counter-revolution.

The revolutionary proletariats of all countries of the world must wage a resolute struggle against the Wilsonian notion of a ‘League of Nations’ and protest against entry into this union of plunder, exploitation and imperialist counter-revolution.

Foreign and Domestic Policy in the Defeated States

The crushing military defeat and the internal collapse of Austro-Hungarian imperialism has led, in this first stage of the revolution, to the rule of a bourgeois-collaborationist regime in the central European countries. In the name of democracy and socialism the social-traitors of Germany are pursuing a domestic policy that protects and restores the economic rule and the political dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, and a foreign policy that aims to revive Germany imperialism by demanding the return of the colonies and the inclusion of Germany in the grasping ‘League of Nations’. The ‘Great Power’ aspirations of the German bourgeoisie and the social-traitors grow, as the White Guard bands within Germany find a firm base and as stability in the Entente camp deteriorates. At the same time the bourgeois-collaborationist governments carry out the counter-revolutionary instructions of the Entente which includes a policy of inciting the German workers against the. Russian workers’ revolution. This is to the benefit of the Entente, but it undermines the international solidarity of the proletariat. The policy of the bourgeoisie and the social-opportunists in Austria and Hungary is a repetition, in an attenuated form, of the policy of the bourgeois-collaborationist bloc in Germany.

The Vassal States of the Entente

In the vassal states and the states recently created by the Entente (Czechoslovakia, the Yugoslav state, Poland, Finland, etc.) the policy of Entente imperialism is based on the ruling classes and the social-nationalists, and is directed at the establishment of a pole of attraction for a national counter-revolutionary movement. The purpose of the movement is to keep a cheek on the vanquished nations and regulate the power of the newly formed states by fomenting struggles between them, thus keeping them subordinate to the Entente. It is also to serve as a brake on the revolutionary movement, which is developing in the heart of the new ‘national’ republics, and, finally, to train White Guard cadres for the struggle with the international revolution, in particular the Russian revolution.

As to Belgium, Portugal, Greece and other small states allied with the Entente, their policy is entirely determined by the policy of the large ‘predators’, on whom they are entirely dependent and to whom they turn for help in securing the less important annexations and indemnities.

The Neutral States

The neutral states find themselves in the position of unprivileged vassals of Entente imperialism, and are treated little better than the defeated states. A few, who are in favour with the Entente, make various demands on the enemies of the Entente (Denmark claims Flensburg, Switzerland demands the internationalisation of the Rhine, etc.). At the same time they run the counter-revolutionary errands of the Entente (Russian embassies are expelled, White Guards are recruited in Scandinavia and elsewhere, etc.). The less fortunate are threatened with territorial dismemberment (the plan for uniting Dutch Limburg with Belgium and the internationalisation of the mouth of the Scheldt are examples).

The Entente and Soviet Russia

The predatory, anti-humanitarian and reactionary character of Entente imperialism is most clearly shown in its policy toward Soviet Russia. From the first day of the October revolution the Entente powers took the side of the counter-revolutionary parties and governments of Russia. With the support of the bourgeois counter-revolutionaries they have seized Siberia, the Urals, the coastal areas of European Russia, the Caucasus and a part of Turkestan. The Allies have taken, and are continuing to take, raw materials from the occupied areas. With the assistance of Czechoslovak bands of mercenaries, they have stolen the gold reserves of the Russian state. Under the leadership of the British diplomat, Lockhart, French and British spies have contrived to blow up bridges, railways and trains, thereby obstructing the distribution of food supplies. The allies have supplied money, arms and military aid to the reactionary generals Denikin, Kolchak and Krasnov, who have hanged and shot thousands of workers and peasants in Rostov, Yusovka, Novorossiisk, Omsk, etc.

Through Clemenceau and Pichon, the Entente has openly proclaimed the principles of ‘economic encirclement’, that is, of starving to death the revolutionary republic of workers and peasants, and promised ‘technical support’ to the bands of Denikin, Kolchak and Krasnov.

The Entente has consistently rejected the repeated peace proposals of the Soviet republic.

On 23 January, 1919, the Entente powers, among whom the moderate current was, at the time, gaining strength, invited all Russian governments to send representatives ‘to the island of Prinkipo. There was undoubtedly an element of provocation in this action. On 4 February the Entente received an affirmative answer from the Soviet government, expressing the readiness of Soviet power to agree to annexations,

indemnities and concessions in order to save the Russian workers and peasants from the war the Allies were forcing upon them. The Entente failed to reply to this peaceful proposal –

This is evidence that the annexationist-reactionary tendencies among the Entente imperialists have a firm basis. They are threatening the socialist republics with new annexations and counter-revolutionary attacks.

Thus its ‘peace policy’ conclusively reveals the essence of Entente imperialism, and of imperialism in general, to the international proletariat. It also shows that the imperialist governments are unable to conclude a just and stable peace and that finance capital is not capable of restoring the ruined economy. The continued rule of finance capital will lead either to the complete destruction of civilised society or to an unprecedented increase in the level of exploitation, and enslavement, to political reaction and a policy of armament, and eventually to new destructive wars.

Markin comment:

Some anniversaries, like those marking the publication of a book, play or poem, are worthy of remembrance every five, ten, or twenty-five years. Other more world historic events like the remembrance of the Paris Commune of 1871, the Bolshevik Russian Revolution of 1917, and, as here, the founding of the Communist International (also known as the Third International, Comintern, and CI) in 1919 are worthy of yearly attention. Why is that so in the case of the long departed (1943, by Stalin fiat) and, at the end unlamented, Comintern? That is what this year’s remembrance, through CI documentation and other commentary, will attempt to impart on those leftist militants who are serious about studying the lessons of our revolutionary, our communist revolutionary past.

No question that the old injunction of Marx and Engels as early as the Communist Manifesto that the workers of the world needed to unite would have been hollow, and reduced to hortatory holiday speechifying (there was enough of that, as it was) without an organization expression. And they, Marx and Engels, fitfully made their efforts with the all-encompassing pan-working class First International. Later the less all encompassing but still party of the whole class-oriented socialist Second International made important, if limited, contributions to fulfilling that slogan before the advent of world imperialism left its outlook wanting, very wanting.

The Third International thus was created, as mentioned in one of the commentaries in this series, to pick up the fallen banner of international socialism after the betrayals of the Second International. More importantly, it was the first international organization that took upon itself in its early, heroic revolutionary days, at least, the strategic question of how to make, and win, a revolution in the age of world imperialism. The Trotsky-led effort of creating a Fourth International in the 1930s, somewhat stillborn as it turned out to be, nevertheless based itself, correctly, on those early days of the Comintern. So in some of the specific details of the posts in this year’s series, highlighting the 90th anniversary of the Third World Congress this is “just” history, but right underneath, and not far underneath at that, are rich lessons for us to ponder today.

******

First Congress of the Communist International

The International Situation and the Policy of the Entente

Source: Theses Resolutions and Manifestos of the First Four Congress of the Third International, translated by Alix Holt and Barbara Holland. Ink Links 1980;

Transcribed: by Andy Blunden.

6 March, 1919

Theses

The experience of the imperialist war has helped to unmask completely the imperialist policy of the bourgeois ‘democracies’ as being the struggle of states to carve up the world and consolidate the economic and political dictatorship of finance capital over the exploited and oppressed masses. The war has resulted in the killing and maiming of millions of people, the enslavement of the proletariat, the destruction of the middle classes, the incredible enrichment of the upper sections of the bourgeoisie through war contracts, loans, etc. and the triumph of military reaction in every country – and, in consequence, illusions of national defence, civil peace and ‘democracy’ are being destroyed. The policy of peace-making reveals the true aims of imperialists everywhere; it demonstrates, once and for all, the real nature of imperialism.

The Brest-Litovsk Peace and the Unmasking of German Imperialism

Brest-Litovsk and the subsequent Treaty of Bucharest have revealed the rapacious and reactionary character of the imperialism of the Central Powers. The victors have wrung annexations and indemnities from defenceless Russia. The principle of the self-determination of peoples has been a fig-leaf, hiding a policy of annexations: vassal states have been created, whose reactionary governments have aided the policy of plunder and suppressed the revolutionary movement of the labouring masses. German imperialism was not an outright victor in the international struggle and was therefore unable, at that time, to show itself in its true colours. It was forced to live in an uneasy peace with Soviet Russia, cloaking its predatory and reactionary policy with hypocritical phrases.

The Entente powers, who proved victorious in the World War, threw off their mask to show the true face of world imperialism.

The Victory of the Entente and the Alignment of States

The victory of the Entente powers has divided the so-called civilised countries of the world into several groups. The first of these includes the rulers of the capitalist world, the imperialist Great Powers victorious in the war (Britain, America, France, Japan, Italy). Opposed to them are the imperialist countries broken by their defeat in the war and undermined by the outbreak of proletarian revolution (Germany, Austria, Hungary and their formal vassals). The vassal states of the Entente form the third group. They include the small capitalist countries that entered the war on the side of the Entente (Belgium, Serbia, Portugal and others), and also the newly established national republics and buffer-states (the Czechoslovak republic, Poland, the Russian White Guard republics and others). The neutral states are in a position similar to that of the vassal states, but they are subject to strong economic and political pressures, as a result of which their position frequently resembles that of the defeated states. The Russian socialist republic is a workers’ and peasants’ state, standing outside the capitalist world and representing a great social threat to triumphant imperialism – the threat that all the fruits of victory will be destroyed by the onslaught of world revolution.

Entente Imperialism’s ‘Peace Policy'; Imperialism Reveals its True Nature

Taken as a whole, the ‘peace policy’ of the five great lords of the world, the Entente Powers, has revealed and continues to reveal the true nature of imperialism.

Notwithstanding all the phrases about a ‘democratic foreign policy’, it represents the complete triumph of secret diplomacy, which decides the fate of the world by deals between the agents of the financial trusts, arranged behind the backs and at the expense of the labouring millions of the world. AU important questions without exception are decided in Paris by the committee of the five powers, at closed sessions and in the absence of representatives of the defeated, neutral or even vassal states.

The speeches of Lloyd George, Clemenceau, Sonnino and others openly proclaim and accept the need for annexations and indemnities at the expense of the vanquished.

In spite of all the talk of ‘a war for universal disarmament’, the necessity of further armament and in particular the maintenance of British naval power to ‘safeguard the freedom of the seas’. as it is called, is openly proclaimed.

The principle of the self-determination of peoples, officially recognised by the Entente is, in practice, trampled underfoot and instead the disputed territories are divided between the ruling states and their vassals. Alsace-Lorraine has been incorporated into France without its population being consulted. Ireland, India and Egypt are denied the right of self-determination; the Yugoslav government and the Czechoslovak republic are being established by armed force, shameless bargaining is going on over the division of European and Asiatic Turkey, the redistribution of the German colonies has begun, etc.

The policy of indemnities has been pursued to a point where the vanquished states are being stripped bare. Not only are these countries presented with bills that run into billions, not only are their military means confiscated, they are being robbed by the Entente countries of their steam engines, carriages, ships, agricultural machinery, gold stocks, etc. In addition, prisoners of war are being turned into slave labourers for the victors. Projects are being put forward to introduce compulsory labour service for the German workers, whom the powers of the Entente want to transform into penniless and hungry slaves of Entente capital.

The policy of extreme national misanthropy is expressed in the ceaseless campaign waged against the vanquished nationalities in the press of the Entente Powers and the occupying powers, and in the blockade, which threatens the peoples of Germany and Austria with death by starvation. This policy encourages pogroms against the German population by the accomplices of the Entente – the Czech and Polish chauvinists – and pogroms against the Jewish population that overshadow all the exploits of Russian Tsarism.

The ‘democratic’ states of the Entente are conducting a policy of extreme reaction.

Reaction is triumphing in the Entente countries – France, for instance, has returned to the blackest times of Napoleon III’s rule – and in all the countries of the capitalist world which come within the Entente sphere of influence. The Allies are stifling the revolution in the occupied territories of Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, etc.; they are turning the bourgeois-collaborationist governments of the vanquished countries against the revolutionary workers, by threatening them with the withdrawal of food supplies. The Allies have declared they will sink German ships which dare to raise the red flag of revolution; they have refused to recognise the German Soviets; they have abolished the eight-hour working day in the occupied German territories. Besides directly supporting reactionary policies in the neutral countries, and forcibly promoting them in the vassal states (the Paderewski regime in Poland), they are inciting the reactionary forces of these countries (Finland, Poland, Sweden, etc.) against revolutionary Russia and demanding the intervention of the German armed forces.

Contradictions among the Entente Powers

A number of deep contradictions are emerging among the Great Powers which rule the capitalist world, in spite of the similarity of the fundamental features of their imperialist policy.

These contradictions centre, in the main, around the peace programme of American finance capital (the so-called Wilson programme).

The most important points of this programme are: ‘freedom of the seas’, the ‘League of Nations’ and ‘internationalisation of the colonies’. The slogan ‘freedom of the seas’ – stripped of its hypocritical mask – means, in fact, the abolition of the naval supremacy of certain great powers (above all, Britain), and the opening of all sea routes to American trade. ‘League of Nations’ would mean that the European powers (in the first place, France) lose the right to subjugate directly and annex weaker states and peoples. ‘Internationalisation of the colonies’ establishes the same rule in relation to the colonial territories.

The content of the programme is explained by the fact that since American capital does not possess the world’s largest fleet, it lacks the opportunity of carrying out direct annexations in Europe and therefore strives to exploit the weak states and peoples through trade and capital investment. American capital aims at forcing the other powers to form a syndicate of State-Trusts to supervise the ‘just’ division of opportunities for exploitation, while reducing the struggle between these State-Trusts to a purely economic one. In the field of economic exploitation, highly-developed American finance capital can count on achieving the leading position, thus ensuring its economic and political supremacy in the world.

The policy of ‘freedom of the seas’ conflicts sharply with the interests of Britain, Japan and, to some extent, of Italy (in the Adriatic). The establishment of a ‘League of Nations’ and the ‘Internationalisation of the colonies’ are in fundamental conflict with the interests of other imperialist powers. In France, where finance capital still retains features of money-lending, industry is weakly developed and the productive forces were completely destroyed in the war, the imperialists are prepared to support the capitalist system by the most extreme methods: the barbaric plunder of Germany, the direct subjugation and intense exploitation of vassal states (the proposals for a Danubian federation, the Yugoslav state), and the forcible extraction of money from the Russian people as repayment for the heavy loans contracted with the French Shylock. France and Italy (and, in a different way, Japan) can also, by virtue of being continental powers, pursue a policy of direct annexations.

While the interests of the Great Powers conflict with those of America, they also conflict with one another. Britain is afraid of France strengthening its position on the continent, while the interests of Britain and France in Asia Minor and Africa are incompatible. Italian interests in the Balkan Peninsula and the Tyrol clash with French interests. Japan disputes the Pacific islands with British Australia, etc.

Groups and Currents in the Ranks of the Entente

The contradictions among the Great Powers are leading to the development of various groupings within the ranks of the Entente. Two main groupings have so far emerged: the first includes France, Britain and Japan, and is directed against America and Italy, while the second involves Britain and America and opposes the other Great Powers. The first alignment was predominant up until the beginning of January 1919, when President Wilson dropped his demand for the abolition of British naval supremacy. The development of the revolutionary workers’ and soldiers’ movement in Britain has forced the imperialists of different countries to recognise the need for a mutual agreement, an end to their Russian adventure and the rapid conclusion of peace. Hence, the pro-American current is gaining strength. Since January 1919, it has been the dominant alignment. The Anglo-American bloc is opposed to the preferential right of France to plunder Germany and is against this right being invoked too indiscriminately. It seeks to reduce the excessive annexation demands made by France, Italy and Japan and prevent the latter from establishing direct control over the recently created vassal states. With regard to the Russian question, it is more inclined to favour peace, for it wants a free hand to conclude the division of the world before strangling the European revolution and, finally, turning to crush the revolution in Russia.

These two alignments correspond to the two currents, the one extreme annexationist and the other more moderate; the Wilson-Lloyd George grouping supports the moderate policy.

The ‘League of Nations'

In view of the irreconcilable differences that have become apparent among the Entente powers, the ‘League of Nations’, should it come into formal existence, will only have the significance of a holy alliance of capitalists bent on crushing the workers’ revolution. Propaganda for the ‘League of Nations’, though, is the best way of confusing the revolutionary consciousness of the working class. It replaces the idea of an International of revolutionary workers’ republics with the idea of an international association, of sham democracies, attainable through a coalition between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie.

The ‘League of Nations’ is a deceptive slogan employed by the social-traitors, in their role as errand boys of international capital, to divide the forces of the proletariat and promote the imperialist counter-revolution.

The revolutionary proletariats of all countries of the world must wage a resolute struggle against the Wilsonian notion of a ‘League of Nations’ and protest against entry into this union of plunder, exploitation and imperialist counter-revolution.

Foreign and Domestic Policy in the Defeated States

The crushing military defeat and the internal collapse of Austro-Hungarian imperialism has led, in this first stage of the revolution, to the rule of a bourgeois-collaborationist regime in the central European countries. In the name of democracy and socialism the social-traitors of Germany are pursuing a domestic policy that protects and restores the economic rule and the political dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, and a foreign policy that aims to revive Germany imperialism by demanding the return of the colonies and the inclusion of Germany in the grasping ‘League of Nations’. The ‘Great Power’ aspirations of the German bourgeoisie and the social-traitors grow, as the White Guard bands within Germany find a firm base and as stability in the Entente camp deteriorates. At the same time the bourgeois-collaborationist governments carry out the counter-revolutionary instructions of the Entente which includes a policy of inciting the German workers against the. Russian workers’ revolution. This is to the benefit of the Entente, but it undermines the international solidarity of the proletariat. The policy of the bourgeoisie and the social-opportunists in Austria and Hungary is a repetition, in an attenuated form, of the policy of the bourgeois-collaborationist bloc in Germany.

The Vassal States of the Entente

In the vassal states and the states recently created by the Entente (Czechoslovakia, the Yugoslav state, Poland, Finland, etc.) the policy of Entente imperialism is based on the ruling classes and the social-nationalists, and is directed at the establishment of a pole of attraction for a national counter-revolutionary movement. The purpose of the movement is to keep a cheek on the vanquished nations and regulate the power of the newly formed states by fomenting struggles between them, thus keeping them subordinate to the Entente. It is also to serve as a brake on the revolutionary movement, which is developing in the heart of the new ‘national’ republics, and, finally, to train White Guard cadres for the struggle with the international revolution, in particular the Russian revolution.

As to Belgium, Portugal, Greece and other small states allied with the Entente, their policy is entirely determined by the policy of the large ‘predators’, on whom they are entirely dependent and to whom they turn for help in securing the less important annexations and indemnities.

The Neutral States

The neutral states find themselves in the position of unprivileged vassals of Entente imperialism, and are treated little better than the defeated states. A few, who are in favour with the Entente, make various demands on the enemies of the Entente (Denmark claims Flensburg, Switzerland demands the internationalisation of the Rhine, etc.). At the same time they run the counter-revolutionary errands of the Entente (Russian embassies are expelled, White Guards are recruited in Scandinavia and elsewhere, etc.). The less fortunate are threatened with territorial dismemberment (the plan for uniting Dutch Limburg with Belgium and the internationalisation of the mouth of the Scheldt are examples).

The Entente and Soviet Russia

The predatory, anti-humanitarian and reactionary character of Entente imperialism is most clearly shown in its policy toward Soviet Russia. From the first day of the October revolution the Entente powers took the side of the counter-revolutionary parties and governments of Russia. With the support of the bourgeois counter-revolutionaries they have seized Siberia, the Urals, the coastal areas of European Russia, the Caucasus and a part of Turkestan. The Allies have taken, and are continuing to take, raw materials from the occupied areas. With the assistance of Czechoslovak bands of mercenaries, they have stolen the gold reserves of the Russian state. Under the leadership of the British diplomat, Lockhart, French and British spies have contrived to blow up bridges, railways and trains, thereby obstructing the distribution of food supplies. The allies have supplied money, arms and military aid to the reactionary generals Denikin, Kolchak and Krasnov, who have hanged and shot thousands of workers and peasants in Rostov, Yusovka, Novorossiisk, Omsk, etc.

Through Clemenceau and Pichon, the Entente has openly proclaimed the principles of ‘economic encirclement’, that is, of starving to death the revolutionary republic of workers and peasants, and promised ‘technical support’ to the bands of Denikin, Kolchak and Krasnov.

The Entente has consistently rejected the repeated peace proposals of the Soviet republic.

On 23 January, 1919, the Entente powers, among whom the moderate current was, at the time, gaining strength, invited all Russian governments to send representatives ‘to the island of Prinkipo. There was undoubtedly an element of provocation in this action. On 4 February the Entente received an affirmative answer from the Soviet government, expressing the readiness of Soviet power to agree to annexations,

indemnities and concessions in order to save the Russian workers and peasants from the war the Allies were forcing upon them. The Entente failed to reply to this peaceful proposal –

This is evidence that the annexationist-reactionary tendencies among the Entente imperialists have a firm basis. They are threatening the socialist republics with new annexations and counter-revolutionary attacks.

Thus its ‘peace policy’ conclusively reveals the essence of Entente imperialism, and of imperialism in general, to the international proletariat. It also shows that the imperialist governments are unable to conclude a just and stable peace and that finance capital is not capable of restoring the ruined economy. The continued rule of finance capital will lead either to the complete destruction of civilised society or to an unprecedented increase in the level of exploitation, and enslavement, to political reaction and a policy of armament, and eventually to new destructive wars.