From

The Labor History Archives -In The 80th Anniversary Year Of The

Great San Francisco, Minneapolis And Toledo General Strikes- Lessons In The

History Of Class Struggle

75 years since the San Francisco general strike

By Marge Holland and Robert Louis

18 September 2009

On May 9, 1934, San Francisco longshoremen went out on strike against West Coast ship owners, igniting a movement of 35,000 maritime workers of the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) that shut down 2,000 miles of Pacific coastline from Bellingham, Washington, to San Diego, California.Driven by the determination and militancy of the rank and file, this 83-day struggle defied the employers’ Industrial Association of San Francisco, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s federal mediators, the conservative American Federation of Labor (AFL) union leadership, and culminated in the San Francisco general strike.

The San Francisco strike combined with two other momentous labor struggles in 1934 to alter the American political landscape—the Toledo Auto-Lite strike led by socialists in the American Workers Party, and the Minneapolis truck drivers strike led by Trotskyists in the Communist League of America. These three strikes—which were, in essence, rebellions not only against business interests but also against the business unionism of the AFL—paved the way for the pivotal victories of Detroit auto workers in sit-down strikes led by socialist-minded workers in 1937 and the formation of the mass industrial unions in the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations.)

Background to the strike

The events on the San Francisco waterfront in 1934 were the culmination of years of struggle by maritime workers against the ship owners and business interests grouped in the Industrial Association, which had been founded in 1921 to spearhead the anti-union, open-shop drive in San Francisco.For more than 14 years, the longshoremen (or stevedores) on the Pacific Coast had been separated by craft unions and individual port agreements. In San Francisco, a company hiring structure prevailed. For workers, this meant poverty wages, unsafe work and irregular employment.

In 1919, the US erupted in the largest strike wave to that point in its history, with nearly four million workers, or one-fifth of the nation’s labor force, walking off their jobs in the course of the year. One of the most electrifying of these struggles was the Seattle general strike of 1919, which proclaimed its solidarity with the Russian Revolution.

For five days, the city was virtually run by the General Strike Committee. In Seattle and San Francisco, dockworkers refused to handle weapons destined for the pro-capitalist and Czarist White Guard forces trying to crush the new workers state. [1]

San Francisco's dockworkers were then organized in the Riggers and Stevedores Association, a loose affiliate of the ILA. In 1919, longshoremen aimed to secure control over the work of loading and unloading. They struck against speed-up, which, combined with automation, made the pace of work unbearable. The men demanded lighter sling loads, an increase in the size of work gangs from twelve to sixteen men, and a share in company ownership.

The strike failed, as did another ILA-led struggle in 1921. A concerted offensive by the ship owners for the open shop followed. The owners formed a business union, the Waterfront Employers Union (WEA), which drove out the ILA and signed a “closed shop” contract, making itself the only union on the docks. It was officially called the Longshoremen’s Association of San Francisco and the Bay District, but to workers it was known as the “Blue Book” union for the color of its dues book.

After its triumph, the WEA signed a five-year agreement that featured a 10 percent wage cut. Speedup continued, and the notorious “shape up” system of casual on-site hiring was introduced. After 1919, only holders of the blue book could get jobs, and the WEA had the power to replace and blacklist workers. Although attempts were made in the 1920s to revive the ILA, the Blue Book dominated the lives of dockworkers for the next 14 years.[2][3]

In 1929, the AFL expelled the ILA-affiliated Riggers and Stevedores Association, in existence since 1853, and allowed the Blue Book “union” to enter the Labor Council.

Militant workers sought out different forms of organization. Among the veterans of the 1919 and 1921 strikes were members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), including the future leader of the San Francisco dockworkers, Harry Bridges. The IWW championed revolutionary industrial unionism in opposition to the corrupt AFL craft unions. After the strike defeats, the IWW was able to attract large numbers of seamen and longshoremen away from the AFL.

In April 1923, IWW workers organized in the Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union (MTW) called a general strike that received significant support among Pacific Coast marine, lumber and oil workers, as well as some construction workers. The principal demand was for the “release of class war prisoners,” coupled with separate economic demands for each industry. The IWW strike ultimately failed under the weight of court injunctions, mass arrests of strikers, and vigilantism by the Ku Klux Klan and the American Legion.[4]

By the early 1930s, two factions of the Communist Party began to carry out work among the longshoremen. The CPUSA had little success in an attempt to form an independent union, called the Marine Workers Industrial Union (MWIU.) The CPUSA was then in its ultra-left “Third Period.” Its unionization effort exhibited little interest in the actual conditions confronting workers, while it dismissed the AFL unions as “social fascist.”

In 1934, a group of Communists led by Sam Darcy took control of the CPUSA’s newspaper for longshoremen, the Waterfront Worker, making it a voice for industrial unionism. Bridges came under the influence of the CPUSA at this time, likely becoming a member.

The Great Depression was creating conditions favoring the growth of radicalism and militant struggle. According to a “Special Census of Unemployment” in January 1931, the number of unemployed workers in San Francisco increased from 24,467 in 1930 to 46,045 in 1931—a 47 percent increase in one year. From 1929 to 1930, expenditure for relief aid increased by 29.2 percent. However, by 1934 it had increased by 2,308 percent, and the number of families on relief increased 818 percent over 1929. [5]

More than 50 percent of all longshoremen were on the relief rolls. With irregular work, the vast majority of maritime workers were trying to live on an average subsistence wage of $10 a week. [6]

For longshoremen fortunate enough to have retained their jobs, the central grievance remained the “shape up.” At the crack of dawn, rain or shine, men hoping for work would assemble across from the piers on the Embarcadero and wait for the gang bosses to come out and announce how many men they needed and for how long. Sometimes the men would work a whole day, sometimes a few hours, sometimes as many as 24-36 hours straight.

Employment was intermittent, unpredictable and casual. The men were by turns out of work and forced to work long hours without a break. If they complained or got injured, they were fired. These conditions were compounded by bribery and discrimination. Workers who were known to have supported a union were blacklisted on the docks, while those who did favors or kept the gang bosses supplied with liquor were chosen for the best jobs. This condition was the norm up and down the West Coast.

Dock workers were, practically speaking, part-time, casual labor, with no guarantee of a regular wage. There were no regularly enforced safety standards and many men sustained serious, in some cases fatal, injuries.

The strike

In the second half of 1933, over 95 percent of San Francisco dockworkers joined the AFL’s newly revived ILA Local 38-79. This success was repeated up and down the Pacific Coast. However, ship owners refused to recognize the union or negotiate.In early March 1934, the ILA, under immense rank-and-file pressure, issued a demand that the shape up be abolished and replaced by a union-controlled hiring hall. If the demand was not accepted within two weeks, the San Francisco longshoremen would strike.

In response, the Blue Book WEA made a vague offer to cooperate with the ILA and open a dispatching hall under unspecified control. When the ILA leaders agreed with this proposal, the membership removed the local president for being “too conservative.” [7]

Frightened over the implications of a shutdown of West Coast shipping in the midst of the Depression, Roosevelt on March 23 succeeded in getting the ILA to agree to a strike postponement, which lasted six weeks. This delay gave the ship owners and their allies time to prepare.

Finally, on May 9, 1934, members of the ILA struck up and down the Pacific Coast. Within days, other maritime workers joined the strike. By the middle of May, some 35,000 waterfront workers were off the job, shutting down or limiting traffic at virtually all West Coast ports.

The workers’ central demand remained the union-controlled hiring hall, coupled with a closed shop and a Pacific Coast-wide bargaining agreement. Workers refused to place these issues in the hands of government arbitration. With their own hiring hall, the dockers felt they could achieve more steady, equal hours of work and significant control over the pace of work, which would mean fewer injuries and deaths.

Workers also demanded a six-hour day, a thirty-hour week, and $1 an hour in wages with overtime at $1.50.

To direct the strike, workers set up a Joint Marine Strike Committee composed of ten maritime unions. Harry Bridges, with the support of the CPUSA, was selected chairman. The strike committee insisted that no one would settle and return to work until the main demands of all the maritime crafts were met.

The employers, backed by federal, state and local officials, responded with a campaign of red-baiting and intimidation. They mobilized hundreds of police and thugs to attack the large picket lines. Hundreds of strikebreakers were housed aboard ships moored in the bay, but their usefulness was limited when truck drivers refused to move cargo.

Truck drivers offered critical assistance to the strikers in spite of the Teamsters Union leadership. When a delegation headed by Bridges endeavored to obtain Teamsters consent for bringing this most powerful union into the Joint Marine Strike Committee, Teamsters President Michael Casey refused to even consider it. [8] [9]

The longshoremen faced the behind-the-scenes resistance of their own union leadership. In mid-May, and again in June, the Roosevelt administration's labor mediator, Edward McGrady, concluded sellout deals with ILA national head Joseph Ryan. Both agreements left the issues of wages and hours dependent on arbitration and excluded the demands for a union-controlled hiring hall and closed shop, and a settlement that included all the crafts on strike. [10]

Ryan traveled to San Francisco from New York in an attempt to negotiate a capitulation to the employers independently of the strike committee and the rank and file. On June 16, Ryan and Casey met with the WEA “Blue Book” in Mayor Angelo Rossi’s office and arrived at an agreement that did not support any of the main demands except union recognition. Casey accepted this settlement and offered to resume the movement of cargo from the docks, telling reporters, “Our men will return to work Monday morning [June 18], regardless of what action is taken by the longshoremen at their Sunday meeting.” [11]

Ryan tried to get some of the ports to settle separately. But when he presented his deal to general meetings in the main ports, it was unanimously repudiated. At the San Francisco ratification meeting there was a loud rejection of the agreement and Ryan was booed off the platform. He left town denouncing the workers, declaring, “The [International] Longshoreman’s Association is dominated by the radical elements and Communists… .” [12]

At the end of June, the employers, with tens of millions of dollars of goods piled up on the piers, decided to open the ports by other means.

Bloody Thursday

Policeman attacks worker during the strike.

Policeman attacks worker during the strike. July 1934: Police use tear gas as strikers battle police on the Embarcadero. (Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library)

July 1934: Police use tear gas as strikers battle police on the Embarcadero. (Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library)  Two strikers shot by police. Charles Olson on left survived, Howard Sperry, on the right, died.

Two strikers shot by police. Charles Olson on left survived, Howard Sperry, on the right, died.The funeral march for Howard S. Sperry and Nicholas Bordoise on July 9 was a powerful expression of grief and outrage. As many as 40,000 people marched in respectful silence from the Ferry Building to Valencia Street, a distance of over two miles. Eight abreast, the working men walked slowly, hats off, to Beethoven’s “Funeral March.” They were joined by women and children and the families of the slain.

The killings, and the solemn dignity of the longshoremen’s mourning, created a wave of sympathy for the strikers. It was this, more than anything, that moved the working people of San Francisco to support a general strike.

Silent funeral march of 40,000 for slain workers Howard Sperry and Nick Bordoise.

Silent funeral march of 40,000 for slain workers Howard Sperry and Nick Bordoise.The general strike

After the police brutality of Bloody Thursday, the Joint Marine Strike Committee called for a general strike and scores of Bay Area union members voted their support against the wishes of the AFL leadership. At a mass meeting July 12, “Teamsters sang, ‘We’ll hang [Teamsters President] Michael Casey from a sour apple tree,’ and shouted him down when he argued passionately against a strike.” [15]Sympathy for the strikers was not limited to San Francisco or the West Coast alone. In New York City there was a call for a mass meeting in support of the San Francisco strikers. In Los Angeles every union in the city came out in support of the maritime workers and assessed their members 25 cents each to assist the strikers. The proprietor of a lunch counter declared, “Any of my help don’t walk out, I’ll kick their behinds out the door. That’s where I stand.” [16]

The labor officials, however, did not share this popular feeling.

On July 6, Labor Council President Vandeleur appointed a Strike Strategy Committee of seven—all right-wing bureaucrats headed by himself. The committee excluded all of the striking maritime unions in an attempt to wrest control of the movement from the rank-and-file-dominated ILA. As a maneuver to provide a democratic cover for its hidden agenda, it also formed a General Strike Committee of 50 that included Bridges, but which had no ultimate decision-making power.

The New York Times recognized the essence of the Strike Strategy Committee, headlining its article the next day, “General Walkout Blocked.” In response, Bridges now openly defended the reactionary AFL heads, saying in the next day’s ILA Strike Bulletin, “The Labor Council is definitely behind the marine strike.”[17]

By agreeing that the longshoremen’s Joint Strike Committee would be excluded from the leadership of the mass strike, Bridges effectively turned its control over to the AFL leadership. Months later, James P. Cannon, the leader and founder of the Trotskyist movement in the United States, noted that the general strike had fallen “into the hands of the reactionary officialdom,” who “transformed it into a weapon against the marine workers and against the ‘Reds,’” and then “deliberately broke the general strike and pulled the marine strike down with it.” [18]

Nonetheless, the labor bureaucrats could not hold back the general strike, resisting it “until the momentum of events threatened to overwhelm them.” [19]

National Guard tanks on the waterfront (Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library)

National Guard tanks on the waterfront (Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library)Meanwhile, 4,500 heavily armed National Guard troops were deployed throughout the city. Big business, the newspapers and government officials condemned the longshoremen as dangerous radicals and advocates of violence. National Recovery Administration (NRA) chief, General Hugh Johnson, declared the strike “a bloody insurrection” and called on “responsible” labor organizations to “run these subversive influences out from its ranks like rats.” [20]

National Guard machine gun nest (Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library)

National Guard machine gun nest (Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library)The Hearst propaganda machine failed to convince the workers. According to author Bruce Nelson, “the growing trend in the ranks was to view red-baiting as another in the arsenal of weapons that the employer used to divide and conquer the workers.” [22]

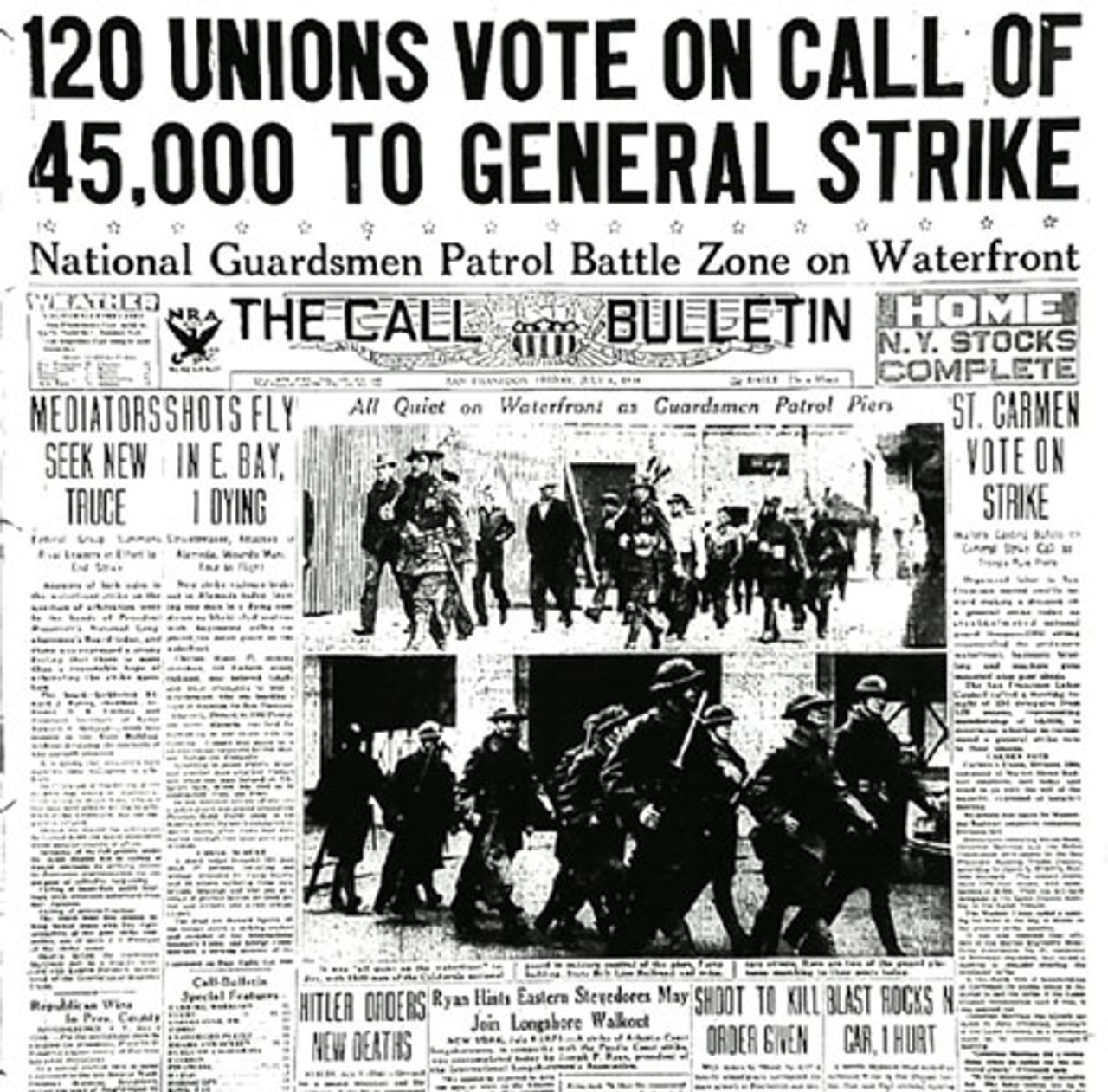

July 15, 1934: General Strike Headline, The San Francisco News Call Bulletin

July 15, 1934: General Strike Headline, The San Francisco News Call BulletinThe most effective weapon against the city’s workers proved to be the AFL-dominated Strike Strategy Committee, which was working behind the scenes to shut the strike down. On July 18 it voted to end the general strike, calling for all the demands to be submitted to federal arbitration.

The next day the Teamsters, after having been threatened by the city government with mass strike-breaking and firings, voted to return to work, further isolating the longshoremen. On July 31, longshoremen ended their strike, submitting the hiring hall demand to arbitration and returning to work without any of the demands of the seamen and other unions having been met.

Aftermath of the strike

In arbitration, the longshoremen won some of their main demands, gaining union recognition and a coast-wide agreement, a 12-percent wage increase from 85 to 95 cents per hour and overtime at $1.45. The workers also acquired a six-hour day at 30 hours per week, with job security and a regular, equal share of the work. The Blue Book company union and the shape-up were abolished.The National Labor Board federal arbitration committee granted the employers the right to continue work speed-up and mechanization to increase profits and compensate for the wage increase. On the key issue of hiring, longshoremen did not win their demand for a strictly union-controlled hiring hall and a closed shop. The hall was to be controlled by a Labor Relations Committee composed of both sides.

However, the settlement ruled that the dispatcher would be an ILA union member, and hiring would generally be determined by a list of registered longshoremen who had been regularly working for at least one year of the last three before the strike began. Union members had preference for hiring over non-union members. Strikebreakers were to be laid off.

Ultimately, the Roosevelt administration concluded it was better to give longshoremen substantial concessions than risk another confrontation at vital West Coast ports.

Yet the subordination of the general strike to the leadership of the AFL, which was supported by Bridges and the local ILA leadership, limited the strike’s effectiveness. Seamen and other unions in the Joint Strike Committee won little besides union recognition. And the strike left intact the power of the ship owners and West Coast business interests.

Later, in 1937, the dockworkers formally seceded from the AFL and joined the newly formed CIO, taking the name International Longshoremen and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU). In 1950, during the Red Scare, the CIO executive board expelled the entire ILWU from the labor federation, accusing its leadership, particularly Bridges, of being communist. Bridges always denied he was a Communist Party member, although recent archival research in Russia appears to prove that he was.

Like the Toledo Auto-Lite strike and the Minneapolis truck drivers strike, the West Coast longshoremen’s strike was a crucial experience for the working class. These militant struggles provided an impetus for the formation of the mass industrial unions. All three strikes represented a rebellion by workers, under socialist or radical leadership, against the craft union dominated AFL.

Yet ultimately the mass struggles of 1934 and after—which often took on insurrectionary dimensions—were defused by the trade union bureaucracy, the new CIO leadership included, and delivered politically to the Democratic Party.

As in the 1930s, workers today face the necessity of building new organizations. The existing trade unions are integrated into the structure of corporate management and the state, and work to lower the living standards of the working class in the name of competitiveness. Over the past several decades they have worked to hand back all the gains won by workers since the 1930s.

Workers must, and will, fight back, just as they did in 1934. The central lesson of the struggles of the 1930s is the necessity to articulate the independent political interests of the working class. To do so requires the building of an international mass socialist party with deep roots in the working class.

Notes:

1. Joshua Freeman et al., Who Built America?: Working People and the Nation’s Economy, Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 2, ed. Stephen Brier (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992), pp. 258-261.

2. Howard Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets?: The Making of Radical and Conservative Unions on the Waterfront (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), pp. 35-36

3. David F. Selvin, A Terrible Anger: The 1934 Waterfront and General Strikes in San Francisco (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1996).

4. Bruce Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront: Seamen, Longshoremen, and Unionism in the 1930s (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), p. 61-62.

5. Huntington, Emily H. Unemployment Relief and the Unemployed in San Francisco Bay Region 1929-1934, Heller Committee for Research in Social Economics, (Berkeley, CA: UC Press, 1939), p. 6.

6. “Longshore Labor Conditions and Port Decasualization in the United States,” Monthly Labor Review, December, 1933, quoted in Samuel Yellen, American Labor Struggles (New York: Monad Press, 1974), p. 328.

7. Jeremy Brecher, Strike (San Francisco: Straight Arrow Books, 1972), pp. 150-151.

8. Samuel Yellen, American Labor Struggles (New York: Monad Press, 1974), p. 333.

9. Paul Eliel, The Waterfront and General Strikes San Francisco, 1934: A Brief History. (San Francisco: Hooper Printing Company, 1934), p. 87.

10. S.F. Examiner, June 17, 1934, quoted in Eliel, p. 24.

11. S.F. Examiner, June 17, 1934, quoted in Eliel, pp. 70, 74.

12. Kevin Starr, Endangered Dreams, The Great Depression in California (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 101.

13. Brecher, p. 153.

14. Tillie Olson, Partisan Review, October 1934.

15. Bernstein, Turbulent Years, p. 280, quoted in Brecher, p. 154.

16. Mike Quin, The Big Strike (Olema, California: Olema Publishing Company, 1949), p. 118.

17. Selvin, p. 156.

18. James P. Cannon, “The Strike Wave and the Left Wing,” New International, Vol.1, No.3 September-October 1934, pp. 67-68.

19. Nelson, p. 149.

20. Sidney Lens, The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sitdowns (New York: Doubleday Anchor Press, 1973), p. 300.

21. Yellen, p. 347.

22. Nelson, pp. 145-146.

23. Art Preis, Labor’s Giant Step (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1972), 32.

No comments:

Post a Comment