As The 100th Anniversary Of The First Year Of World War I (Remember The War To End All Wars) Continues ... Some Remembrances-Writers’ Corner

In say 1912, 1913, hell, even the beginning of 1914, the first few months anyway, before the war clouds got a full head of steam in the summer they all profusely professed their unmitigated horror at the thought of war, thought of the old way of doing business in the world. Yes the artists of every school but the Cubist/Fauvists/Futurists and Surrealists or those who would come to speak for those movements, those who saw the disjointedness of modern industrial society and put the pieces to paint, sculptors who put twisted pieces of metal juxtaposed to each other saw that building a mighty machine from which you had to run created many problems; writers of serious history books proving that, according to their Whiggish theory of progress, humankind had moved beyond war as an instrument of policy and the diplomats and high and mighty would put the brakes on in time, not realizing that they were all squabbling cousins; writers of serious and not so serious novels drenched in platitudes and hidden gabezo love affairs put paid to that notion in their sweet nothing words that man and woman had too much to do, too much sex to harness to denigrate themselves by crying the warrior’s cry and by having half-virgin, neat trick, maidens strewing flowers on the bloodlust streets; musicians whose muse spoke of delicate tempos and sweet muted violin concertos, not the stress and strife of the tattoos of war marches with their tinny conceits; and poets, ah, those constricted poets who bleed the moon of its amber swearing, swearing on a stack of seven sealed bibles, that they would go to the hells before touching the hair of another man. They all professed loudly (and those few who did not profess, could not profess because they were happily getting their blood rising, kept their own consul until the summer), that come the war drums they would resist the siren call, would stick to their Whiggish, Futurist, Constructionist, Cubist worlds and blast the war-makers to hell in quotes, words, chords, clanged metal, and pretty pastels. They would stay the course.

And then the war drums intensified, the people, their clients, patrons and buyers, cried out their lusts and they, they made of ordinary human clay as it turned out, poets, artists, sculptors, writers, serious and not, musicians went to the trenches to die deathless deaths in their thousands for, well, for humankind, of course, their always fate ….

| "Leave it—under the oak." | David Jones (1895-1974) |

Not counting the week-long preparatory bombardment, and the enormous mines that were set off under the German lines 10 minutes before the assault proper, the Battle of the Somme began precisely at 7:30am on a beautiful, sunny July 1st, 1916. At that moment the British troops crawled out of their trenches, and formed into orderly ranks to march across "No-Man's Land" and occupy the deserted German trenches (the artillery bombardment would have cut the barbed wire and killed the defenders). One Captain Nevill had given each of his platoons a soccer ball to kick-off as the attack began. It would be a grand "walk-over." That was the plan. In reality, men were killed instantly before they could even climb out of their trenches, Captain Nevill was one of them. The air was filled with flying metal. The Germans had survived the preparatory bombardment, and were manning their machine guns and artillery. Wave after wave of British soldiers were slaughtered, mowed down as they bunched up against the uncut wire. On that first day of the battle (which — it's almost impossible to imagine — would go on for four months) the British Army suffered almost 60,000 casualties, over 20,000 dead. A record.

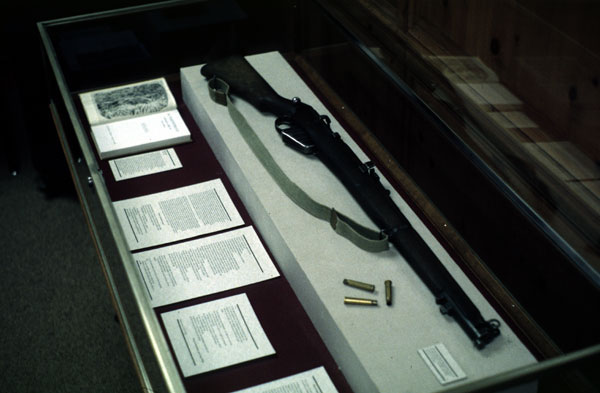

Not counting the week-long preparatory bombardment, and the enormous mines that were set off under the German lines 10 minutes before the assault proper, the Battle of the Somme began precisely at 7:30am on a beautiful, sunny July 1st, 1916. At that moment the British troops crawled out of their trenches, and formed into orderly ranks to march across "No-Man's Land" and occupy the deserted German trenches (the artillery bombardment would have cut the barbed wire and killed the defenders). One Captain Nevill had given each of his platoons a soccer ball to kick-off as the attack began. It would be a grand "walk-over." That was the plan. In reality, men were killed instantly before they could even climb out of their trenches, Captain Nevill was one of them. The air was filled with flying metal. The Germans had survived the preparatory bombardment, and were manning their machine guns and artillery. Wave after wave of British soldiers were slaughtered, mowed down as they bunched up against the uncut wire. On that first day of the battle (which — it's almost impossible to imagine — would go on for four months) the British Army suffered almost 60,000 casualties, over 20,000 dead. A record. In the climax of David Jones' epic prose-poem In Parenthesis, the protagonist John Ball attacks Mametz Wood, along with his unit, on the morning of the first day of the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916. As he goes forward, he watches as most of his fellows around him are ripped apart, but Ball somehow makes it through unscathed until that evening. When ordered to take part in a subsequent, follow-up attack, Ball is knocked down, hit in the legs by machinegun fire, and begins his long crawl back. Along the way he discards most of his equipment (except for his gas mask, which he thinks might come in handy). However, his rifle has special meaning: as any soldier knows, a warrior and his weapon are one: it defines who he is, lose it and he loses his identity. As he retreats, Ball carries on a conversation with himself: should he leave the rifle? He hears the voices of his drill instructors driving home the importance of care of arms, the individuality of each soldier's weapon, the intimacy that he should share with it. In Chanson de Roland, mortally wounded Roland tries to break his sword Durendal against a stone, but cannot, so instead tucks it under his body and dies. So at last, John Ball relinquishes the symbol of his soldierly identity, his rifle, and must "leave it—under the oak."

In the climax of David Jones' epic prose-poem In Parenthesis, the protagonist John Ball attacks Mametz Wood, along with his unit, on the morning of the first day of the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916. As he goes forward, he watches as most of his fellows around him are ripped apart, but Ball somehow makes it through unscathed until that evening. When ordered to take part in a subsequent, follow-up attack, Ball is knocked down, hit in the legs by machinegun fire, and begins his long crawl back. Along the way he discards most of his equipment (except for his gas mask, which he thinks might come in handy). However, his rifle has special meaning: as any soldier knows, a warrior and his weapon are one: it defines who he is, lose it and he loses his identity. As he retreats, Ball carries on a conversation with himself: should he leave the rifle? He hears the voices of his drill instructors driving home the importance of care of arms, the individuality of each soldier's weapon, the intimacy that he should share with it. In Chanson de Roland, mortally wounded Roland tries to break his sword Durendal against a stone, but cannot, so instead tucks it under his body and dies. So at last, John Ball relinquishes the symbol of his soldierly identity, his rifle, and must "leave it—under the oak." | From In Parenthesis, part 7 And to Private Ball it came as if a rigid beam of great weight flailed about his calves, caught from behind by ballista-baulk let fly or aft-beam slewed to clout gunnel-walker below below below. When golden vanities make about, you've got no legs to stand on. He thought it disproportionate in its violence considering the fragility of us. The warm fluid percolates between his toes and his left boot fills, as when you tread in a puddle--he crawled away in the opposite direction. It's difficult with the weight of the rifle. Leave it--under the oak. Leave it for a salvage-bloke let it lie bruised for a monument dispense the authenticated fragments to the faithful. It's the thunder-besom for us it's the bright bough borne it's the tensioned yew for a Genoese jammed arbalest and a scarlet square for a mounted mareschal, it's that county-mob back to back. Majuba mountain and Mons Cherubim and spreaded mats for Sydney Street East, and come to Bisley for a Silver Dish. It's R.SM. O'Grady says, it's the soldier's best friend if you care for the working parts and let us be 'av- ing those springs released smartly in Company billets on wet forenoons and clickerty-click and one up the spout and you men must really cultivate the habit of treating this weapon with the very greatest care and there should be a healthy rivalry among you--it should be a matter of very proper pride and Marry it man! Marry it! Cherish her, she's your very own. Coax it man coax it--it's delicately and ingeniously made --it's an instrument of precision--it costs us tax-payers, money-I want you men to remember that. Fondle it like a granny--talk to it--consider it as you would a friendöand when you ground these arms she's not a rooky's gas-pipe for greenhorns to tarnish. You've known her hot and cold. You would choose her from among many. You know her by her bias, and by her exact error at 300, and by the deep scar at the small, by the fair flaw in the grain, above the lower sling-swivel-- but leave it under the oak. Slung so, it swings its full weight, With you going blindly on all paws, it slews its whole length, to hang at your bowed neck like the Mariner's white oblation. You drag past the four bright stones at the turn of Wood Support. It is not to be broken on the brown stone under the gracious tree. It is not to be hidden under your failing body. Slung so, it troubles your painful crawling like a fugitive's irons. * * * At the gate of the wood you try a last adjustment, but slung so, it's an impediment, it's of detriment to your hopes, you had best be rid of it--the sagging webbing and all and what's left of your two fifty--but it were wise to hold on to your mask. You're clumsy in your feebleness, you implicate your tin-hat rim with the slack sling of it. Let it lie for the dews to rust it, or ought you to decently cover the working parts. Its dark barrel, where you leave it under the oak, reflects the solemn star that rises urgently from Cliff Trench. It's a beautiful doll for us it's the Last Reputable Arm. But leave it--under the oak. Leave it for a Cook's tourist to the Devastated Areas and crawl as far as you can and wait for the bearers. From In Parenthesis, part 7, pp. 183-86. David Jones (1895-1974) |

No comments:

Post a Comment