From

The Labor History Archives -In The 80th Anniversary Year Of The

Great San Francisco, Minneapolis And Toledo General Strikes- Lessons In The

History Of Class Struggle

Longshoreman's Strike of 1934

President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed our nation had a rendezvous with destiny, that is, the American people would survive the Great Depression and achieve unparalleled economic and social well-being. In some ways American labor gained a measure of FDR's dream during the 1930's. After a century of unending struggles for the right of their unions to exist, the New Deal assisted American workers at a time when the national labor movement was declining precipitately in membership.

During June 1933, Congress enacted the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) to combat the economic depression by shortening hours of labor, increasing wages, and eliminating unfair trade practices. The Act also created the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to work with industry and labor to increase employment. Section 7-A of NIRA provided workers the choice of their own representatives to bargain collectively with employers.

On the Pacific Coast, where company unions had dominated industrial relations since the early 1920's, the effect of the federal legislation was to open a new era in employer-employee relations.'

A notable exception to the Pacific Coast labor situation was Tacoma, where ILA Locals 38-3 and 38-30 were the only major closed shop longshore unions on the West Coast.

These locals were respected by both the ILA international office and other Pacific Coast longshoremen for their efficiency and strong leadership. During 1934 Paddy Morris was Pacific Coast ILA Organizer, and Jack Bjorklund was District Secretary. Morris and Bjorklund had spent years trying to organize the West Coast, but until 1929 their organizing drive stumbled along with little progress.

Then worker militancy asserted itself. ILA locals were chartered in Everett and Grays Harbor in 1929. Portland was next in 1931 and Seattle in 1932. When San Francisco, key to the coast, was organized during the fall of 1933, longshoremen were ready to move. By March 1934, forty-four ILA locals held charters in the Pacific Coast District, and longshoremen were once again solidly unionized from San Diego, California, to Juneau, Alaska.

As the Pacific Coast ILA reconstituted itself, district members became involved in developing another important provision of NIRA, Section 7-B. This clause asked industries to voluntarily prepare codes of operation which would stimulate economic recovery and at the same time recognize the needs of working people. From

July 2 trough 5, 1933, a special session of the Pacific Coast District ILA met in Seattle to review a tentative code prepared by Tacoma.

The 56 delegates added or eliminated as they saw fit the various clauses or conditions affecting practically every line of work on the waterfront. The delegates then sent the tentative code with their revisions to the various locals for their acceptance, modification or rejection. The code referendum was overwhelmingly approved by the members .

Pacific Coast District ILA officers, including Jack Bjorklund and Paddy Morris, went to Washington, D.C. with the membership's recommendations for inclusion in the Section B shipping code. When they arrived in the nation's capital city the ILA men discovered that maritime employers already had prepared their version of the code and refused to meet with longshore representatives concerning a joint proposal. Attempts by the NRA bureaucracy to bring the shipping companies to the conference table to discuss the shipping code with the union men were futile.

The shock of the employers' attitude at the code hearings added to the fighting mood of ILA delegates to the Pacific Coast District Convention when they met in San Francisco from February 25 to March 6, 1934. The convention immediately named a negotiating committee to meet with the employers' team, led by Thomas G. Plant, chairman of the San Francisco Water Front Employers.

Chairman Plant kept delaying the meeting with the longshoremen until Paddy Morris, Acting Chairman of the Convention, became so upset with dallying that he stepped down from the podium to advise the delegates:

I want to say that this convention should do this: they should instruct that [negotiating committee] to thresh out the full question at issue with them the employers definitely and positively on Monday and give them an ultimatum that unless they agree to meet with us as a district, that there will be no more meetings with them as local employers. And if they refuse to do that on Monday, you can then decide Goddamned quick what you want to do. And then you can go back to your Local with something material and substantial. If you don't do that, you won't have any Locals, I am afraid . 3

This convention listened to Paddy Morris. The delegates instructed the convention negotiating committee to demand: Recognize the ILA District as the official collective bargaining agent or the convention will take a strike vote. When Jack Bjorklund, negotiating team chairman, reported back to the convention that the employers were willing to talk about wages and working conditions, but not on the closed shop situation, the following resolution was proposed:

Whereas, We have given March 7th as a dead line for our employers to comply with our demands, and whereas

We have instructed our committee that in the event our employers do not comply with our demands on said date, that within ten days they shall proceed to take a strike vote, and whereas

President Ryan has requested us to take no drastic action until the 22nd of March on which date we have been informed the Code will be signed, and whereas

He further requests us to forward our strike vote to him to use same in our behalf

Therefore, be it Resolved, that we instruct our Committee that in the event our employers do not comply with our demand by March 7, that they immediately take a strike vote of all Pacific Coast Locals, and

Be it further Resolved, that said strike vote be forwarded to our International President, to use in our behalf, and

Be it further Resolved, that we inform the International President that if our demands are not met by our employers on March 22nd a strike will be called in all Pacific Coast ports at 6a.m. on March 23rd.'

The resolution passed by a resounding voice vote of AYE and the convention adjourned. Up and down the West Coast, a referendum vote by the rank and file to strike carried by a huge majority, with only Anacortes voting against striking. As March 23 approached and there was no progress in negotiations, President Franklin D. Roosevelt requested the ILA Pacific Coast District Executive Board to delay the start of the strike.

Roosevelt promised to appoint a fact-finding commission to investigate the controversy and recommend a solution. The ILA Board complied with the President's request and waited. But the President's mediation panel could not find a workable compromise, and on May 9, 1934, 12,500 West Coast longshoremen went on strike. Moreover, this time longshoremen were supported by the seamen, engineers, masters, mates and pilots and other marine unions.

The maritime workers tied up their vessels when they reached port and struck as soon as meetings were convened to approve the strike. As coequal, but separate strikers, the seagoing men demanded higher wages, three instead of two watches, and employer recognition of their respective unions. Thus, the first industry-wide strike in shipping history began.

It was to be a memorable strike that eventually involved nearly 35,000 workers and lasted 83 days.

Immediately union spokesmen went to the press to explain their position to the general public. In Tacoma a committee was formed to carry out that task for the duration of the strike. Named the Tacoma Longshore Press Committee, it was led by Robert Hardin, Paddy Morris, Ernest Tanner and Tiny Thronson. Hoping to gain public support for their cause, this union committee sent the following letter to local newspapers and radio stations:

All we're asking for is a fair shake and if we get that we will be satisfied. We also wish to impress on the minds of the public that we don't like strikes, but we are forced to fight for what we believe are our just dues. We were informed there was to be a code under the National Recovery Act for the shipping industry and that our work would be covered ... The promised code was not forthcoming and there is still none today. A code, however, was given the shipowners and that gave them the edge over us right off the bat.

Then it was proposed by Dr Boris Stearns of the US. Department of Labor that the government supervise and operate the hiring of all longshoremen, and the elimination of our local booking offices in all ports. That was turned down at a convention of Northwest longshoremen held at Portland last winter In December, however, we were given 10 cents an hour raise in basic pay, making 85 cents. We were receiving 90 cents prior to 1931.

Then we were again assured that in the near future the promised code would be signed and the employers would be forced to meet us. On February 25, we held a convention in San Francisco and elected a committee of seven to meet San Francisco employers and shipowners. 7hey refused to recognize our committee as representing the ILA.

It was then that we, through our international president, issued the ultimatum setting March 23 as the time of the strike ... There was ... a telegram from President Roosevelt, who proposed he would find an impartial board. We complied with the President's request and the board was appointed and met with our executive board. The shipowners refused to take part in the conference at first, but were later persuaded by the President's board. They refused point blank to give us any consideration in regard to hours and wages, thus breaking the agreement they made with our organization and the President's board.

We feel that Tacoma Waterfront Employers will agree to our claim that through our work Tacoma has had far more efficiency and far fewer accidents in the loading of ships than at any other

port on the Coast.

Tacoma ILA. Statement Issued Thursday, Noon May 9,1934

Similar statements to newspapers and radio stations were made in all ports as the strike began. Recognition that public opinion was important indicated a growing sophistication by longshoremen in their struggles to beat the employers. No longer did longshoremen simply believe their cause was just and that the public would somehow understand their point of view.

The men now understood that it was necessary to explain repeatedly to the people the circumstances causing the strike and what the goals of the workers were. The general tenor of all longshore publicity during the twelve-week strike stressed that the stoppage was a struggle by workers to achieve job security through the closed shop and union hiring halls.

The West Coast maritime strike became front-page news nationally, and most editors and publishers sided with employers. Their editorials and feature articles repeated management's position that the strike was a Communist plot and longshoremen were being duped by radicals. The subject of Communist control of the ILA was brought up by the employers as early as the meeting between the convention negotiating committee and the waterfront owners before the strike. ILA District Secretary Bjorklund told the

bosses then,

... at Tacoma, these men in question [Communists] were hired by the employers and when trouble broke out they tried to lay the responsibility on us ... It was specifically stated in our Constitution that any man who belonged to a dual organization should be expelled from our organization. So they didn't get away with that. I finally told them that I had been jumped on from hell and back again by the employers and the communists, and that, personally, I was fed up on it.'

The greatest national attention was directed toward the strike in San Francisco. The Bay City was not only the headquarters of the largest ILA local, but also of other maritime unions and most of the shipowners. All maritime crafts became deeply involved in strike activities. There were daily parades on the Embarcadero to draw attention to the cause, and more importantly the joint Marine Strike Committee maintained a full complement of pickets at all San Francisco docks to keep out strikebreakers. Fully aware of the importance of San Francisco as the major testing ground, the ship- ping industry braced itself for another fight to the finish.

The Tacoma Longshoremen's "Flying Squad"

In the Pacific Northwest, strike activity took place mainly in Seattle, Portland and Everett, where police, armed guards, scabs and longshoremen fought sporadically on the docks and in nearby streets. Tacoma escaped most of the violence because Commencement Bay employers made few efforts to import scabs and force the docks open.

Perhaps the reason for the reluctance of the employers to break the picket lines was the formation of a special unit of Tacoma longshoremen called the Flying Squad. When the 1934 strike was only three days old, the Flying Squad participated in scab-clearing on the Seattle docks.

Altogether 600 Tacoma and 200 Everett longshoremen stormed the Seattle waterfront from Nelson Dock to the Bell Street Terminal driving scabs away from employer piers. Led by Henry Brown, Victor Olson, Fred Sellers and George Soule, the Tacoma Flying Squad spent much time in Seattle and other Washington State ports strengthening the ranks of their coworkers whenever employers threatened to open a port with scabs.

Although organized as an official union activity, even the Tacoma Strike Committee did not always know what the Squad was doing. Secrecy was considered essential to success, and staying out of jail.

Evidently, much planning had taken place by Tacoma longshoremen before the strike began. On March 30, 1934, Tacoma Locals 38-30 and 38-3 amalgamated into ILA Local 38-97, thereby ending the long-standing rivalry between lumber handlers and general cargo longshoremen. The merger of the two Tacoma locals clearly meant a united front toward employers. Moreover, the ever busy Paddy Morris was the Tacoma Central Labor Council President in 1934, and on the day the strike began the council passed a motion that if troops are used to break the Longshoremen's strike, the Council will call a general strike.

Washington State Governor Clarence Martin reacted to the Tacoma Central Labor Council announcement by calling a conference on May 16, 1934, which included the shipping employers, the ILA, the Council, State Federation of Labor, and the Teamsters. The meeting turned out to be a failure because employers urged the Governor to use the National Guard to open Washington ports.

The union representatives told Martin to keep his hands off or there would be a general strike from Bellingham to Portland, Oregon. After the meeting, Martin announced that he hoped the men would go back to work under a truce, pending the outcome of federal mediation efforts in San Francisco. Puget Sound longshoremen refused to consider his suggestion of a truce and continued to picket the docks.'

In the midst of the first hectic month, ILA President Joseph P. Ryan invited himself to the West Coast to settle the strike. On May 28, 1934, Ryan, en route to San Francisco, stopped in Tacoma and Seattle where he complimented the men for their magnificent fight. Pressured by the federal government mediation service, employers negotiated with Ryan and ILA Pacific Coast District representatives.

A proposed agreement on May 28, 1934, recognized the ILA, but failed to provide for a coastwide agreement, or the union hiring hall. The longshoremen rejected the proposal decisively when it was sent to the locals for ratification. In fact, the Ryan proposal outraged the Tacoma local. A spokesman for 38-97 told the Tacoma Daily Ledger:

We are right back where we started from. Hours, wages and working conditions we have stated our willingness to arbitrate, but the hiring hall is the vital issue. There can be no compromise with dishonor .

When 95 percent of the longshoremen on the Pacific Coast voted to go on strike, the issue of hiring halls and methods of dispatching the men was the paramount question. The proposition submitted back to us by the employers is not an offer It is an insult to the intelligence of the members.

There can be but one answer and that is absolutely no.'

Undaunted, Ryan entered negotiations again with the employers on June 16, but this time with the assistance of Dave Beck, president of the Seattle Teamsters, and Mike Casey, Beck's counterpart in San Francisco. Both Beck and Casey thought the maritime strike had lasted too long and the strikers should take what they could get from the employers.

Ryan emerged from his meeting with the employers with another settlement very similar to his May 28 agreement, but with a Beck and Casey guarantee binding Teamster unions to cross picket lines if any longshoremen failed to return to work under the provisions of the new settlement.'

Ryan then called upon the San Francisco local to ratify the agreement, but the Golden Gate City strikers turned him down. He immediately flew to Portland, Oregon, and met with the longshore-

men there. The men listened quietly and then shouted down his proposal. Ryan traveled to Tacoma, where he met with the joint Northwest Strike Committee. The ILA President pleaded with the committee to ratify his second settlement.

The strike committee listened politely, but like San Francisco and Portland strikers, the Northwesterners voted Ryan down without a single vote in favor. Walter Freer, chairman of the joint Northwest Strike Committee and also President of the Tacoma ILA local, reported to the press, No body of men can be expected to agree to self-destruction.

When the Teamsters failed to carry out their threat to cross longshore picket lines, and President Ryan declared he was taking a back seat in any further negotiations, the initiative passed to the Pacific Coast District ILA negotiating team of Cliff Thurston from Portland, Paddy Morris and jack Bjorklund of Tacoma, and William J Lewis of San Francisco. At the same time a membership referendum instructed the new team to add to the original demands of ILA recognition, closed shops and union hiring halls, a new proviso that employers must also reach satisfactory settlement with other maritime unions. The employers emphatically rejected the latest ILA Pacific Coast District proposal.

Historically, longshore and maritime strikers were organized in coastwide unions that determined basic strike policy and represented their members in dealing with the government and employers. However, it was understood that the membership of each union had the final say on proposals to and from the employers. In the day-today contest with the employers over all aspects of the 1934 strike, the striking maritime workers were united in joint strike committees in each port. The joint Northwest Strike Committee was composed of representatives of the striking unions in Puget Sound, other Washington ports and Portland.

As the strike continued, Seattle employers and newspapers agitated the public about the plight of starving Alaskans. The joint Northwest Strike Committee decided to release vessels to alleviate the distress. The ILA signed the Alaska Agreement with shipowners on June 8, providing for the closed shop, union hiring hall, the six-hour day and retroactive wages to be arbitrated. The employers also agreed to demands from the seagoing unions, and the vessels were loaded and sent to Alaska from Seattle.

Coinciding with the second round of negotiations between Ryan and the shipowners, the Mayor of Seattle, Charles L. Smith, and a newly formed Tacoma Citizen's Emergency Committee announced on June 15, 1934, a coordinated effort to open their ports by force, if necessary. Mayor Smith proclaimed an emergency and took over personal control of the police force. Then Smith announced he would guarantee police protection to anyone loading or discharging cargo in the Queen City

In Tacoma, the Chairman of the Citizen's Emergency Committee, John Prins, told the Daily Ledger on the same day, June 15, that we are prepared to open the port and afford our languishing industrial and business life some relief Three days later, on June 18, the Citizen's Emergency Committee followed up their first statement with an open letter to waterfront workers:

A MESSAGE TO THE 5000 WORKERS IN TACOMA WHO HAVE BEEN THROWN OUT OF WORK BY THE LONGSHOREMEN'S STRIKE THE PORT OF TACOMA WILL OPEN

This is a definite promise by the Tacoma Citizens Emergency Committee. You, who are eager to work, and have had the opportunity to work until interrupted by this strike, will have the opportunity again-the Port of Tacoma WILL OPEN.

Business was beginning to pick up in Tacoma. Mills and factories were re-opening. Thousands had been called back to their jobs. Then this strike. Factories, unable to receive raw materials and unable to deliver finished products, were compelled to close down.

600 TACOMA LONGSHOREMEN HAVE NO RIGHT NOR WILL THEY BE PERMITTED TO DICTATE THE FUTURE TO 106,000 PEOPLE"

While the Citizen's Emergency Committee was securing Tacoma City Council approval for assigning additional police officers to patrol the docks, Mayor Smith tried to reopen a Seattle pier on June 2 1. The result was a pitched battle at Smith Cove between strikers, scabs, police and armed guards. The police used tear gas and night sticks, and kept Smith Cove open.

The joint Northwest Strike Committee retaliated by suspending their special agreement exempting Alaska shipowners from the closure of the port. As a spokesman for the Strike Committee related to the press, the Alaska deal was based on an agreement that the Mayor and the city would assume a neutral attitude. Alaska Governor John W Troy quickly wired the joint Northwest Strike Committee to please cooperate, but the committee referred the Governor's request to the Seattle Mayor and the employers."

On June 22, the Tacoma Citizen's Emergency Committee decided to reopen the Port of Tacoma. A Tacoma policeman, who was sympathetic toward the strikers, alerted longshoremen that a Greyhound bus filled with scabs was coming from Seattle to Tacoma around 5 a.m. At that early hour the bus pulled up in front of the ILA hall at 14th and Pacific and the strikebreakers transferred to waiting trucks. Longshoremen at the hall did not challenge the scabs.

But down at the Milwaukee dock the Flying Squad and 400 Tacoma strikers were waiting for the strikebreakers. Retired longshoreman Victor Olson remembers that the Flying Squad nailed shut the dock gates so that scabs could not pass through to the piers. Olson also recalled that there was a parley beside the trucks between Tacoma longshoremen, the Seattle scabs, and the local police. The law officers disarmed the scabs of their pistols, blackjacks, tear gas cannisters and baseball bats.

The strikebreakers then climbed aboard the trucks and went back to Seattle. Many years later Olson declared, I'd do it again. I believe in the right to fight for my job.

As strike activity eased in Tacoma, the situation became more tense in Seattle. General strike talk similar to 1919 surfaced as Seattle strikers, aided by Tacoma's Flying Squad, continued to battle police and strikebreakers on the Queen City's waterfront.

The Seattle longshoremen sent a request to the Seattle Central Labor Council asking for a work stoppage by all union labor in the city. Tacoma, Longview, and Portland Central Labor Councils already had expressed their willingness to call a sympathy strike if National Guard troops were sent to the docks. However, in the Seattle Central Labor Council, the Teamsters successfully blocked a vote by the delegates to support longshoremen and marine workers, and general strike discussions died out.

While turmoil continued on the Seattle docks, the Tacoma Citizen's Emergency Committee tried to open the Port of Tacoma again. Chairman John Prins negotiated on June 25 a special agreement with port authorities to supply a berth for scab ships. But Prins' understanding with the Port Commissioners was short-lived when, quite mysteriously, the Port reneged on its promise. At the same time union pickets disappeared from the Port of Tacoma piers.

This action followed a closed-door meeting between the Port COmMiS- sioners and the joint Northwest Strike Committee. Though cha- grined, the Citizen's Emergency Committee claimed credit for the Port-longshore truce once it became public knowledge. Despite renewed attempts by Prins to reopen the port, there was no movement of ships into or out of the harbor.

On the same day the Emergency Committee's agreement with the Port of Tacoma failed, federal mediator Charles A. Reynolds told longshoremen and Alaska employers that a new agreement covering supplies for the Northern Territory must be reached soon or government troops would load chartered ships. Other public officials, as well as the newspapers, decried the longshore embargo of food and medicine for the Alaskans, and by July 3, public opin- ion was turning against the strikers.

On July 5, 1934, the joint Northwest Strike Committee agreed to load Alaskan ships in Tacoma under the terms of the first Alaska agreement. It was also understood that no effort would be made by employers to open Commencement Bay by force.

Concerned that its business would be lost to government-chartered ships, the Alaska Steamship Company acceded to the joint Northwest Strike Committee's demands. The Tacoma Port Commission then authorized use of its docks. On July 6 the first four Alaska steamers arrived at the Tacoma piers with union crews.

As a result of the joint Northwest Strike Committee's victory over Alaska shipowners, longshoremen from Pacific Northwest ports traveled to Tacoma, where they were dispatched from the union hall to work the ships. Half of the wages was paid directly to the men, one-fourth was sent to their local strike committee, and another fourth went to the joint Northwest Strike Committee. The committee sent $2,000 to the San Pedro strikers, $300 to San Francisco, and various amounts to other California locals.

The joint Northwest Strike Committee also set aside $1,500 to organize a coastwide maritime federation that would make permanent the solidarity of the longshoremen with the seagoing unions. Throughout the long strike, discussions took place between the ILA and the Masters, Mates and Pilots; Marine Engineerly, Sailors; Cooks and Stewards; Marine Firemen, and Radio Telegraphers about establishing a united organization for greater strength. By the end of the strike there was universal support for the idea of a federation among all maritime unions.

The End of the 1934 Strike

The lifting of the Alaska shipping embargo ended the Tacoma Citizen's Emergency Committee's campaign to force ihe Port of Tacoma open. The committee announced that the Seattle Waterfront Employers' Union would protect Tacoma's interest in the dispute with the longshoremen and the maritime workers. In turn, the WEU sent a representative to participate in hearings with the newly constituted National Longshoremen's Board (NLB) in San Francisco.

Labor legislation passed by Congress during June 1934 empowered the President to establish boards of investigation and arbitration in labor disputes. The NLB was the first created by Roosevelt under the new federal law. On June 26, President Roosevelt appointed

Archbishop Edward Hanna of San Francisco, Assistant Secretary of Labor Edward F McGrady, and San Francisco attorney Oscar K. Cushing to the NLB to bring the contesting sides together and settle the strike.

But by this time the positions of both the employers and the strikers had hardened to granite. At the NLB hearings longshoremen insisted on the union hiring hall, increased wages and better working conditions, as well as recognition of the marine unions. As expected, the employers adamantly rejected the longshore and marine unions' demands.

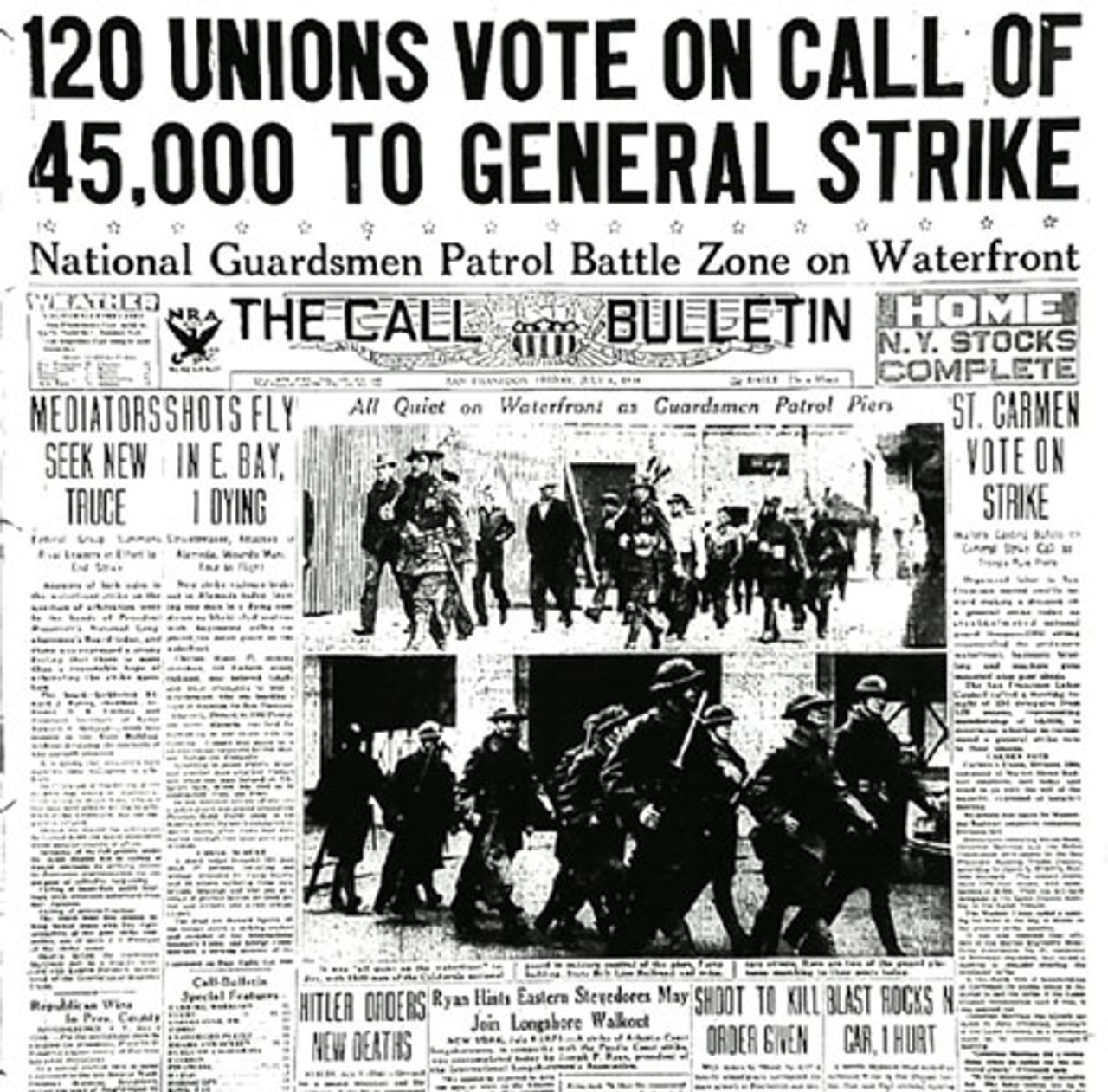

With the failure of the first effort by the NLB, the San Francisco employer group now determined to open the Embarcadero even if it took every available police officer in San Francisco. On July 3 employers' trucks rolled out of Pier 38 behind eight police patrol cars. Police Captain Thomas M. Hoertkorn, waving a revolver at pickets, yelled, The port is open!

The strikers surged forward and threw bricks, cobblestones and railroad spikes at the trucks. The police answered with night sticks, tear gas and bullets. The pickets retreated and merged with the crowd. July 4 was quiet, but on July 5, known as Bloody Thursday, one striker and a sympathizer were killed downtown and a mammoth confrontation took place on Rincon Hill. Here the strikers fought with bricks and stones, and the police hurled tear gas and used night sticks on strikers. Finally the battle was over and the police had won."

Within hours of the Rincon Hill battle, national guardsmen took positions along the San Francisco waterfront. The Golden Gate City was particularly tense on July 9 as thousands of longshoremen, other union men and women, and their sympathizers walked silently down Market Street in the funeral procession for the two men who had been killed. The long, solemn march awed many who saw it. The employer history of the strike credits this funeral procession with turning the tide of public opinion in favor of the strikers.

In response to affirmative votes by affiliated unions, the San Francisco Labor Council declared a general strike on July 15, 1934. It was a peaceful and effective strike that lasted three days. Though most of the California newspapers editorialized that the general strike was led by Communists, the general populace

remained sympathetic to the strikers.

On the second day of the general strike, the San Francisco Labor Council debated a resolution calling for arbitration of all out- standing issues between longshoremen and marine workers on the one side and employers on the other. Harry Bridges, Chairman of the San Francisco joint Marine Strike Committee, asked that the hiring hall issue not be included in the arbitration package. However, the Council voted 207 to 180 in favor of arbitrating all issues. On the next day, July 18, the National Longshoremen's Board reacted to the labor council's resolution by offering its services as arbitrator.

The labor council then went a step further and declared on July 19 that the general strike would end, upon acceptance by the shipowners and employers of the striking maritime workers, of the terms

of the President of the Longshoremens Board."

On July 20 the leaders of the waterfront employers and newspaper publishers held a private meeting in a San Francisco suburb. After the meeting, newspapers carried featured stories announcing that the employers would accept arbitration if the ILA also submitted all differences to the NLB.

Shipowners also agreed to elections on all vessels and to accept union recognition if a majority of the seamen voted for the union. Thus, on Saturday evening, July 21, every ILA local on the Pacific Coast voted on whether to submit their differences with the employers to the NLB. The rank and file voted in favor of arbitration 6504 to 1525 and went back to work the next week.

During October 1934, the National Longshoremen's Board announced its decision in the form of an Award. The NLB sought to effect a compromise on the most important issue, the hiring hall.

The hiring of all longshoremen shall be through halls maintained and e dispatcher shall be operated jointly, declared the Board, but

selected by the International Longshoremens Association. While on the surface this section of the Award appeared to be a compromise, in reality longshoremen had won a major victory. The dispatcher was the key to hiring, as owners and the ILA had learned from the 1917 NAC ruling. The government then had taken over the hiring halls and appointed union men as dispatchers with the end result that unions controlled who was sent to work on the docks."

The NLB also created a joint Labor Relations Committee of three employers and the same number of longshoremen to operate each hall. This committee was also required to maintain a list of registered longshoremen who would receive preferential employment over casuals. Grievances by either workers or employers were also resolved by the Labor Relations Committee. Additional ILA gains included wage increases to 95cts an hour straight time and $1.40 for overtime, a shorter week of thirty hours, and a sixhour day.

The longshoremen's allies in the 1934 strike also made significant gains. The marine union elections resulted in recognition and collective bargaining rights for the unions on most coastwise and offshore shipping lines. However, the unions were defeated in elections held on the tanker fleet. The men working for the oil companies voted to stay members of company unions.

Overall, the 1934 strike was a major victory for the marine and longshore unions. Not only had they won most of their demands, but the men had also gained a sense of power and solidarity during the strike that carried their unions to further victories in future negotiations.

Employers did not come away from the NLB Award emptyhanded.

Shipowners and dock managers gained the power to introduce labor saving devices and to institute such methods of discharging and loading cargo as they considered best for the conduct of their businesses. This was the first major Pacific Coast settlement that included a provision concerning mechanization. It was to be an increasingly important issue between longshoremen and owners as new machines began to replace men on the docks and in the ships' holds.", As far as Tacoma was concerned, Local 38-97 was exempted from the joint hiring hall provision mandated by the NLB Award. The Tacomans kept their hall under full union control with their own dispatcher, there by maintaining a pace-setting standard for the rest of the ILA.

The 1934 victory over the employers marked the apex of Tacoma influence in the affairs of Pacific Coast longshoremen. The work of Jack Bjorklund and Paddy Morris in organizing and consolidating the ILA membership into a bastion of labor strength unknown in previous eras had taken fifteen years. But signs of change within the ILA were on the horizon. Ambitious men like Harry Bridges were emerging on the waterfront.

Supported by the large San Francisco local and Communists, Bridges soon sought to wrest control of the ILA Pacific Coast District from the established leadership. It was to be a power struggle with immense consequences, especially for the Tacoma local.

1934 Longshore Strike

Jerry Lembcke, and William M. Tattam, "The 1934 Longshore Strike," One Union in Wood, a political history of the International Woodworkers of America. New York: Harcourt, 1984 p. 28-30.

Until 1934, a longshoreman's job security was tied to the paternalism of the work-crew foreman; whisky, money and other assorted favors guaranteed jobs. Men milled about outside company offices at early morning shape-ups until a signal from the boss indicated that they had been selected for the day's stevedoring.

Then, in May, 1934, the jurisdiction of the company unions which were maintained by the West Coast shippers was challenged by the International Longshoremen's Association, An. The Waterfront Employers'Association of San Francisco refused the iLA's demands for union recognition, a dollar an hour wage, a thirty-hour week and a unioncontrolled hiring hall.

Led by Harry Bridges in San Francisco, longshoremen retaliated by shutting down the waterfronts from San Diego to Seattle and pressing for a coast-wide working agreement.

From May 9 to July 31, 1934, docks along the Pacific Northwest were controlled by the striking longshoremen. Normal shipments of lumber and agricultural products were curtailed, and sawmills were forced to close when lumber could no tonger be shipped by water. By June, with no end in sight, 17,000 lumber workers were laid off and payrolls were slashed almost in half.

However, members of the National Lumber Workers Union solicited funds for the longshoremen and spoke in favor of the strike; as a result, lumber and sawmill workers supported the strike and did not scab despite their own desperate straits. Even the big mills at Longview, Washington ground to a halt when for four days, beginning June 19, 1934, sawmill workers there went out on strike in sympathy with the longshoremen .

On July 3, San Francisco businessmen announced that their trucks and drivers would move through the picket lines to the piers along the Embarcadero and remove the goods stranded there since the strike began. Longshoremen attacked the trucks with bricks, and police retaliated with clubs, tear gas and gunfire.

Two days later, on Bloody Thursday, the Battle of Rincon Hill left two longshoremen shot to death by the police, thirty wounded and forty-three more either clubbed, gassed or stoned. Four days later, 15,000 longshoremen and sympathizers marched up Market Street behind a flat-bed truck carrying the coffins of the slain longshoremen Union sympathies were now cemented, and on July 16 a three-day general strike began in San Francisco .

Anti-radical hysteria engendered by the general strike spread quickly. West Coast police departments sided unequivocally with the shippers and invested themselves with the kind of patriotic fervor reminiscent of the Palmer Raids of the early 1920s. On the first day of the San Francisco general strike, Portland police searched freight trains arriving from the south in an attempt to head off a feared invasion by "flying squadrons" of communist agitators; 130 men, mostly hoboes and migrant workers, were taken into custody.

Two reputed labor agitators, who supposedly planned to "radicalize" the local longshore strike by promoting a general strike, were also found on the train.

When local shipping companies demanded protection in order to continue loading ships along Portland's strike-bound waterfront, Oregon Governor Julius Meier ordered 1,000 National Guardsmen to mobilize immediately. Fortunately, the troops remained camped on the outskirts of the city after the Central Labor Council threatened to call an immediate general strike if the Guardsmen moved to the waterfront .

Between July 16 and 21, 1934, even though the San Francisco general strike had ended and the ILA had agreed to arbitration, the Portland police continued their searches and seizures. Private residences, Communist Party headquarters, and the Marine Workers Industrial Union hall were raided. Union records and Communist literature were seized and taken to the police station.

Three men were arrested for advocating criminal syndication, and thirty-two others were taken in for violations of the Oregon Criminal Syndication Act of 1919. All of those arrested were closely associated with the Communist Party and had worked with the Unemployed Councils to keep the unemployed from crossing the longshoremen's picket lines .

Dirk DeJonge, once the Communist Party's candidate for Mayor of Portland, was tried and sentenced on November 21, 1934 to seven years in prison. The charges brought against him included advocating violence during the longshore strike, being in possession of Communist Party literature, and conducting and attending Communist Party meetings.

After the Oregon Supreme Court upheld the conviction and Dirk DeJonge had spent nine months in the Oregon State penitentiary, the United States Supreme Court, on January 4, 1937, unanimously decided that the lower courts had erred in convicting him. The Court held "that the Oregon state law as applied to the particular charge as defined by the state court is repugnant to the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment".

The results of the 1934 longshore strike did not pass unnoticed by loggers and sawmill workers. The joint control of hiring halls with employers, the thirty-hour work week, wage increases and exclusive bargaining rights won by the longshoremen constituted notable union victories.

More importantly, however, the organization of the longshoremen meant that woodworkers had a strong ally for their own union activities. The two groups of workers were closely linked through family and occupational associations, while the Communist Party tied together the activists in both unions. If the woodworkers struck, it seemed a virtual certainty that the longshoremen would support them.

Jerry Lembcke, and William M. Tattam, "The 1934 Longshore Strike," One Union in Wood, a political history of the International Woodworkers of America. New York: Harcourt, 1984 p. 28-30.

Until 1934, a longshoreman's job security was tied to the paternalism of the work-crew foreman; whisky, money and other assorted favors guaranteed jobs. Men milled about outside company offices at early morning shape-ups until a signal from the boss indicated that they had been selected for the day's stevedoring.

Then, in May, 1934, the jurisdiction of the company unions which were maintained by the West Coast shippers was challenged by the International Longshoremen's Association, An. The Waterfront Employers'Association of San Francisco refused the iLA's demands for union recognition, a dollar an hour wage, a thirty-hour week and a unioncontrolled hiring hall.

Led by Harry Bridges in San Francisco, longshoremen retaliated by shutting down the waterfronts from San Diego to Seattle and pressing for a coast-wide working agreement.

From May 9 to July 31, 1934, docks along the Pacific Northwest were controlled by the striking longshoremen. Normal shipments of lumber and agricultural products were curtailed, and sawmills were forced to close when lumber could no tonger be shipped by water. By June, with no end in sight, 17,000 lumber workers were laid off and payrolls were slashed almost in half.

However, members of the National Lumber Workers Union solicited funds for the longshoremen and spoke in favor of the strike; as a result, lumber and sawmill workers supported the strike and did not scab despite their own desperate straits. Even the big mills at Longview, Washington ground to a halt when for four days, beginning June 19, 1934, sawmill workers there went out on strike in sympathy with the longshoremen .

On July 3, San Francisco businessmen announced that their trucks and drivers would move through the picket lines to the piers along the Embarcadero and remove the goods stranded there since the strike began. Longshoremen attacked the trucks with bricks, and police retaliated with clubs, tear gas and gunfire.

Two days later, on Bloody Thursday, the Battle of Rincon Hill left two longshoremen shot to death by the police, thirty wounded and forty-three more either clubbed, gassed or stoned. Four days later, 15,000 longshoremen and sympathizers marched up Market Street behind a flat-bed truck carrying the coffins of the slain longshoremen Union sympathies were now cemented, and on July 16 a three-day general strike began in San Francisco .

Anti-radical hysteria engendered by the general strike spread quickly. West Coast police departments sided unequivocally with the shippers and invested themselves with the kind of patriotic fervor reminiscent of the Palmer Raids of the early 1920s. On the first day of the San Francisco general strike, Portland police searched freight trains arriving from the south in an attempt to head off a feared invasion by "flying squadrons" of communist agitators; 130 men, mostly hoboes and migrant workers, were taken into custody.

Two reputed labor agitators, who supposedly planned to "radicalize" the local longshore strike by promoting a general strike, were also found on the train.

When local shipping companies demanded protection in order to continue loading ships along Portland's strike-bound waterfront, Oregon Governor Julius Meier ordered 1,000 National Guardsmen to mobilize immediately. Fortunately, the troops remained camped on the outskirts of the city after the Central Labor Council threatened to call an immediate general strike if the Guardsmen moved to the waterfront .

Between July 16 and 21, 1934, even though the San Francisco general strike had ended and the ILA had agreed to arbitration, the Portland police continued their searches and seizures. Private residences, Communist Party headquarters, and the Marine Workers Industrial Union hall were raided. Union records and Communist literature were seized and taken to the police station.

Three men were arrested for advocating criminal syndication, and thirty-two others were taken in for violations of the Oregon Criminal Syndication Act of 1919. All of those arrested were closely associated with the Communist Party and had worked with the Unemployed Councils to keep the unemployed from crossing the longshoremen's picket lines .

Dirk DeJonge, once the Communist Party's candidate for Mayor of Portland, was tried and sentenced on November 21, 1934 to seven years in prison. The charges brought against him included advocating violence during the longshore strike, being in possession of Communist Party literature, and conducting and attending Communist Party meetings.

After the Oregon Supreme Court upheld the conviction and Dirk DeJonge had spent nine months in the Oregon State penitentiary, the United States Supreme Court, on January 4, 1937, unanimously decided that the lower courts had erred in convicting him. The Court held "that the Oregon state law as applied to the particular charge as defined by the state court is repugnant to the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment".

The results of the 1934 longshore strike did not pass unnoticed by loggers and sawmill workers. The joint control of hiring halls with employers, the thirty-hour work week, wage increases and exclusive bargaining rights won by the longshoremen constituted notable union victories.

More importantly, however, the organization of the longshoremen meant that woodworkers had a strong ally for their own union activities. The two groups of workers were closely linked through family and occupational associations, while the Communist Party tied together the activists in both unions. If the woodworkers struck, it seemed a virtual certainty that the longshoremen would support them.

LONGSHOREMAN'S STRIKE OF 1934.

Gordon Newell, "The Longshoreman's Strike of 1934," H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1966, p. 428.

In June [1934] Mayor John Dore, an avowed friend of labor, retired as mayor of Seattle, and was replaced by Charles L. Smith a more conservative type. Perhaps recalling the nationwid; publicity which had accrued to Mayor Ole Hanson when he claimed to have broken the Seattle general strike of 1919, Mayor Smith prepared a compromise agreement which he submitted to the unions on a "take it or leave it" basis.

When the strikers decided to leave it he issued a proclamation that, as of June 21, Seattle was an open port, a move which had been successfully made at Los Angeles, with the result that former Puget Sound, Columbia River and San Francisco cargo was moving from that port, as well as from those of British Columbia.

The Seattle police chief soon afterward tendered his resignation and Mayor Smith took personal charge of the police. On June 21 a force of 250 policemen broke the picket line at the Smith Cove piers, mounted patrolmen leading the attack with swinging clubs. Non-union crews immediately began discharging cargo from the Donaldson Iiine European freighter Modavia and the Everett of the Tacoma Oriental Steamship Co. The unions immediately repicketed the Alaska vessels and the I. L. A. asked other Seattle unions to join a general strike in protest, a plan which was foiled by the refusal of Dave Beck, Northwest head of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, to cooperate.

Pickets displaced from Smith Cove transferred their activities to the employers' non - union hiring halls at the Smith Tower and Alaska Building, taking forthright measures to discourage prospective strikebreakers from entering. Within a week the unions agreed to permit Alaska sailings to be resumed, but only from Tacoma, and only upon the understanding that no effort would be made by governmental officials there to reopen the port to general shipping.

Violence was fast reaching its peak. At San Francisco a pitched battle between police, strikers and sympathizers resulted in 34 persons being shot, two fatally, and about 40 others gassed or badly beaten. Shots were fired by Portland police when 500 strikers attacked a locomotive attempting to move tank cars from the Union and Shell Oil Co. plants. A number of strikers were beaten by police clubs, a number of policemen seriously injured by rocks and bricks.

By mid July, vessels were still handling cargo at Smith Cove under heavy police guard, although picketers skirmished continually with guards, sometimes evading them and succeeding in beating up non-union longshoremen, ship's officers, or others observed violating the line. Steve Watson, one of the ,'special deputies" of the Citizens' Emergency Committee of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, was shot and killed in mob violence at 3rd and Seneca, in the heart of "uptown" Seattle. At this point the major issue remaining was the question of whether longshore hiring halls should be controlled entirely by the union or operated jointly by labor and management. President Roosevelt appointed an arbitration board to settle this issue and departed on a three-month vacation. It was finally agreed that the strike would be called off, pending arbitration of the remaining issues. All unions returned to work on August 1 but immediately walked out again on behalf of the maritime unions.

The truce agreement provided that all men employed after May 16 who had not previously followed the sea should be dismissed, but that men on the ships as of May 16 who had previously been employed at sea could be retained. The marine unions demanded that all personnel who had remained on the ships during the strike should be discharged.

The unions, after the brief walkout agreed that they had misinterpreted the agreement and work was resumed the following morning.

The position of the longshoremen's unions was strengthened in the 1934 strikes by their recognition, for the first time, as bargaining agents under the National Recovery Act (NRA). The maritime unions were not particularly effective during the 1934 strike, but as a result of the longshoremen's success (and NRA) they quickly became powerful in their own right.

The 84 -day period of economic stagnation and violence had ended, but its scars were a long time healing. The bitter ness of the .1934 strike was repeated during the next few years in a period of labor unrest such as has never been recorded in the history of the Pacific Northwest, before or since.

Foreign steamship operators were forced to route their vessels and cargoes via British Columbia ports during the long tie-up of American ports and some of them, having transferred their major Northwest functions north of the border, retained them there. Indicative of the tremendous advantage enjoyed by Canada during the strike is the lumber shipment barometer.

A total of only 2,748,920,847 feet was shipped from all Northwest ports. Washington exports total ed only 1,294,942,925 feet, a figure which Grays Harbor alone had approached during the boom years, and a decline of over a quarter of a billion feet over the depression figures of 1933.

Oregon shipments dropped to 594,513,208 feet, but British Columbia, a negligible factor in predepression figures, showed almost a 30% gain in 1934 over 1933, reaching a total of 859,464,714 feet, approaching the Washington figure and far exceeding that of Oregon. This was a trend which was to continue to the present time.

Gordon Newell, "The Longshoreman's Strike of 1934," H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1966, p. 428.

Gordon Newell, "The Longshoreman's Strike of 1934," H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1966, p. 428.

In June [1934] Mayor John Dore, an avowed friend of labor, retired as mayor of Seattle, and was replaced by Charles L. Smith a more conservative type. Perhaps recalling the nationwid; publicity which had accrued to Mayor Ole Hanson when he claimed to have broken the Seattle general strike of 1919, Mayor Smith prepared a compromise agreement which he submitted to the unions on a "take it or leave it" basis.

When the strikers decided to leave it he issued a proclamation that, as of June 21, Seattle was an open port, a move which had been successfully made at Los Angeles, with the result that former Puget Sound, Columbia River and San Francisco cargo was moving from that port, as well as from those of British Columbia.

The Seattle police chief soon afterward tendered his resignation and Mayor Smith took personal charge of the police. On June 21 a force of 250 policemen broke the picket line at the Smith Cove piers, mounted patrolmen leading the attack with swinging clubs. Non-union crews immediately began discharging cargo from the Donaldson Iiine European freighter Modavia and the Everett of the Tacoma Oriental Steamship Co. The unions immediately repicketed the Alaska vessels and the I. L. A. asked other Seattle unions to join a general strike in protest, a plan which was foiled by the refusal of Dave Beck, Northwest head of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, to cooperate.

Pickets displaced from Smith Cove transferred their activities to the employers' non - union hiring halls at the Smith Tower and Alaska Building, taking forthright measures to discourage prospective strikebreakers from entering. Within a week the unions agreed to permit Alaska sailings to be resumed, but only from Tacoma, and only upon the understanding that no effort would be made by governmental officials there to reopen the port to general shipping.

Violence was fast reaching its peak. At San Francisco a pitched battle between police, strikers and sympathizers resulted in 34 persons being shot, two fatally, and about 40 others gassed or badly beaten. Shots were fired by Portland police when 500 strikers attacked a locomotive attempting to move tank cars from the Union and Shell Oil Co. plants. A number of strikers were beaten by police clubs, a number of policemen seriously injured by rocks and bricks.

By mid July, vessels were still handling cargo at Smith Cove under heavy police guard, although picketers skirmished continually with guards, sometimes evading them and succeeding in beating up non-union longshoremen, ship's officers, or others observed violating the line. Steve Watson, one of the ,'special deputies" of the Citizens' Emergency Committee of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, was shot and killed in mob violence at 3rd and Seneca, in the heart of "uptown" Seattle. At this point the major issue remaining was the question of whether longshore hiring halls should be controlled entirely by the union or operated jointly by labor and management. President Roosevelt appointed an arbitration board to settle this issue and departed on a three-month vacation. It was finally agreed that the strike would be called off, pending arbitration of the remaining issues. All unions returned to work on August 1 but immediately walked out again on behalf of the maritime unions.

The truce agreement provided that all men employed after May 16 who had not previously followed the sea should be dismissed, but that men on the ships as of May 16 who had previously been employed at sea could be retained. The marine unions demanded that all personnel who had remained on the ships during the strike should be discharged.

The unions, after the brief walkout agreed that they had misinterpreted the agreement and work was resumed the following morning.

The position of the longshoremen's unions was strengthened in the 1934 strikes by their recognition, for the first time, as bargaining agents under the National Recovery Act (NRA). The maritime unions were not particularly effective during the 1934 strike, but as a result of the longshoremen's success (and NRA) they quickly became powerful in their own right.

The 84 -day period of economic stagnation and violence had ended, but its scars were a long time healing. The bitter ness of the .1934 strike was repeated during the next few years in a period of labor unrest such as has never been recorded in the history of the Pacific Northwest, before or since.

Foreign steamship operators were forced to route their vessels and cargoes via British Columbia ports during the long tie-up of American ports and some of them, having transferred their major Northwest functions north of the border, retained them there. Indicative of the tremendous advantage enjoyed by Canada during the strike is the lumber shipment barometer.

A total of only 2,748,920,847 feet was shipped from all Northwest ports. Washington exports total ed only 1,294,942,925 feet, a figure which Grays Harbor alone had approached during the boom years, and a decline of over a quarter of a billion feet over the depression figures of 1933.

Oregon shipments dropped to 594,513,208 feet, but British Columbia, a negligible factor in predepression figures, showed almost a 30% gain in 1934 over 1933, reaching a total of 859,464,714 feet, approaching the Washington figure and far exceeding that of Oregon. This was a trend which was to continue to the present time.

Gordon Newell, "The Longshoreman's Strike of 1934," H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1966, p. 428.