Thoughts Upon The Demise

Of A Poker Princess-Jessica Chastain’s “Molly’s Game” (2017)-A Film Review-Of

Sorts

DVD Review

By Sam Lowell, former

film editor of American Left History

and of the American Film Gazette now

emeritus at the latter and a contributing reviewer at the former if anybody

needs my credential, my professional CV if you like

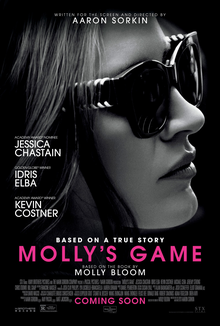

Molly’s Game, starring Jessica

Chastain, Idris Elba, Kevin Costner but he is only window dressing on this one because

the former two carry this film, 2017

I am mad as hell and I

am not going to take it anymore. Yes, I know that these are famous words that Peter

Finch uttered to a sullen world back in the 1970s as a newscaster in the

definitive film Network. They fit the

occasion however since whatever ailed Brother Finch in those times has got me

is a serious snit. As I made sure that I mentioned after my by-line space, a

by-line that I have labored in the vineyards of the film industry, book industry

too, hell, the art industry when I needed fast money to pay back alimony or the

parcel of kids, nice kids, that my three ex-wives and I raised needed college

money and until recently, very recently that designation had not been

challenged, had not been sullied by young upstarts trying to make a name for

themselves now that I am no longer reviewing on a daily basis-praise be.

If the kids want war,

hell, I am more than willing to oblige since we seem to have gone down the

slippery slope away from social cohesion and not just of account of the Bozo

who is running the asylum in Washington at the moment. Over the past few weeks

two young, up and coming journalists, reviewers I guess they would call

themselves and from what I have read of their reviews they may in fact have

promising futures-if they ever get their facts right and maybe stop hanging on

my old friend Seth Garth’s every word like it had come down from the

mountain-have flat out attempted to besmirch, yes, besmirch is the only word

that comes readily to mind my reputation. Everyone knows, or should know,

should be assumed to know, that this review business, film, books, music,

culture is a tough racket, is as one of the youngsters wrote a “dog eat dog”

environment and I will admit, admit freely that when I was young and hungry I

was as apt to try to cut up my competitors, hell, my fellow writers wherever I

landed as anybody else-as long as I got my facts right. Just ask Seth Garth who

still carries the scars from our battles as I do his.

What these two writers,

hell, what Sarah Lemoyne and subsequently young Will Bradley have been running

around erroneously trying to sell a distracted public is that back in the day,

back after I got my coveted by-line I started “mailing it in,” started having

stringers, mostly young fresh females from one of the Seven Sisters colleges

that Allan loved to hire to give the place some swag and some eye candy when

there were mostly older guys writing their brains out here write my reviews for

me. Still worse have accused me of, when desperate, taking whatever press

releases the studio public relations departments were putting out, clipping off

the tops and sending the rest off as my review so that I could keep drinking

and cavorting with women which I freely admit I liked, still like to do-with

one woman anyway. Will picked up on these Sarah comments and extended it to his

view that while I indeed was the master of the film noir genre in my time after

my major definitive book on the subject came out, a book which one and all,

even these pups continue to recognize as the “go to” book on film noir I didn’t

have a blessed original idea. Had gone the college professor route (and me

without even a college degree to my name) and lived off that one big idea

through a fistful of conferences, lectures and speaking engagements.

That last comment was

what pretty much broke the camel’s back, no, that and the snide insinuation by

Will that the only reason that I still was being published on a regular basis

and syndicated a few places was that I had been the key vote that ejected my

old friend Allan Jackson from the site manager position at this publication and

that new manager Greg Green “owed” his job to my decisive intervention.

Needless to say with all of that in the basket I immediately went to Greg and

asked for the next available review so that I could respond to these wild and

wooly children. In the interest of fairness Greg agreed (and not as I am sure

will become the “real” reason among certain youngsters that I had “bought” him)

and so I got this freaking suck-ass review of Molly’s Game about some smarty-pants ex-jock, played by comely

Jessica Chastain, who landed on her feet for a while running on the cuff poker

games for rich and famous Alpha males until she got caught in the “feds” bind,”

got caught holding the bag. Everybody knows my thing is film noir and other

older stuff but I had to take this stinker, well, not stinker because the

acting is good and the story line is kind of interesting but who could really

care about the trials and tribulations of some over-the-hill jock who couldn’t

make the cut, ice-skating, no, I think it was free-form skiing something like

that.

I will get to the damn

thing in my own good time and still I have probably already given you enough of

the “skinny,” the theme if you don’t know what skinny is for you to judge right

now whether you want to spend a couple of hours watching the drama unfold. My

long-time companion Laura Perkins who writes here occasionally loved it, maybe

because of the strong acting by Jessica somebody who played Molly Bloom (yeah,

everybody who is anybody except maybe Will and Sarah will gladly steal whatever

they can from James Joyce even names named) but I got drowsy about half way

through. Like I said this is about setting the record straight about my now

besmirched career as about reviewing this baffling film. In any case since Greg

has again in the interest of fairness told me that I will have another review

to tackle Will Bradley’s allegations I am on the scent of one Sarah Lemoyne

today who claimed in her cherished review of the original Star Wars episode from 1977 that she had researched her allegations

about my so-called “mailing it in” practices. (Jesus was Greg serious giving

that old tattered episode and series to her-hell I rejected doing it out of

hand back then when I worked for the legendary Cal Clark over at the Gazette as so much wasted soda and

popcorn on Pa’s credit card.)

I accuse, yeah, like Emil

Zola in anti-Semite Dreyfus times who one can also fruitfully steal from in a

pinch. From what I can gather, and she should be shame-faced but probably won’t

be if it is true, Sarah’s source for her accusations was, is one Leslie Dumont

who after years at Women Today where

she had a big and deserved by-line came back here to do occasional writing in

her retirement. Hell, I was the one, along with her then boyfriend Josh Breslin

(who in the now obligatory interest of transparency also writes here now), who

got her to apply for that Women Today

job when Allan Jackson was only taking care of good old boys and she was

wasting her time as a stringer. A stringer for me on occasion.

Here is what Sarah

didn’t bother to ask about, didn’t even probably have a clue to ask about since

they don’t teach this kind of thing in those vaunted Seven Sisters and

journalism graduate schools she attended is that despite her boyfriend Josh Leslie

was “making a play for me.” Truth, ask her, ask Josh. I admit I asked Leslie to

write a few pieces, maybe half a dozen, not a million like Sarah implied before

I realized that she was interested in me romantically. I will further admit

that in those days I was in an alcoholic/drug daze half the time along with

half the guys on the staff, not Josh though, not that I remember. But then I

was going through the last phases of my first divorce, was playing around and

had no desire to upset any more apple-carts. Sarah, anybody looking for truth check

it out. I prided myself on my reviews, saw my by-line not as a privilege but an

obligation to do the best I could even under those hazes.

As for the allegations

that I would take studio public relations department press releases and sent

them to Allan as Sam’s pure gold. Sure I did that for some, some turkeys like The Return Of Godzilla, Sandy Dee Doesn’t

Live Here Anymore, Benny’s Beach Blanket Bingo, stuff that should never

have seen the light of day, stuff that any self-respecting journalist would

take a flyer on. What Sarah forgot to ask Leslie, or Leslie “neglected” to

mention was that everybody did it, everybody who saw a turkey and would rather

face Satan himself in all his fire than have to write two words of original

material on the damn thing. And that included Leslie when she went to Women Today. Ask her. If that isn’t enough egg on your face for one

day then come at me again. Yeah, this is a cutthroat business, always has been

and always will be. Tell your boy Will I am coming for him next.

Oh yeah, the film. Like

I said not my cup of tea and maybe a little long-winded going through the legal

process which Molly Bloom, the notorious poker princess, the notorious

real-life poker princess according to the cover blurbs and the front end film introduction

although I admit although I love games of chance, like the horse too I didn’t know

who she was, had to face before a little rough justice. Not film noir rough

justice with some avenging angel private detective clearing the way for her

taking some slugs if necessary but a good and capable lawyer who gave as good

and he got. Charlie Jaffey, played by Idris Elba. He measured up to Molly’s

expectations of what she would have been like as a Harvard Law School lawyer if

she hadn’t been waylaid by that whole mock skiing jock stuff which went bust

before she could hop on the gravy train. Unemployed and unemployable since who

wants snow bunnies who have given up the ghost of Olympic gold, have failed one

way or another, to sell their skis and sneakers Molly heads to sunny LA to thaw

out for a while.

She does a little of

this and a little of that, cocktail waitress, the usual until she hits “pay-dirt”

with a guy who has been running, implausibly given his dirt-bagging Molly, high

stakes poker games with high profile entertainers and bankers with a taste for

the wild side-and who can pay cash on the barrelhead for their table stakes losses.

Things go along pretty well for a while and the bright and sharp Molly (she

would have made a good lawyer no question one that most lawyers would not want to

have to contest) learns the ins and out of the game. Too well for the grafter

and he fired Molly but she lands on her feet starting her own LA operation

which draws the old crowd in. Plus others recruited in various ways to keep a

pool of players in stock, a smart move. Eventually Molly and her ringer top

player known as Player X part ways and her operation sinks in LA. Some lessons

learned, especially about keeping hands away from the pot, taking her cut which

would have put her at legal risk.

So far so good and Molly heads east to New York to start anew.

No

question Molly is a beauty but already she had had enough

sense to keep business and sex apart, didn’t

get involved with the clientele which would do her no good. It is not clear

since there is no romance in this thriller whether she cared about sex or was too

consumed making the kale to give somebody a tumble. The clientele was probably

driven more by beating high profile X, Y, or Z than sex so that could have been

an angle. In New York she started to run her operation along the lines she set

down in LA. But something changed, she made the biggest mistake of all in

getting wrapped around a heavy drug regimen. Moreover her expansion plans went

awry. Her judgement got clouded, for example, in New York City of all places,

she let a guy named Boris, Yuli, Vladimir, or whatever show up with an off-hand

Monet from off the wall if his “art gallery” in a plain brown wrapping paper as

collateral and she lets him in.

This is where she gets

in way over her head-she is in the crossfire between the FBI, the federal

courts in the city and every bad ass operation from the Russian mafia (you

think maybe the Monet guy might have been “connected”) to the Italian who wanted

in on the action-strong-arming the deadbeats who she was letting play on the

cuff). The only good thing she did through this whole horror show of deceit,

fraud, Ponzi schemes, and letting players ride on her credit line was to get

Jaffey. Why? Well it is always best, just as when you are looking for a private

investigator, when looking for a lawyer to get one who has worked the other side,

been a prosecutor. She got off in the end although she didn’t make a very good

play by turning down a deal to get her dough back for basically finking. That

is to the good in the circles I grew up in. Still she is deep in debt, has a

ton of back taxes and a felony rap on her sheet. In the end she really needed a

corner boy to guide her through this craziness more than a lawyer but given the

situation she at least had that good lawyer. Strong performances by Jessica and

Idris but still not my kind of film-sorry