Bradley Manning’s speedy trial motion denied, despite nearly three years without trial

In a pretrial hearing at Fort Meade, MD, Judge Denise Lind denied the defense’s motion to dismiss charges for lack of a speedy trial. She listened to arguments over government evidence, a written statement from Bradley, and an updated plea offer. Bradley will get a chance to explain his releases to WikiLeaks in a public discussion with the judge on Thursday.

By Nathan Fuller, Bradley Manning Support Network. February 26, 2013.

On PFC Bradley Manning’s 1,005th day in prison without trial, military judge Denise Lind ruled that the government has not deprived him of his due process right to a speedy trial. Rules for court martial require the military to arraign defendants within 120 days, and more than 600 passed before prosecutors arraigned Bradley. Judge Lind denied the defense motion to dismiss charges, ruling that the delays excluded by the Convening Authority were justifiably removed from the speedy trial clock.

On PFC Bradley Manning’s 1,005th day in prison without trial, military judge Denise Lind ruled that the government has not deprived him of his due process right to a speedy trial. Rules for court martial require the military to arraign defendants within 120 days, and more than 600 passed before prosecutors arraigned Bradley. Judge Lind denied the defense motion to dismiss charges, ruling that the delays excluded by the Convening Authority were justifiably removed from the speedy trial clock.

Judge Lind repeatedly referenced the “complexity” of the case and the “voluminous” set of documents at issue. She did say that prosecutors mishandled discovery documents and were not justified in delaying 6 days from the speedy trial clock shortly following the Article 32 pretrial hearing in December 2011. However, those caveats didn’t outweigh her decision that the government was otherwise largely diligent.

The ruling, a verbose litany of dates, delays, and correspondence, took more than two hours to read and was virtually impossible to transcribe in full. Judge Lind refuses to make her rulings, or any filings or transcripts for that matter, publicly available, so reporters are left to scramble and summarize.

Defense, Judge Lind question government’s prejudicial evidence

Judge Lind then questioned the prejudicial nature of the government’s request to submit evidence allegedly retrieved at Osama bin Laden’s raided compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Prosecutors said they want to prove that the United States’ enemy “received” documents that Bradley’s accused of releasing. But defense lawyer David Coombs said that the government could show evidence from anyone to prove that the documents were in fact published on the Internet, and that this move is intended to incur prejudice against Bradley, either from a potential jury or in the court of public opinion. Prosecutors have chosen bin Laden, Coombs implied, to impugn Bradley’s character in connecting him to America’s enemies.

Furthermore, Coombs said that this request contradicts the government’s previous contention that events after the fact – such as the lack of damage done to national security – are irrelevant to whether Bradley committed the offense. The defense is not allowed to show that WikiLeaks’ releases brought no harm to the U.S. on the grounds that later harm isn’t relevant.

Bradley Manning to make his case on Thursday

Finally, the defense has submitted a written statement explaining Bradley’s offer to plead guilty to several lesser-included offenses and not guilty to some of the major specifications. Bradley is expected to proffer to plead guilty to lesser offenses, such as “unauthorized possession” of documents instead of “exceeds authorized access,” that would carry a maximum of 20 years in jail. The plea offer triggers an in-session colloquy between Bradley and Judge Lind, currently scheduled for Thursday, in which she’ll ask him a series of questions to ensure he understands to what he’s pleading. Bradley submitted the supplemental statement, which is at least 25 pages long, to educate Judge Lind ahead of the discussion.

The government objected to the statement, claiming many of the personal and political factors Bradley wishes to discuss are irrelevant to the charged offenses. By way of these objections, we learned that included in the statement are some of Bradley’s explanations and feelings about WikiLeaks’ releases. For instance, he wrote to Judge Lind that he’d hoped the release of the Iraq War Logs would ‘spark a domestic debate on the role of our military and foreign policy in general.’

The statement also alludes to the seminal incident in the Army in which Bradley objected to Iraqi Federal Police detaining political dissidents for distributing literature. As he told Adrian Lamo in chat logs published by Wired, Bradley reported the repressive arrests to his superiors but was told to keep quiet and continue helping Iraqi police. This stonewalling, it was implied, led Bradley to look for alternative outlets to expose this abuse.

By Nathan Fuller, Bradley Manning Support Network. February 26, 2013.

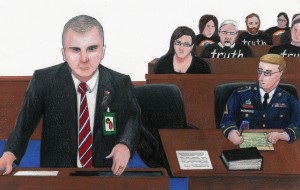

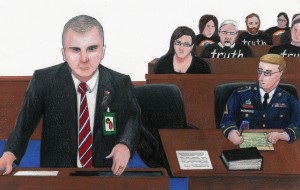

Defense lawyer David Coombs and PFC Bradley Manning, sketched by Clark Stoeckley of the Bradley Manning Support Network.

Judge Lind repeatedly referenced the “complexity” of the case and the “voluminous” set of documents at issue. She did say that prosecutors mishandled discovery documents and were not justified in delaying 6 days from the speedy trial clock shortly following the Article 32 pretrial hearing in December 2011. However, those caveats didn’t outweigh her decision that the government was otherwise largely diligent.

The ruling, a verbose litany of dates, delays, and correspondence, took more than two hours to read and was virtually impossible to transcribe in full. Judge Lind refuses to make her rulings, or any filings or transcripts for that matter, publicly available, so reporters are left to scramble and summarize.

Defense, Judge Lind question government’s prejudicial evidence

Judge Lind then questioned the prejudicial nature of the government’s request to submit evidence allegedly retrieved at Osama bin Laden’s raided compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Prosecutors said they want to prove that the United States’ enemy “received” documents that Bradley’s accused of releasing. But defense lawyer David Coombs said that the government could show evidence from anyone to prove that the documents were in fact published on the Internet, and that this move is intended to incur prejudice against Bradley, either from a potential jury or in the court of public opinion. Prosecutors have chosen bin Laden, Coombs implied, to impugn Bradley’s character in connecting him to America’s enemies.

Furthermore, Coombs said that this request contradicts the government’s previous contention that events after the fact – such as the lack of damage done to national security – are irrelevant to whether Bradley committed the offense. The defense is not allowed to show that WikiLeaks’ releases brought no harm to the U.S. on the grounds that later harm isn’t relevant.

Bradley Manning to make his case on Thursday

Finally, the defense has submitted a written statement explaining Bradley’s offer to plead guilty to several lesser-included offenses and not guilty to some of the major specifications. Bradley is expected to proffer to plead guilty to lesser offenses, such as “unauthorized possession” of documents instead of “exceeds authorized access,” that would carry a maximum of 20 years in jail. The plea offer triggers an in-session colloquy between Bradley and Judge Lind, currently scheduled for Thursday, in which she’ll ask him a series of questions to ensure he understands to what he’s pleading. Bradley submitted the supplemental statement, which is at least 25 pages long, to educate Judge Lind ahead of the discussion.

The government objected to the statement, claiming many of the personal and political factors Bradley wishes to discuss are irrelevant to the charged offenses. By way of these objections, we learned that included in the statement are some of Bradley’s explanations and feelings about WikiLeaks’ releases. For instance, he wrote to Judge Lind that he’d hoped the release of the Iraq War Logs would ‘spark a domestic debate on the role of our military and foreign policy in general.’

The statement also alludes to the seminal incident in the Army in which Bradley objected to Iraqi Federal Police detaining political dissidents for distributing literature. As he told Adrian Lamo in chat logs published by Wired, Bradley reported the repressive arrests to his superiors but was told to keep quiet and continue helping Iraqi police. This stonewalling, it was implied, led Bradley to look for alternative outlets to expose this abuse.

No comments:

Post a Comment