Click on the headline to link to a "Wikipedia" entry for the great American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Book Review

This Side Of Paradise, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Simon& Schuster, New York, 1920

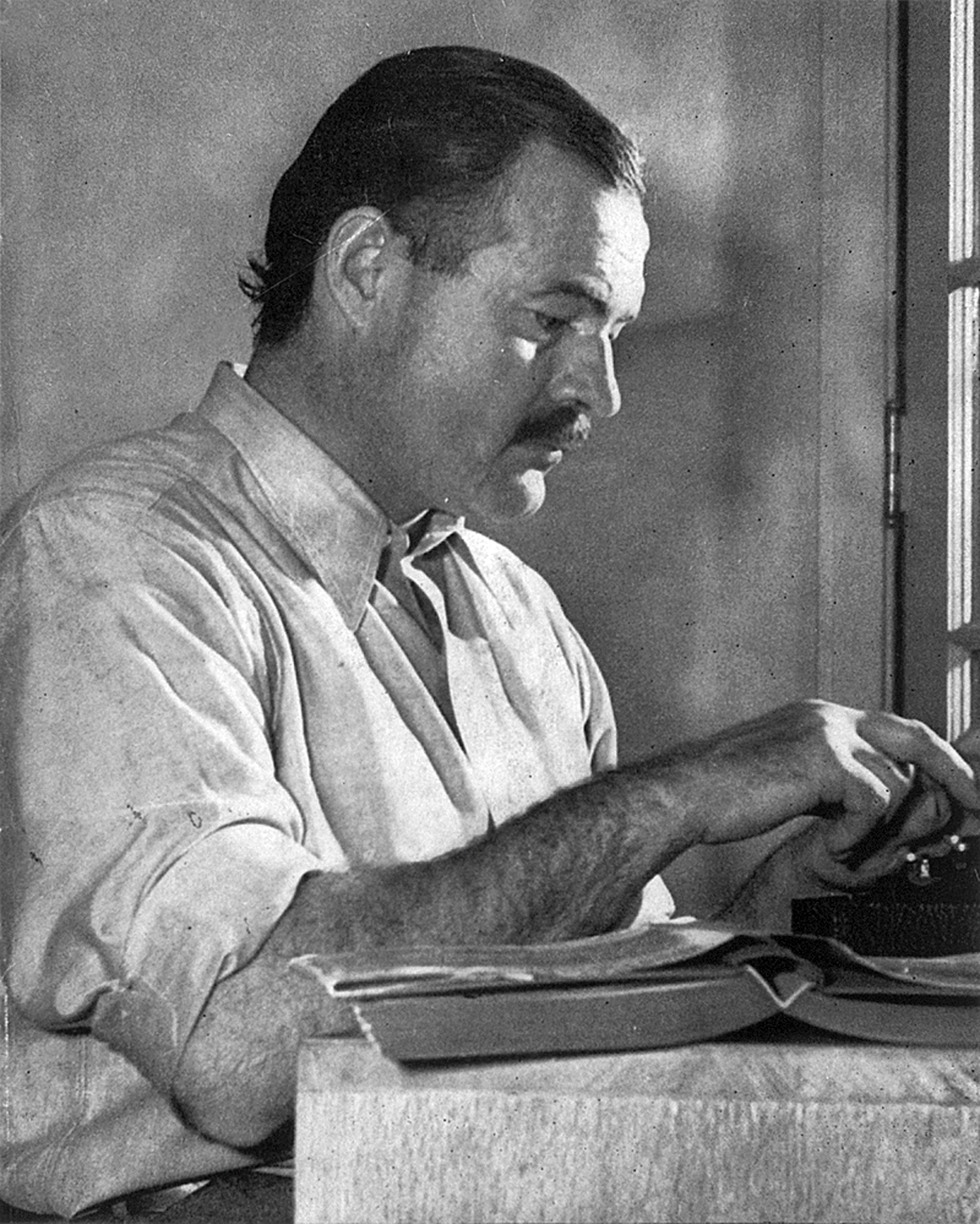

There was a time when if I used the name of the 20th century American writer Ernest Hemingway it also almost always meant that name of the author under review, F. Scott Fitzgerald, would follow in the next breathe (and then John Dos Passos). At that time I placed Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises” and Fitzgerald “The Great Gatsby” pretty closely together as exemplars of strong, non-nonsense writing styles and sparse but meaningful dialogue, along with a great narrative. “Gatsby” still certainly holds up. I find though , especially after re-reading this Fitzgerald first effort that put his name high up on the post-World War I literary scene, “This Side of Paradise”, that Hemingway has won the literary “battle” for the number one spot as the premier writer of that period. Strangely that period, “The Jazz Age” of the 1920s, is known as such in great part due to this book and is forever associated with Fitzgerald’s name.

As is to be expected from a first novel this book is very great indebted to the bits and pieces of autobiographical sketches that hold it together. And, moreover, is driven by the college exploits of the main and most developed character, Amory Blaine, at Fitzgerald’s alma mater, Princeton. The long and short of the story line is a very self-conscious attempt by Blaine , including plenty of now seemingly obscure literary references, to find out the mysteries of the meaning of life as a writer. That premise does not work so well in the college milieu that dominates the first part of the book. After all, many college students from time immemorial, from elite colleges and public universities alike, has thrashed over those questions, some successfully, some not.

What really made this book important (aside from a glimpse of “Jazz Age” manners, mores, styles and ennui) is the second part, after college and after Blaine had done military service during World War I in France (although the details of this service are only sketchily drawn). World War I acted a great divide for many of the men, and it was mainly men in those days, who suffered through it. The straight line, as the story line here details, from college to one’s proper place in the upper echelons of society got derailed, and not solely in Blaine’s case. This dislocation is mainly drawn out here as a spiritual crisis for Blaine but it also evoked class, sexual relations (almost all turning sour, for one reason or another), and life style. This is the heart of the book and the heart of Blaine’s (and Fitzgerald’s) dilemma: how to resolve the moral crisis within oneself without upsetting the social applecart that allows the wherewithal for such introspection.

What does not work here and what in the end makes this an unsatisfying work is Blaine’s rather vague and sudden attachment to some form of socialism near the end of the book. Although revolution was in the air and the great revolutionary efforts in Europe, including the seminal Bolshevik revolution in Russia, were in full blast for most of the book one would not know that things like the American government-driven Palmer Raids "red scare”, the split in the left-wing socialist movement in reaction to the American entry into the war and support of the Russian revolution, and the establishment of the American Communist Party were taking place. Blaine’s socialism is of a rather diluted sort, one suspects. Still this is a great first effort and if for no other reason that the display of Fitzgerald's' skill with language is worth reading, and re-reading.

Book Review

This Side Of Paradise, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Simon& Schuster, New York, 1920

There was a time when if I used the name of the 20th century American writer Ernest Hemingway it also almost always meant that name of the author under review, F. Scott Fitzgerald, would follow in the next breathe (and then John Dos Passos). At that time I placed Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises” and Fitzgerald “The Great Gatsby” pretty closely together as exemplars of strong, non-nonsense writing styles and sparse but meaningful dialogue, along with a great narrative. “Gatsby” still certainly holds up. I find though , especially after re-reading this Fitzgerald first effort that put his name high up on the post-World War I literary scene, “This Side of Paradise”, that Hemingway has won the literary “battle” for the number one spot as the premier writer of that period. Strangely that period, “The Jazz Age” of the 1920s, is known as such in great part due to this book and is forever associated with Fitzgerald’s name.

As is to be expected from a first novel this book is very great indebted to the bits and pieces of autobiographical sketches that hold it together. And, moreover, is driven by the college exploits of the main and most developed character, Amory Blaine, at Fitzgerald’s alma mater, Princeton. The long and short of the story line is a very self-conscious attempt by Blaine , including plenty of now seemingly obscure literary references, to find out the mysteries of the meaning of life as a writer. That premise does not work so well in the college milieu that dominates the first part of the book. After all, many college students from time immemorial, from elite colleges and public universities alike, has thrashed over those questions, some successfully, some not.

What really made this book important (aside from a glimpse of “Jazz Age” manners, mores, styles and ennui) is the second part, after college and after Blaine had done military service during World War I in France (although the details of this service are only sketchily drawn). World War I acted a great divide for many of the men, and it was mainly men in those days, who suffered through it. The straight line, as the story line here details, from college to one’s proper place in the upper echelons of society got derailed, and not solely in Blaine’s case. This dislocation is mainly drawn out here as a spiritual crisis for Blaine but it also evoked class, sexual relations (almost all turning sour, for one reason or another), and life style. This is the heart of the book and the heart of Blaine’s (and Fitzgerald’s) dilemma: how to resolve the moral crisis within oneself without upsetting the social applecart that allows the wherewithal for such introspection.

What does not work here and what in the end makes this an unsatisfying work is Blaine’s rather vague and sudden attachment to some form of socialism near the end of the book. Although revolution was in the air and the great revolutionary efforts in Europe, including the seminal Bolshevik revolution in Russia, were in full blast for most of the book one would not know that things like the American government-driven Palmer Raids "red scare”, the split in the left-wing socialist movement in reaction to the American entry into the war and support of the Russian revolution, and the establishment of the American Communist Party were taking place. Blaine’s socialism is of a rather diluted sort, one suspects. Still this is a great first effort and if for no other reason that the display of Fitzgerald's' skill with language is worth reading, and re-reading.